Product Overview

You will quickly review the step-by-step process to build a plan based on deep research into your customer, competitor, market, technology and capital.

We'd Love to Keep in Touch

Grow faster: Please provide your email to download free educational resources and receive product updates.

In this training, you will

- Walk through a brief overview of HowDo's research-based planning process.

Skills that will be explored

The United States has no shortage of resources. The nation’s assets have ensured that the country has had the largest economy in terms of GDP since 1971. So, how can it be that the United States also has the highest levels of poverty than any other industrialized nation? Because the wealthy are pursuing a business agenda that benefits themselves.

That’s why the country with many of the highest valued companies in the world— Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft— which represent close to six trillion dollars worth of businesses, has the highest income inequality of all the G7 nations, according to data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Our corporations are so well off that the CEO pay ratio in the United States—how much a CEO is paid compared to the average worker in the same company—is 10 times larger than any other developed country. The CEO pay ratio is over 400 to one in the United States while it is between 12 and 22 to one in countries such as Germany or the United Kingdom.

While CEOs are raking it in, many U.S. corporations do not provide even the most basic needs for its workers, such as healthcare, paid time off, retirement benefits or family leave, all of which are taken for granted by workers in other G7 nations.

Larry J. Merlo, CEO of CVS Health Corporation has a total income of close to $23 million while the median annual pay of a CVS worker is $27,900, giving a ratio of 434:1. Leslie Moonves, CEO of CBS Corporation, has a total income of $56 million while the average CBS worker earns $60,000, giving a ratio of 395:1, according to PayScale.

This is economic inequality at the extreme, and the gap between the upper income and middle and lower-income households is only widening.

I believe in the American Dream, but it’s one where every segment of the population – not just the wealthy – have opportunity, access to justice, freedom, life, liberty, and can pursue happiness.

I sound like I am railing against capitalism. But that’s far from the truth. In fact, I believe that capitalism can contribute to a dynamic evolving business community. I believe that there is a much better way for corporate America to function, so that long-term growth benefits everyone. I believe that corporate and entrepreneurial growth can reduce the widening economic gap. I also believe that right now, capitalism is broken, and while other countries are not exempt from propitious, if not abusive corporate practices, the United States is a serial perpetrator, and it is time we change our practices..

Let me be clear. I am not saying that this is about politics or government. Our current system, no matter who occupies the Whitehouse or controls the House and the Senate, is failing to provide equal opportunity, equal access to justice, freedom, life, liberty, and the ability for all to pursue happiness. Instead, our current system is exacerbating inequality, systematically destroying the environment, and taking our lives because of it. That’s because there is another power at work that is mightier than our political institutions: business. And business is sick.

Before COVID-19, the majority of US companies were struggling to grow. With the onset of the pandemic, businesses are failing at a record rate. At this very same time, Wall Street is doing better than it ever has. That is the problem: Wall Street and Main Street disconnected a long time ago. Wall Street is now so complicated that average citizens don’t have access to the funds and products where real money is made.

So we have to use the tools that we have at our disposal: our knowledge, mindset and the data we find all around us. If we use these simple tools, we can take old companies and make them new again. We can build new products, services and platforms that provide quality jobs. We can revitalize the American economy and, in doing so, create more opportunity, equality, equity and access to justice, freedom, liberty and happiness. We can successfully spread this newfound foundation and culture beyond our borders to other countries through business – not war.

That is why I built HowDo – because I fundamentally believe in a better future for all humanity. But first, we have some clear and present problems that need to be addressed for everyone’s benefit.

The rest of this article is a quick overview of the issues the motivated me to start HowDo. Some may find the data in this deep dive ugly. But we cannot fix a problem if we cannot identify and measure the problem. Therefore, I am sharing what follows not as a complaint, but as a call to action.

It is by thoroughly and deeply understanding these problems that we will find a solution. I read this data frequently to remind myself of why it is so important that we innovate the shit out of business, right now.

OUR CURRENT SOCIOECONOMIC LANDSCAPE AND WHAT THE FUTURE HOLDS

From recent media coverage, you might think we’re living in the Age of the Startup. Disruptive entrepreneurialism and Silicon Valley startup culture are the major business trends of the 21st century, and nearly all Americans have had their lives affected, if not transformed, by the resulting innovative technology. But startups are more than hip Silicon Valley tech firms trying to invent the next killer app. Across the economy, startups — of all sizes and in all industries — have been in decline for 30 years. The middle class has also been in decline over that period.

These two things are related.

Power is being centralized in huge businesses. Jobs are being lost to artificial intelligence and automation. Rapid technological improvement is accelerating these forces, leaving people with a shared feeling — of uncertainty.

New businesses and a thriving middle class are key ingredients of a strong job market. As we move toward the future, we need to understand the relationship between business creation, job growth, economic equality, innovation, and entrepreneurship.

The State of American Businesses

We’re Witnessing a Disturbing Trend in the Decline of New U.S. Businesses.

The 2017 Kauffman Index of Startup Activity finds that “startup activity remains in a long-term decline when compared to activity levels in the 1980s.” Citing Kauffman Foundation and U.S. Census Bureau data, Inc. editor Leigh Buchanan writes, “The number of companies less than a year old had declined as a share of all businesses by nearly 44 percent between 1978 and 2012.”

In FiveThirtyEight, Ben Casselman notes that, according to the Census Bureau, “Americans started 27 percent fewer businesses in 2011 than they did five years earlier. … As a share of all companies, startups have been declining for more than 30 years.”

Census Bureau data also suggests that “fast-growing startups [those that economists care most about due to their impact on increasing living standards or technological progress] are disappearing more quickly than slow-growing ones,” Casselman notes. “In 1982, 75 percent of all 5-year-old firms had fewer than 10 employees, while 12 percent had 20 or more. Two decades later, the share of new companies that stayed small had risen to 80 percent, while only 8 percent grew to 20 or more employees.”

In an article for the Atlantic, Jordan Weissmann makes an important point about terminology: “When most people hear the phrase ‘start-up,’ their minds immediately leap to small tech firms in Silicon Valley vying to become the next Facebook, Square, or Twitter. But those companies actually make up just a small, rarefied strata of new businesses — one which seems to be doing relatively fine.” Weissmann goes on to say, “It’s when we look at the full array of new companies, including what most of us just think of as small businesses in industries like construction or retail, that the problem becomes evident.”

“Only 12 percent of the Fortune 500 companies from 1955 are still in business, and last year alone, 26 percent fell off the list.” — Rewriting the rules for the digital age, Deloitte University Press, 2017

This trend is visible across industries. According to a 2014 Brookings Institution report, the decline in business dynamism and entrepreneurship have not “been isolated to particular industrial sectors and firm sizes.” Nor is this trend limited to a particular geography. Brookings Institution’s Ian Hathaway and Robert E. Litan point out that “the decline in entrepreneurship and business dynamism has been nearly universal geographically the last three decades — reaching all fifty states and all but a few metropolitan areas.”

The Declining Number of New Businesses Has Troubling Implications for the U.S. Economy and Labor Force.

Citing data from the United States Census Bureau’s Business Dynamics Statistics database, FiveThirtyEight’s Casselman writes, “New businesses are a key driver of job growth, responsible for more than 15 percent of new job creation despite accounting for just 2 percent of total employment.”

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Business Employment Dynamics data demonstrates that “the number of jobs created by establishments less than 1 year old has decreased from 4.1 million in 1994 … to 3 million in 2015. This trend combined with that of fewer new establishments overall indicates that the number of new jobs in each new establishment is declining.”

“The underlying worry is churn,” writes Inc.’s Leigh Buchanan. “In a dynamic economy, businesses are born, grow, and die; jobs are created and lost; and resources are reshuffled according to their best use. If there are fewer new companies and more aging ones, then labor and capital hang tight in old industries. The economy is not refreshed and growth slows.”

“When new businesses aren’t being born, the free enterprise system and jobs decline. And without a growing free enterprise system, without a growing entrepreneurial economy, there are no new good jobs. That means declining revenues and smaller salaries to tax, followed by declining aid for the elderly and poor and declining funding for the military, for education, for infrastructure — declining revenues for everything.” — Jim Clifton, American Entrepreneurship: Dead or Alive?, Jim Clifton, Gallup News, 2015

“We are behind in starting new firms per capita, and this is our single most serious economic problem,” writes Jim Clifton, chairman and CEO of Gallup. “I don’t want to sound like a doomsayer,” Clifton continues, “but when small and medium-sized businesses are dying faster than they’re being born, so is free enterprise. And when free enterprise dies, America dies with it.” Clifton cited U.S. Census Bureau statistics showing that 400,000 new businesses are born every year — but 470,000 die.

The problem goes beyond job creation. For years, the loss of workers’ welfare from depressed business creation was somewhat offset by the higher wages that came from comparable jobs at bigger companies. For the first time in decades, according to a recent study, this wage premium has disappeared.

The responsibility for these trends can’t fall solely on the Great Recession of 2007–09. Citing work from University of Maryland economist John Haltiwanger, the Atlantic’s Weissmann writes that the recession actually interrupted “the gradual mellowing of our job market.”

What does that “gradual mellowing” mean? A shrinking middle class — the very thing needed for a strong, growing economy.

The Declining Middle Class and Increasing Income Inequality

The United States Middle Class Is in Decline.

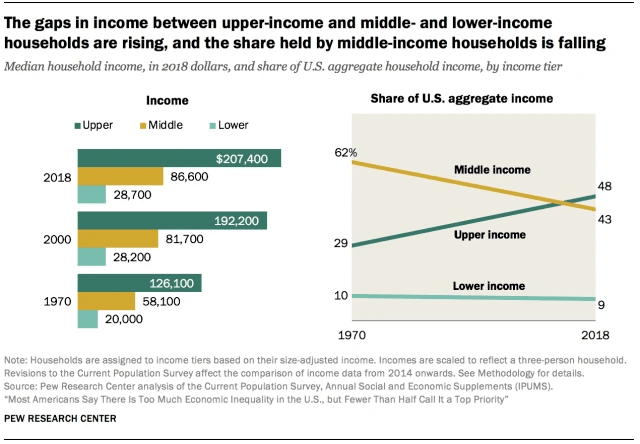

Source: The Elephant Chart in the EU Room , Harvard University Press Blog, 2016

It started as a chart hidden in a World Bank working paper. Now it’s become widely known as the “elephant chart” or “elephant graph.” It tracks growth in real income from 1988 to 2008 across the global income spectrum. At first glance, it looks like great news for the middle class, and globally speaking, it is. But pay attention to that dip that forms the base of the elephant’s trunk, around the 80th percentile.

That group that’s experienced almost no income growth? That’s where you’ll find the American lower and middle classes, who are relatively rich when placed on a global scale. Clearly, households in the 75th to 85th percentile of income distribution — “basically poor people in rich countries,” as Kaila Colbin describes them in NewCo Shift — have not done well. These people, according to the Economist, “seemed scarcely better off in 2008 than they had been 20 years before.”

The chart’s creator, Branko Milanovic, said in a PBS interview that it shows how the lower and middle classes in the United States and other rich countries, such as Japan and Germany, have struggled. He also pointed out another important point found at the far right edge of the chart: “The top 1 percent in the rich countries have done well.”

The chart has its critics. The Economist points out, for example, that the people in any income bracket in 1988 and 2008 might not be the same people. The 75th to 80th percentiles were dominated by “better-off Latin Americans and Westerners of modest means” in 1988, but by 2008 they had been joined by rich Chinese. How any bracket fared may not reflect how individuals did.

But Milanovic and his co-author, Christoph Lakner, accounted for this problem in their research, and other charts that illustrate how each income group fared over the 20-year period were less dramatic, but, the Economist admits, “recognisably elephantine.”

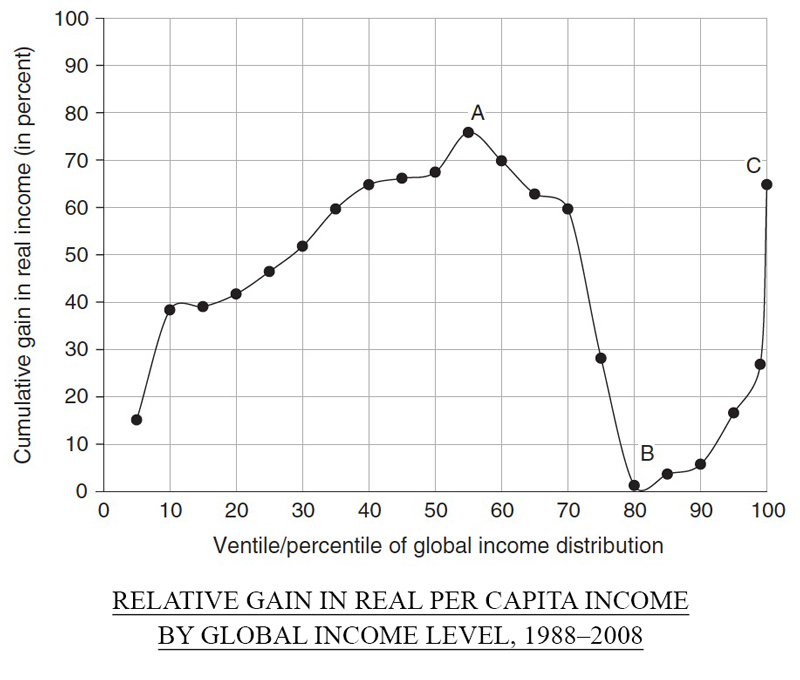

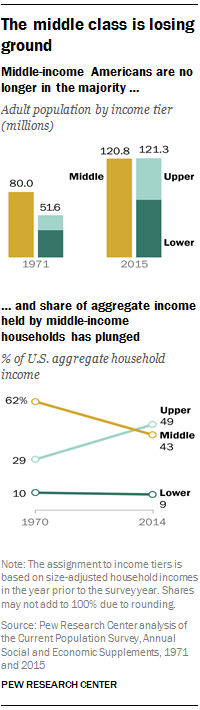

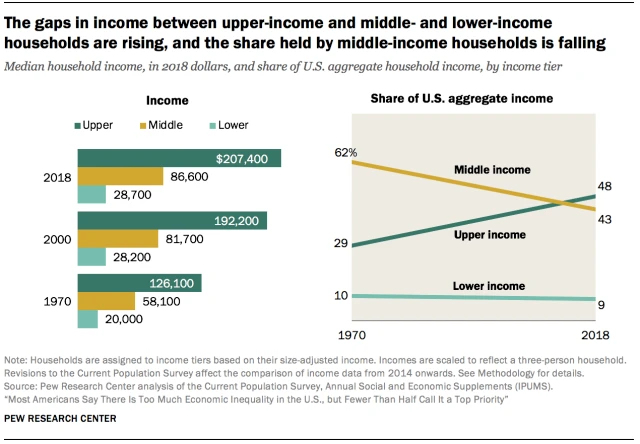

The Pew Research Center provides the bottom line: “After more than four decades of serving as the nation’s economic majority, the American middle class is now matched in number by those in the economic tiers above and below it.” Further, “In 2014, the median income of these households was 4% less than in 2000.”

But the problem goes beyond the shrinking of the middle class.

The Divide Between Upper-Income Families and Lower-Income Families Is Increasing.

A related phenomenon is the growing divide between the people on either end of the income and wealth spectra. It’s not quite true that the rich are getting richer and the poor are getting poorer. But it is the case that the rich are getting a lot richer, and the poor are mostly staying where they are.

A central takeaway from a 2014 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) working paper is that “In most OECD countries, the gap between rich and poor is at its highest level [in] 30 years.” This inequality trend is not “peculiar to America, but the trend is most visible there,” the Economist wrote in 2015. “This is partly because the gap between rich and poor is bigger than anywhere else in the rich world.”

In 2014, entrepreneur and venture capitalist Nick Hanauer wrote a “memo” in Politico, To My Fellow Filthy Rich Americans: The Pitchforks Are Coming. “Inequality is at historically high levels and getting worse every day,” he wrote. Using data from the Tax Foundation, Hanauer wrote, “In 1980, the top 1 percent controlled about 8 percent of U.S. national income. The bottom 50 percent shared about 18 percent. Today the top 1 percent share about 20 percent; the bottom 50 percent, just 12 percent.”

The previously mentioned Pew Research Center findings illuminate the extent to which upper-income families are gathering an increasing share of wealth:

- The nation’s aggregate household income has substantially shifted from middle-income to upper-income households, driven by the growing size of the upper-income tier. … Fully 49% of U.S. aggregate income went to upper-income households in 2014, up from 29% in 1970.

- In 1983, “Upper-income families … had three times as much wealth as middle-income families,” and “by 2013, they had seven times as much wealth as middle-income families.”

NewCo Shift’s Colbin puts it this way: “If you were rich to begin with, you’ve gotten richer — your income’s gone up by more than 60%” from 1988 to 2008.

The Circumstances and Absence of Opportunities That Inequality Creates Are Both Reinforcing and Intergenerational.

According to a RAND Corporation assessment of income inequality and intergenerational transmission of income, “Inequality of income and inequality of opportunity are correlated across countries, and this correlation could be driven by a variety of factors. In particular, greater disparities in income translate into greater disparities in families’ capacity to invest in their children’s human capital.”

“Far more than in previous generations,” the Economist reports, “clever, successful men marry clever, successful women.” This “‘assortative mating’ increases inequality by 25% … since two-degree households typically enjoy two large incomes.”

In the Atlantic, Alec Macgillis and ProPublica suggested in 2016 that in many heartland American towns, “The most painful comparison is not with supposedly ascendant minorities — it’s with the fortunes of one’s own parents or, by now, grandparents.”

Similarly, a 2013 Pew Research Center study found that Americans have “somewhat conflicted views about the economic prospects for the next generation. When asked about the future prospects of ‘children today,'” almost two out of three Americans “said that when today’s kids grow up, they would be worse off financially than their parents.” Additional Pew Research from 2016 shows that this is no idle fear: “In 2014, for the first time in more than 130 years, adults ages 18 to 34 were slightly more likely to be living in their parents’ home than they were to be living with a spouse or partner in their own household.”

Part of this trend away from moving out has to do with demographic changes, as young people have been marrying later and less often. But “trends in both employment status and wages have likely contributed to the growing share of young adults who are living in the home of their parent(s),” Pew Research Center notes.

Again, because of media coverage of Silicon Valley and the startup culture and the innovations that affected the lives of nearly all Americans in the last quarter century, it’s a good bet that most people worrying about a limited financial future for the young aren’t aware that startups have been in decline over that time. What people are worried about when they fear for their kids’ financial future is the loss of existing jobs, in older industries. And they’re not wrong to worry.

The Way It Is

The United States has no shortage of resources. The nation’s assets have ensured that the country has had the largest economy in terms of GDP since 1971. So, how can it be that the United States also has the highest levels of poverty than any other industrialized nation?

How can it be that the country with many of the highest valued companies in the world— Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft— which represent close to six trillion dollars worth of businesses, has the highest income inequality of all the G7 nations, according to data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development?

Our corporations are so well off, it seems, that the CEO pay ratio in the United States—how much a CEO is paid compared to the average worker in the same company—is 10 times larger than any other developed country. The CEO pay ratio is over 400 to one in the United States while it is between 12 and 22 to one in countries such as Germany or the United Kingdom.

While CEOs are raking it in, many U.S. corporations do not provide even the most basic needs for its workers, such as healthcare, paid time off, or family leave, all of which are taken for granted by workers in other G7 nations.

Larry J. Merlo, CEO of CVS Health Corporation has a total income of close to $23 million while the median annual pay of a CVS worker is $27,900, giving a ratio of 434:1. Leslie Moonves, CEO of CBS Corporation, has a total income of $56 million while the average CBS worker earns $60,000, giving a ratio of 395:1, according to PayScale.

This is economic inequality at the extreme, and the gap between the upper income and middle and lower-income households is only widening.

I believe in the American Dream, but it’s one where every segment of the population – not just the wealthy – have opportunity, access to justice, freedom, life, liberty, and can pursue happiness.

I sound like I am railing against capitalism. But that’s far from the truth. In fact, I believe that capitalism can contribute to a dynamic evolving business community. I believe that there is a much better way for corporate America to function, so that long-term growth benefits everyone. I believe that corporate and entrepreneurial growth can reduce the widening economic gap. I also believe, however, that right now, capitalism is broken, and while other countries are not exempt from propitious, if not abusive corporate practices, the United States is a serial perpetrator, and it is time we change our practices..

Let me be clear. I am not saying that this is about politics or government. Our current system, no matter who occupies the Whitehouse or controls the House and the Senate, is failing to provide equal opportunity, equal access to justice, freedom, life, liberty, and the ability for all to pursue happiness. Instead, our current system is exacerbating inequality, systematically destroying the environment, and taking our lives because of it. That’s because there is another power at work that is mightier than our political institutions.

Before COVID-19, the majority of US companies were struggling to grow. With the onset of the pandemic, businesses are failing at a record rate. At this very same time, Wall Street is doing better than it ever has. That is the problem: Wall Street and Main Street disconnected a long time ago. Wall Street is now so complicated that average citizens don’t have access to the funds and products where real money is made.

So we have to use the tools that we have at our disposal: our knowledge, mindset and the data we find all around us. If we use these simple tools, we can take old companies and make them new again. We can build new products, services and platforms that provide quality jobs. We can revitalize the American economy and, in doing so, create more opportunity, equality, equity and access to justice, freedom, liberty and happiness. We can successfully spread this newfound foundation and culture beyond our borders to other countries through business – not war.

That is why I built HowDo – because I fundamentally believe in a better future for all humanity. But first, we have some clear and present problems that need to be addressed for everyone’s benefit.

The rest of this article is a quick overview of the issues the motivated me to start HowDo. Some may find the data in this deep dive ugly. But we cannot fix a problem if we cannot identify and measure the problem. Therefore, I am sharing what follows not as a complaint, but as a call to action.

It is by thoroughly and deeply understanding these problems that we will find a solution. I read this data frequently to remind myself of why it is so important that we innovate the shit out of business, right now.

THE EFFECTS OF INCREASED AUTOMATION AND ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

America’s Labor Force Will Change Dramatically — and Most People Are Unprepared.

Research conducted by McKinsey & Company found that less than 5 percent of occupations “are candidates for full automation. However, almost every occupation has partial automation potential,” and “about half of all the activities people are paid to do in the world’s workforce could potentially be automated by adapting currently demonstrated technologies. That amounts to almost $15 trillion in wages.”

Source: dunkermoteren, 2017

“The activities most susceptible to automation,” the McKinsey report notes, “are physical ones in highly structured and predictable environments, as well as data collection and processing. In the United States, these activities make up 51 percent of activities in the economy, accounting for almost $2.7 trillion in wages.”

In their study “The Future of Employment: How Susceptible Are Jobs to Computerization?,” Oxford researchers Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael A. Osborne estimate that “around 47 percent of total U.S. employment is in the high risk category … i.e. jobs we expect could be automated relatively soon, perhaps over the next decade or two.”

The jobs and industries that may be most affected, suggests Fast Company’s Michael Grothaus, include insurance underwriters and claims representatives, bank tellers and representatives, financial analysts, construction workers, inventory managers and stockists, farmers, taxi drivers, manufacturing workers, journalists and actors.

“One widely held belief that is certain to be challenged is the assumption that automation is primarily a threat to workers who have little education and lower-skill levels. That assumption emerges from the fact that such jobs tend to be routine and repetitive. Before you get too comfortable with that idea, however, consider just how fast the frontier is moving. At one time, a “routine” occupation would probably have implied standing on an assembly line. The reality today is far different. While lower-skill occupations will no doubt continue to be affected, a great many college-educated, white-collar workers are going to discover that their jobs, too, are squarely in the sights as software automation and predictive algorithms advance rapidly in capability.” — Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future, Martin Ford, 2015

It would be ideal if our educational system were preparing young people for this looming future in which the traditional ways of working will be so disrupted. But it’s not.

CURRENT STRUCTURES FOR EDUCATION AND TRAINING

Deficiencies in Education Start in Early Childhood and Continue Through All Ages.

Inequality is baked into American education from the first day of kindergarten.

According to the Economist, America’s “education system favors the well-off more than anywhere else in the rich world. Thanks to hyperlocal funding, America is one of only three advanced countries where the government spends more on schools in rich areas than in poor ones.”

Higher education is also slanted in favor of those with higher income. The Economist reports that America’s “university fees have risen 17 times as fast as median incomes since 1980 … and many universities offer ‘legacy’ preferences, favoring the children of alumni in admissions.”

The Pew Research Center’s analysis of government data shows that “those Americans without a college degree stand out as experiencing a substantial loss in economic status.”

“On the day they start kindergarten, children from families of low socioeconomic status are already more than a year behind the children of college graduates in their grasp of both reading and math,” writes Eduardo Porter in the New York Times, and “nine years later the achievement gap, on average, will have widened by somewhere from one-half to two-thirds.”

This gap is compounded by lack of access to STEM education. A recent report by the U.S. Commerce Department’s Economics and Statistics Administration illustrates that STEM occupations are growing at a faster pace than non-STEM ones. Yet the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights found that “Nationwide, only 50% of high schools offer calculus, and only 63% offer physics,” and that “between 10-25% of high schools do not offer more than one of the core courses in the typical sequence of high school math and science education — such as Algebra I and II, geometry, biology, and chemistry.”

Those who do have access to such classes are typically in wealthy suburban areas. “If you look at where we admit students who are going to have the most amazing careers you can imagine,” Andrew Moore, dean of Carnegie Mellon’s School of Computer Science, told the 2017 U.S. News STEM Solutions conference, “you can pretty much map that against a map of the suburbs of regions of the United States which are rich enough to have strong math and computer science programs.”

This pattern reinforces the homogeneity in the tech world. Joint research into trends in computer science education by Google and Gallup finds that black students have less access to computer science classes at school and that black and Hispanic students have less access to computers at home. Women and girls, meanwhile, are much less likely to be encouraged to pursue computer science than their male counterparts.

Kids are our next inventors and innovators. Failing to create the deepest possible talent pool by introducing these ideas to as many of them as possible at an early age is a disservice not only to the students but to everyone.

Education and policies aimed at improvements to education can be successful at bridging the divide. Based on its assessment of inequality and opportunity, the RAND Corporation found that “policies that increase education have the potential to reduce inequality among the receiving generation and have impacts on the beneficiaries’ children, including (1) improved income position of those receiving financial assistance, (2) increased earnings of those who achieve schooling, [and] (3) general equilibrium effect on returns to schooling.”

The Education System Is Slow to Respond to Developments in the Economy and Labor Market.

Beyond the inequality issues, American education has also failed to adapt to the changing needs of the economy and culture.

“We need to rethink our education system,” writes Harm Bandholz on the World Bank Jobs and Development Blog. “As robots and machines are capable of taking over a growing number of tasks, humans have to focus on their comparative advantages, including non-cognitive skills.”

In the Harvard Business Review, Julian Birkinshaw suggests, “Maybe it’s time to put a bit more emphasis on creativity and commercial savoir faire in our education system. … In education the school curriculum focuses on traditional subjects taught in traditional ways, and it pushes students into narrow specialties. Many entrepreneurs claim they succeed despite, not because of, their schooling.”

A key finding in a recent report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine was that as automation “continues to complement or substitute for many work tasks, workers will require skills that increasingly emphasize creativity, adaptability, and interpersonal skills over routine information processing and manual tasks. The education system will need to adapt to prepare individuals for the changing labor market.”

In collaboration with Elon University’s Imagining the Internet Center, Pew Research Center canvassed “technologists, scholars, practitioners, strategic thinkers, and education leaders” about new educational and training programs, asking whether they will emerge and be able to effectively train workers in the skills required for future jobs. Seventy percent of the 1,408 respondents said “yes.” Most of the 30 percent who said “no” believe generally that such teaching adaptation will be able to teach workers new skills at the scale necessary for them to keep up with technological change. And, according to Pew, “Some of the bleakest answers came from some of the most respected technology analysts.”

Of course, we should mention that not everyone is sounding the alarms. Jack Schneider, writing in the Atlantic, cautions that, although current practices in school curricula might not be ideal, “Americans should think twice before dissolving into panic over what is being taught in modern classrooms,” which, he argues, are not as stuck in the past as sometimes imagined.

EXCLUSIONARY AND DIVISIVE IDEOLOGIES

Dangerous Socioeconomic Trends Are Contributing to the Rise of Disturbing Ideologies.

“Rising inequality and slow productivity gains may be the main economic challenges of the [21st] century,” Bandholz writes in the World Bank’s Jobs and Development Blog.

The Pew Research Center points out that “a flurry of new research points to the potential of a larger middle class to provide the economic boost sought by many advanced economies.” But while a larger middle class may be just what the American economy needs, the middle class continues to decline, resulting in greater inequalities and fewer opportunities for lower-income families.

“A thriving middle class is the source of American prosperity, not a consequence of it,” Hanauer wrote in his “memo” to “fellow plutocrats.” He continued, “The middle class creates us rich people, not the other way around.” Hanauer’s sense of urgency around this issue is obvious:

“I have a message for my fellow filthy rich, for all of us who live in our gated bubble worlds: Wake up, people. It won’t last. If we don’t do something to fix the glaring inequities in this economy, the pitchforks are going to come for us. No society can sustain this kind of rising inequality. In fact, there is no example in human history where wealth accumulated like this and the pitchforks didn’t eventually come out. You show me a highly unequal society, and I will show you a police state. Or an uprising. There are no counterexamples. None. It’s not if, it’s when.” — The Pitchforks Are Coming … For Us Plutocrats, Nick Hanauer, Politico, 2014)

The Center for American Progress’ Report of the Commission on Inclusive Prosperity says at the very outset that “no society has ever succeeded without a large, prospering middle class that embraced the idea of progress.” In democratic systems failing to create circumstances in which citizens can provide a “decent standard of life for themselves and their families,” the report said, “the result is political alienation, a loss of social trust, and increasing conflict across the lines of race, class, and ethnicity.”

HEALTHCARE IS BROKEN

“Government policy and economic forces have combined to make corporations and the wealthy more powerful, and most workers and their families less powerful. These workers receive a smaller share of society’s resources than they once did and often have less control over their lives. Those lives are generally shorter and more likely to be affected by pollution and chronic health problems.”

This was a statement from David Leonhardt and Yaryna Serkez, who write for The New York Times, and it describes what we are currently witnessing with the outbreak of COVID-19.

Considering the current pandemic, healthcare is perhaps the greatest area where the United States has failed to provide the most basic needs to all of its citizens, and people are dying.

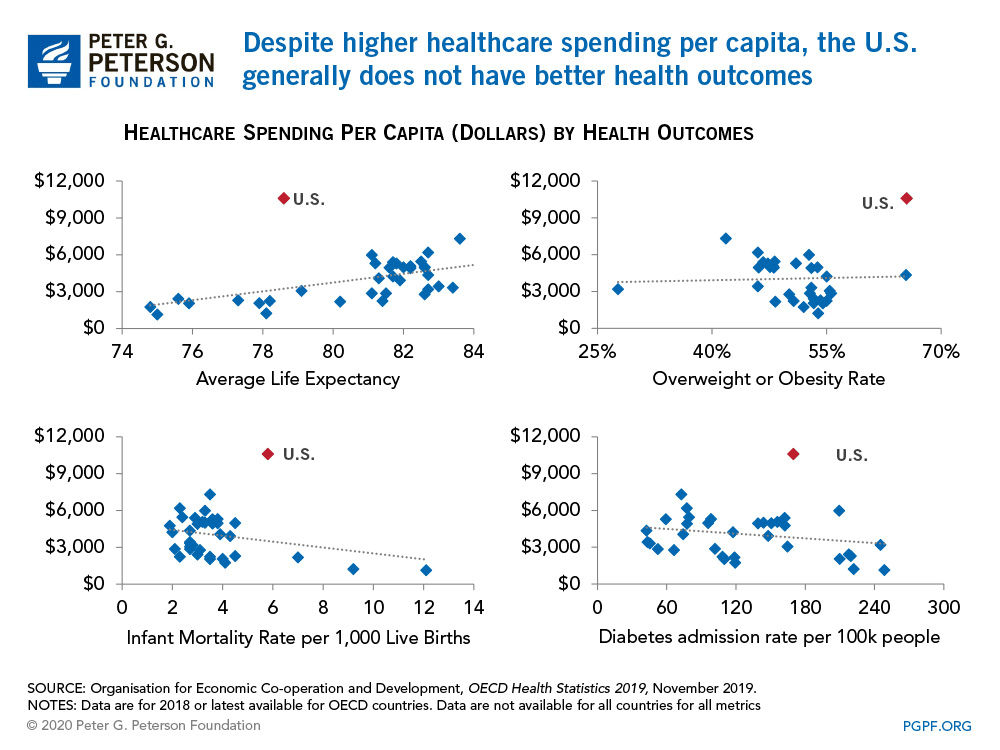

The United States, despite its vast resources and advanced technology, has one of the highest healthcare costs in the world. But, although outrageously more expensive, healthcare outcomes in the United States are worse than in most of the developed world.

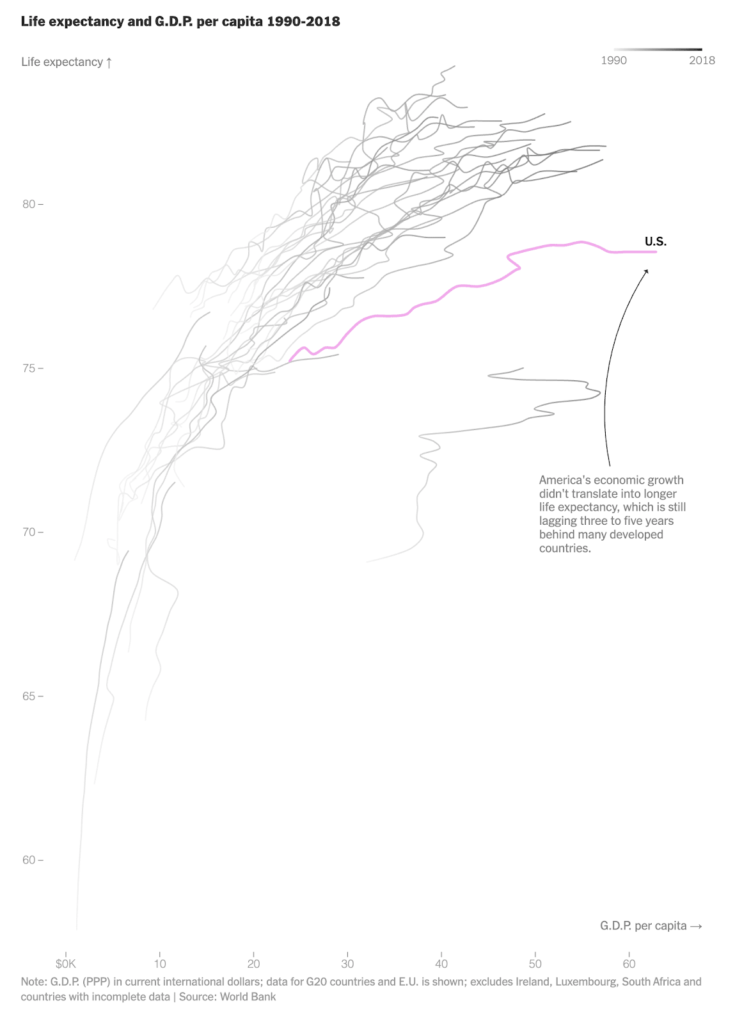

Even before the pandemic, life expectancy in the United States was no great shakes. It had only grown by three years since 1990. “There is no other developed country that has suffered such a stark slowdown in lifespans,” according to The New York Times.

High healthcare costs mean that the country is ill-equipped to face health crises such as COVID-19, and certain segments of the population are worse off than others falling victim more easily when a pandemic strikes. During the current pandemic, black and low-income communities are suffering higher morbidity rates than affluent communities.

USA Today quoted Dr. Thomas Frieden, a former director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Most epidemics are guided missiles attacking those who are poor, disenfranchised, and have underlying health problems, said Frieden.”

Dr. Otis Brawley, a professor at Johns Hopkins University, told USA Today, “the country has neglected to respond to warning signs that these communities―where people already live sicker and die younger than those in more affluent areas―could be devastated by a pandemic … This is a failure of American society to take care of the Americans who need help the most.”

Brawley states that “vulnerable counties are scattered throughout the country, but they are concentrated across the South, in a belt of deprivation stretching from coastal North Carolina to the Mexican border and deserts of the Southwest.”

It is perplexing that before the pandemic, 44 million people in the United States had no access to healthcare despite the vast amounts spent. In 2018, the United States spent approximately about $3.6 trillion on healthcare, which averaged around $11,000 per person, according to data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and cited by the Peter G. Peterson Foundation.

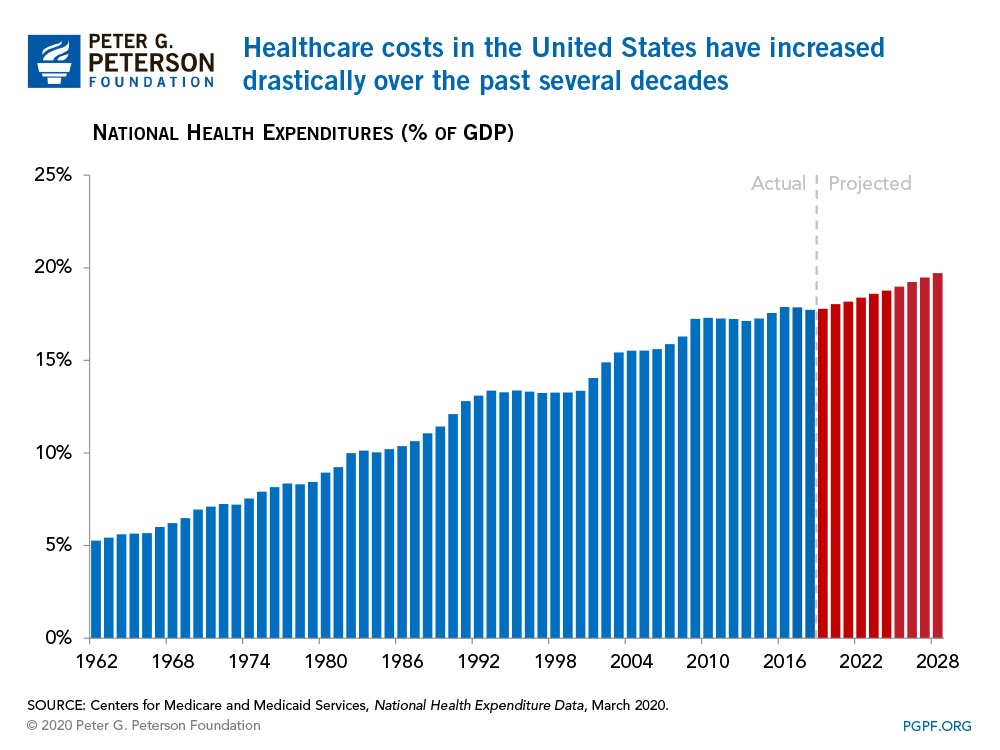

Healthcare costs, in terms of the share of GDP, have gone from 5 percent in 1960 to 18 percent in 2018. By 2020, the share is expected to be 20 percent of GDP, with a total of $6.2 trillion or $18,000 per person, and that is without considering the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic. But still the nation could not and cannot provide health coverage for all.

Some of the skyrocketing healthcare costs can be attributed to the aging population. Individuals aged 65 and over accounted for 16 percent of the population in 2018, but the age group will exceed 20 percent of the population by 2030.

As individuals turn 65, they become eligible for Medicare. Thus, the number of Medicare enrollees is expected to increase from 60 million in 2018 to 75 million by 2028. That expansion in enrollment is expected to double Medicare spending over the next 30 years relative to the size of the economy—growing from 3 percent of GDP in 2019 to 6 percent by 2049, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

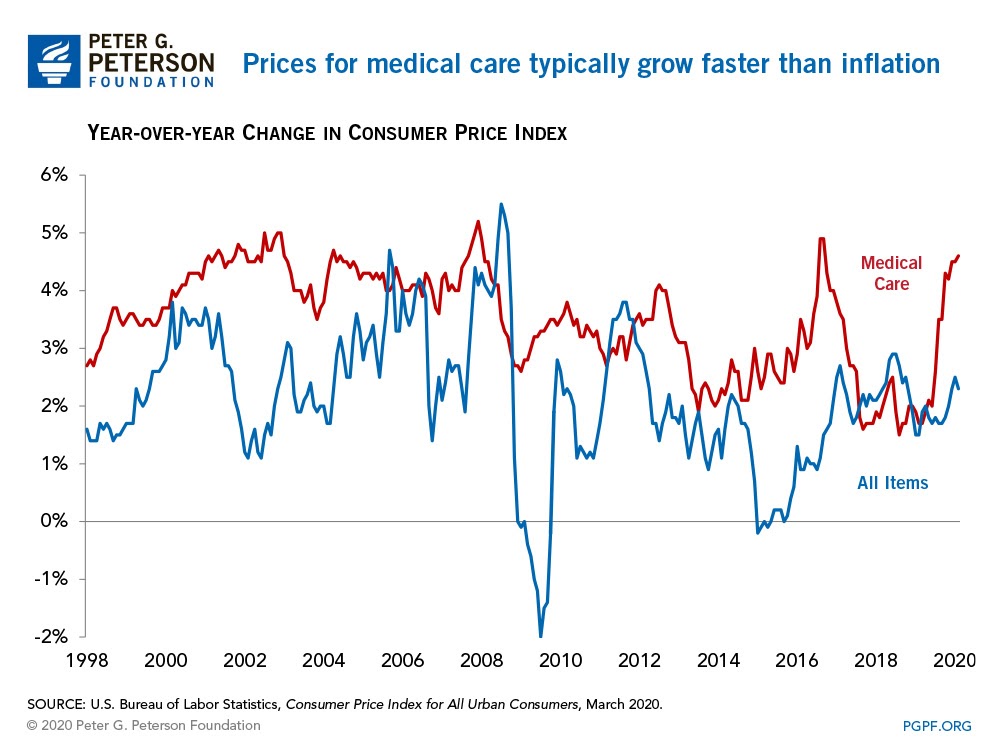

The price of healthcare has risen more quickly than any other good or service in the economy. In the past 20 years, the consumer price index (CPI)—the average change in prices paid by urban consumers for various goods and services—has grown annually at an average of 2.1 percent while the CPI for medical care has grown at an average rate of 3.5 percent per year.

Possible reasons for the high prices might be that new procedures and products are more expensive, there is administrative waste in the insurance and provider payment systems, and hospital consolidation can create a lack of competition or hospital monopolies allowing providers to increase prices.

But that really boils down to is corporate hospital monopolies setting high prices and disguising them with overly complex and wasteful insurance and provider payment systems.

We could wait until Congress passes health reform for things to improve, but governments don’t tend to take on the big players, and it could be decades before anything really changes. More importantly, I don’t think we have the luxury of time. There has to be change of a different kind.

CAPITALISM IS BROKEN

Fundamentally, whatever your political leanings, you have to admit that capitalism is broken, at least in this country. We are in a worse state than ever before with the exception of the Great Depression.

The COVID-19 crisis has brought our economy to a grinding halt partly because we have no resilience to shock. Unemployment is through the roof and reached 14.7 percent in April 2020. Consumer spending, which dramatically influences GDP, is expected to have dropped by 17 percent in the first two quarters of 2020.

Our economy is bottoming out, and so far, it is unclear how we will recover from the crisis. Dr. Baniel Bachman, senior manager at Deloitte, has predicted that it will be mid-2021 before we see even the beginnings of a recovery from the effects of COVID-19. The Congressional Budget Office, meanwhile, predicts that the pandemic will cost the U.S. almost $8 trillion in lost economic output this decade.

Even before this massive shock hit our shores, severe systemic economic problems were eating away at our core, weakening our immune systems, and making us vulnerable to threats.

As I said, this is beyond a political issue. We will always have some measure of inequality because, whatever political party is in power, there will always be an elite that is better off. Whether it is a financial elite, an educated elite, or a networked elite, the power always lies somewhere. Inequality has existed in this country since the colonials first took land from the native Indians, and it will always exist to some extent. Inequality is a virus that affects every country whatever the political structure because pure communism cannot, does not, and should not work.

However, some countries have struck a balance between outright corruption among the power elite and egalitarianism, if only temporarily. These countries have done so because of pressure applied by the masses. When workers unite, whether through unions or otherwise, they have the power to make changes.

In 2013, for example, legislation was passed in France whereby companies are obligated to have employee representatives at the board level. Worker representation is also prevalent in other E.U. countries such as Germany and The Netherlands.

During the current pandemic, a report by Stephen Greenhouse, writer for The Guardian, describes how workers have succeeded in clawing back some jobs by fighting for legislation to stop corporations using the pandemic as an opportunity to hire cheaper labor.

Greenhouse’s report describes how well-known hotels in cities such as Baltimore, Phoenix, and Boston dismissed employees and told them to reapply. If hired, the workers were told that they would have to start out as new employees with the associated lower salaries and perhaps no benefits.

My point is not that unions are the answer necessarily, but we have to change things from the ground up. We have to loosen Wall Street’s grasp around the nation’s neck because it is strangling long-term growth. We have an opportunity to rebuild the country’s businesses, and innovation is the path to sustainable growth. We need sufficient movement and momentum in the direction of business evolution, not a bull stock market.

If nothing else, I would like you to consider the following three points.

- The greatest threats to life are inequality and global warming (in the interests of time, I address global warming elsewhere in the HowDo content, see…).

- The greatest causes of inequality and global warming are corporations.

- The best way to change corporations is through innovation.

My goals in this article are, first, I want to convince you of the three points above; second, I want you to want to learn to innovate, and third, I will show you how to innovate, for free.

It is my belief that corporate America must change. It is my belief that it can, and that change will come from entrepreneurs who will build businesses differently. There is no reason this nation cannot nurture new concepts, experiment, fail, reiterate, and once again be the innovation leader that put a (hu)man on the moon and the iPhone in our hands.

PAY-TO-PLAY: WHO’S REALLY IN CONTROL?

There is plenty of blame to go round for our past complacency. Some blame the current government, some blame the past government, some blame certain races, sexes, religions, or whatever is in their line of sight. For me, I blame the CEOs and the C-suites who have perpetuated the great pyramid scheme that is Wall Street.

Now, governments could regulate corporations and influence them so that climate change is mitigated and inequality is reduced, but they don’t, and they won’t. In fact, the dynamic so far has been quite the opposite.

Instead of the government reigning in shady and corrupt corporate practices, companies pay off the government to represent their corporate interests and ignore their shenanigans. Political candidates are elected with corporate donations in a “pay-to-play” relationship, which they willingly engage in.

It all started in the 1970s when the Supreme Court authorized PACs and Super PACs and allowed corporations, unions, special interest groups, and individuals to spend unlimited amounts on political campaigns. The result has been that the candidate that raises the most money, wins the campaign. In return for those donations, and after winning, the candidate then does what they can to advance their donor interests and to ensure more ready funds for the next round of fundraising. So, whatever the political bent of the incumbent, it is in their interest that corporations do well, at least in the short term.

Business for American Promise is fighting for legislation to end unlimited political spending. According to the organization, elected officials now spend 30 to 70 percent of their time raising

money in races that cost 20 times more than they did in 2000. One CEO described the system as “legalized extortion.” According to the executive, “We are seeing every politician coming in here with their hand out, demanding contributions.”

The result of these schemes is that the real drivers of growth are rendered irrelevant. Pay-to-play politics corrupts democracy and destroys the integrity of the government.

Because rich donors and companies get candidates elected, the elected government makes sure they’re taken care of when it comes to paying taxes. That’s why companies don’t pay taxes, people pay taxes. Companies and rich donors get richer, and the tax-paying worker gets poorer.

The Fundamentals

It’s not all Easy Street for corporate American, however. The results of tactics used to stay afloat—buybacks to inflate stock prices, acquisitions, depleting human resources, off-shoring—are all short-lived. The airlines are a perfect example of this. The U.S. airline industry has spent 96 percent of free cash flow on buybacks over the last decade, according to Brandon Kochkodin of Bloomberg, leaving them with no capacity to weather the COVID shock.

At some point, a company has to create value over the long term to stay relevant. Many are not, and they are disappearing at an increasing rate.

A pre-COVID 2018 report by Innosight shows just how quickly the tenure of S&P 500 companies has been shortening. According to the report, the average tenure for companies was 33 years in 1964. The length of tenure decreased to 24 years by 2016 and is expected to be just 12 years by 2027. That means that over 50 percent of S&P 500 companies will be replaced in the next 10 years.

At the same time, society, at a certain point, will not tolerate widening inequality. There will be more disease, more pandemics, fewer educated workers, and increased civil unrest. Every person needs a certain level of income, health, housing, and education. People rightfully demand work environments that are diverse and safe. In a developed society, people want good jobs with good companies that allow them to live, save, and retire comfortably at a reasonable age. And this should not be such a big ask in the richest country in the world with over $60 trillion in private wealth.

“Good Companies” —Where American Corporations Are Falling Short

What is the definition of a “good company?” Is it one with strong and positive leadership? Is it one that values its employees and with a positive corporate culture? Is it one that provides excellent customer service? Is it one with a high market cap? The definition changes depending on your relationship with the company, but most would agree that in an advanced, industrialized society, some characteristics are fundamental.

A Livable Wage

U.S. households have suffered from a rising cost of living, student loan debt, credit cards, and unexpected medical expenses, but the greatest problem has been stagnant wages.

Even before the COVID-19 epidemic shut down the economy, many Americans were on the brink financially. A study by MagnifyMoney showed that 53% of respondents live paycheck-to-paycheck, meaning they have no money left after all expenses are paid. Seventy percent of respondents said that even one missed paycheck would cause bills to pile up. Nearly 44 percent of respondents would not be able to pay for their housing if they did not receive their next paycheck, and about one in four would have to miss a credit card payment. According to Bankrate’s latest Financial Security Index, over 10 percent do not have enough money to see them through one week without pay, and almost three in 10 adults have no emergency savings at all.

After the shutdowns because of Coronavirus, 47.2 percent of adult Americans now don’t even have jobs, and it would take 30 million new jobs for the country to get back to its peak employment levels, according to Torsten Slok, a chief economist with Deutsche Bank.

Reasonable Working Hours

Most European nations work five days a week and eight hours a day, which adds up to 40 hours a week, although some countries work a35-hour workweek (France, for example). You might think that it is the same in the United States, but it’s not. American workers do work eight hours a day, but a lunch break is not included. Therefore, if a worker takes 30 minutes or an hour for lunch, they must tack on that time. In many cases, employees work 45 hours a week but are paid for just 40.

So, what’s a few (around 250 to be precise) extra hours a year? Well, that’s not quite the full story. According to the New York Times citing federal data, over eight million Americans (5 percent) held more than one job in July 2019 because one full-time job was not enough to make ends meet.

According to the data, the daily work hours for multiple jobholders work out to be an average of 42.95 hours per five-day workweek, relative to 39.7 hours for single jobholders. Multiple jobholders, however, are also more likely to work on the weekends. Still, it’s alright, because only a “tiny fraction” (4 percent) actually work two full-time jobs, so that leaves only eight million Americans working an 80-hour week, weekends not included.

Paid Time Off (Vacation Time)

The United States is the only advanced economy that doesn’t guarantee paid vacation and one of only 13 countries in the world not to do so, according to the World Policy Analysis Center at the University of California Los Angeles. For paid time off, the United States is comparable with the developing nations India, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sierra Leone. European nations, meanwhile, mandate a few weeks off a year. French workers, for example, receive 30 paid vacation days a year, and Scandinavian workers get 25 paid days off.

And it is even more unfair than that. In the United States, low-wage earners disproportionately work without paid vacation. Only 49 percent of those in the bottom fourth of earners get paid time off, compared with 90 percent among the top quarter of earners, according to The Center for Economic Policy and Research.

According to John Schmitt, Vice President of the Economic Policy Institute, “Relying on businesses to voluntarily provide paid leave just hasn’t worked. It’s a national embarrassment that 28 million Americans don’t get any paid vacation or paid holidays.”

Healthcare

American workers are between a rock and a hard place where healthcare and work is concerned. Many rely on their employer for healthcare and are forced to accept dire work conditions, particularly at times of high unemployment. As far as innovation is concerned, tying healthcare to an employer stifles entrepreneurialism. For many individuals who may want to leave a job and go it alone, the prospect of paying for healthcare for a family can be overwhelming and often prohibitive. According to the ACA Marketplace, the average premium for healthcare for families without Obamacare subsidies is $1,021 with a deductible of $8,352. Many more people do not have healthcare even if they are loyal to an employer.

European countries, on the other hand, offer free government healthcare as well as private options. In the United States, there is no government-funded healthcare for workers, and employers are not required to provide you with health insurance.

Small businesses are finding it hard to meet the cost of medical plans for their employees and, according to Paycore, an HR software provider, 46 percent are trying to cut costs by offering lower-cost plans with high deductibles. According to Vivian S. Lee, writing for the Harvard Business Review,

“Before Covid-19, premiums for employer-sponsored plans had been consistently outpacing inflation. In 2019, the Kaiser Family Foundation reported that the average annual premium for employer-sponsored health insurance was a whopping $20,576 for a family of four (and $7,188 for an individual)—a 54 percent increase over the previous 10 years. That dwarfs the average inflation-adjusted increase of 4 percent in wages in the same 10-year period from 2009 to 2019.”

Retirement

Most EU countries provide pensions as long as you have worked the required number of years. Not so in the United States. American workers are responsible for saving for their own retirement. Some employers offer a 401k plan (multiple stock portfolio managed by a bank or private financial company), but it is not a requirement, and if the stock market plummets, a retiree may find their portfolio has vanished. A 2019 study by Northwestern Mutual found that 15 percent of Americans have no retirement savings at all, and that was pre-COVID-19.

In some cases, according to Andrew G. Biggs for MarketWatch, it might be better for low-income earners to not save at all for retirement because doing so might cut them out of social security. Congressional Budget Office figures show that a low-earning worker retiring today receives a Social Security benefit equal to approximately 84 percent of their career-average earnings while better-off workers receive “replacement rates” of only 43 percent.

According to Biggs, retirement plans and social security are not meant to increase your standard of living when you retire, they are designed only to maintain it. However, some at the poverty level actually do see their standards of living increase when they receive Social Security. If that’s not a sad social commentary, I don’t know what is.

At the most base level, a livable wage, paid time off, healthcare, and retirement are all things that a human being needs. They should not be negotiable in the wealthiest economy in the world.

At the other end of the spectrum, the C-suite elites are doing rather well where healthcare and retirement coffers are concerned. Does that mean that the innovation and growth strategies of companies are paying off? While we are touching on inequality, what about workplace diversity, for example? Are the benefits of the country’s diverse workforce reflected in corporate America? More to the point, is the nation’s heterogeneous populace fairly represented in corporate America?

Diversity

In the face of overwhelming public pressure, CEOs are finally using their power to talk about diversity, but that’s part of the problem. Lots of talk, and no action. Just how diverse is the average executive suite? What groups are represented on boards other than old white men? How many CEOs are not life-long members of the “old boys club?” How many are members of the LBGQT+ community? How many are hispanic or black women?

In 2020, there are only four black CEOs leading Fortune 500 firms, and fewer than 10 percent of the most senior P&L leaders in the Fortune 500 were black. In fact, since 1955, there have only been 15 Fortune 500 black CEOs, according to the media platform Chief Executive.

On the brighter side, the number of women running America’s largest corporations has hit an all-time high. Thirty-seven of the companies on this year’s Fortune 500 are led by female CEOs, according to Fortune. That’s a whopping 7.4 percent. And, wait for it, there are four openly LGBTQIA+ CEOs in the Fortune 500. At least, that’s a start.

Ceo Pay

Over the past 35 years, corporate America has exceeded its wildest expectations where CEO compensation is concerned. CEOs in the United States have no intention of falling prey to the brain drain and off-shoring to summer climes where the living is easy. Here’s why.

Average CEO compensation has rocketed so fast that in 2009, according to Cydney Posner of Cooley, an international law firm, Senator Durbin saw the need to introduce S1006, the Excessive Pay Shareholder Approval Act. The bill prohibited a public company from paying annual compensation to an employee in an amount that exceeds 100 times the average compensation paid to all employees of that company without a 60 percent supermajority vote of the shareholders.

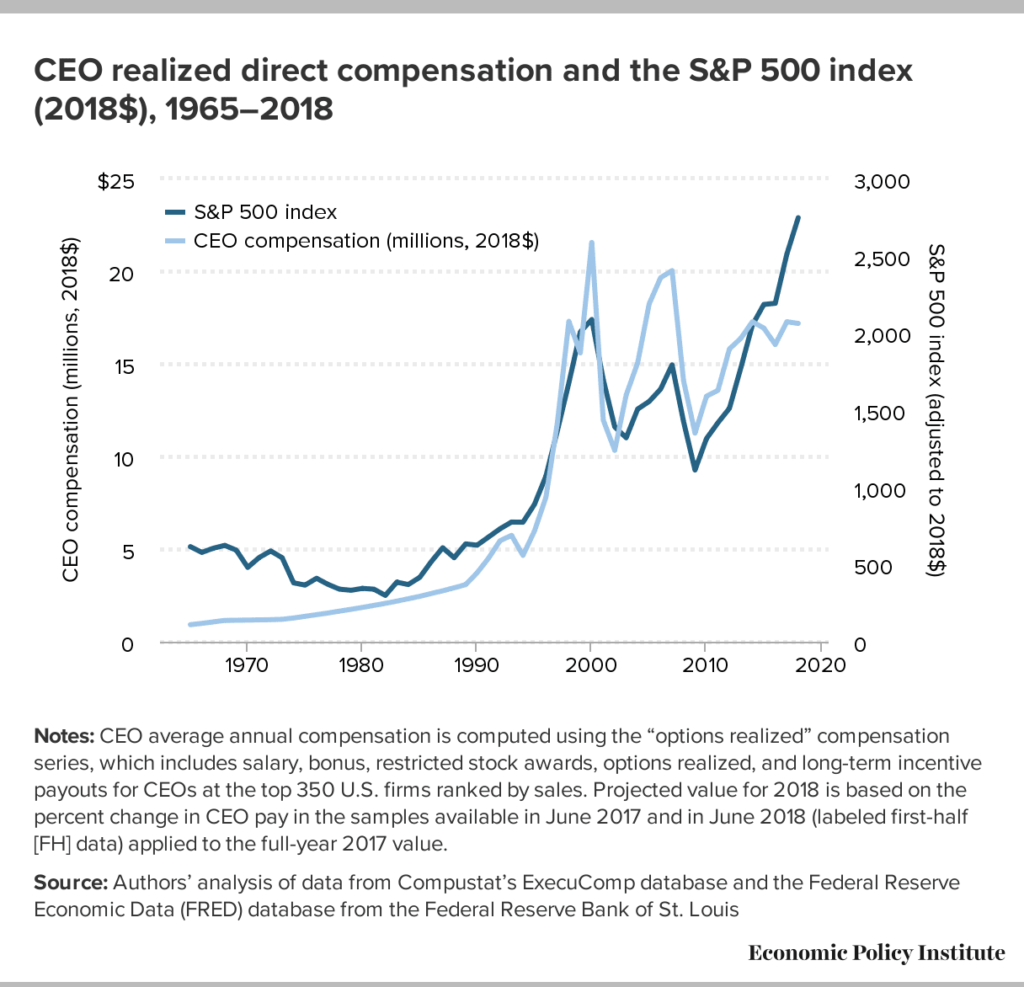

Durbin cited statistics from the Economic Policy Institute indicating that, in 1965, U.S. CEOs at major companies made 24 times the pay of an average worker. By 2005, CEOs earned 262 times the pay of an average worker.

To give some global context to those numbers, U.S. CEOs earn from 400 to 500 times the median salary for workers, which is ridiculous when you consider that in the United Kingdom, the ratio is 22; in France, it is 15; and in Germany, it is 12, according to Steve McDonnell of Chron.com.

In 2015, Congress passed a law requiring publicly traded companies to report their employees’ median pay compared to the CEO’s pay in the vain hope that transparency might make a difference.

It hasn’t, and you can see the CEO Pay Ratio for S&P 1500 and Russell 3000 companies with The Farient Pay Ratio Tracker™ https://farient.com/insights/pay-ratio-tracker/. I recommend you read this sitting down.

A long-running study by the AFL-CIO shows leaders of S&P 500 companies made about 347 times more than their average employees in 2016, up from 41 to 1 in 1983, and a 2018 survey by Equilar Inc. found that CEOs earned 140 times more than their median workers.

More recently, and if you fancy a giggle, the Economic Policy Institute published compensation growth rates from 1978 to 2018. The data show that the typical worker’s growth rate for that period was 11.9 percent; for very high earners the growth rate was 339.2 percent; but for CEOs, the growth rate was 1,007.5 percent.

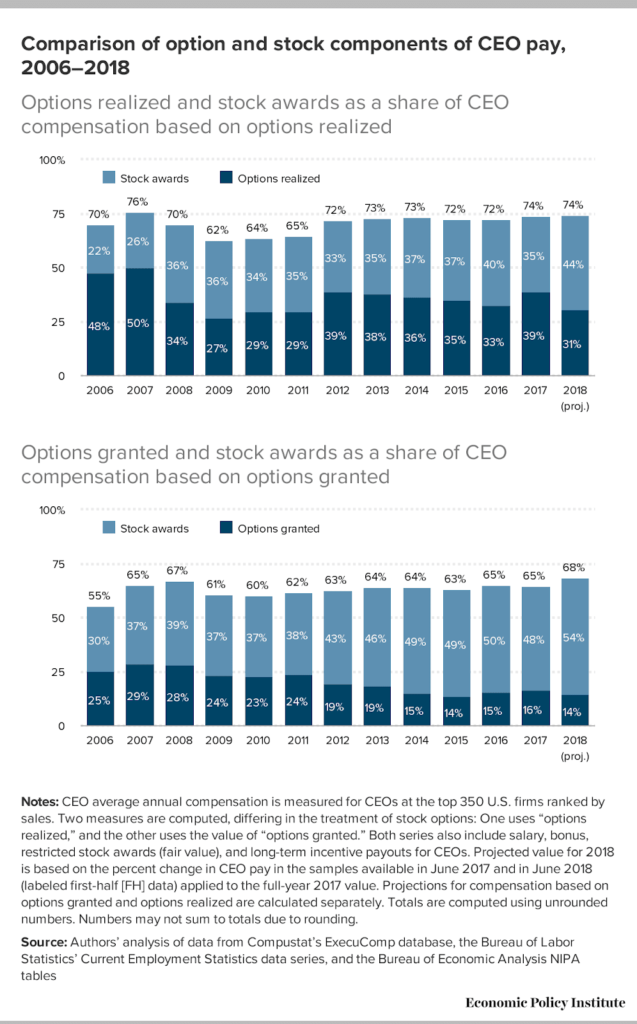

Lastly, by some inconceivable market dynamic, CEO pay has trended remarkably in line with the S&P 500.

How is it possible that CEO compensation could mirror the stock market when stocks go up and down and even disappear? Are America’s CEOs really that good? Do they have super-power foresight, amazing skills in long-term planning, or bleeding edge AI engineering applied to their growth strategies? Hardly, stock buybacks will do the trick.

Stock Buybacks = Trickle Up

“High school graduates used to be able to make a comfortable living. The disappearance of “In the days before a buyback announcement, executives trade in relatively small amounts—less than $100,000 worth. But during the eight days following a buyback announcement, executives on average sell more than $500,000 worth of stock each day—a fivefold increase. Thus, executives personally capture the benefit of the short-term stock-price pop created by the buyback announcement.'”

— Commissioner Robert J. Jackson, Jr. U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

Corporate America has aced the art of stock buybacks. As well as being the source of short-term price boosts, guaranteed stock returns, and CEO bonuses, stock buybacks have become America’s institutionalized inequality generator.

Let’s start by explaining the purpose of stock buybacks. When a company has cash on hand, it can choose to spend it in many ways. Some examples are re-investing in the company with R&D initiatives, building talent and human resources, strategically acquiring assets or other companies, or paying down debt. Last but not least, a company with cash on hand can also buy back stock.

In doing so, very often, a buyback signals to investors that the C-suite is confident that it’s stock will go up in the not too distant future because of its sound growth strategy. If the company also succeeds in meeting quarterly earnings expectations and satisfying Wall Street analysts, investors will be convinced, and the stock price will go up due to increasing demand.

So, where does the CEO fit into this picture exactly. Unfortunately, most CEOs of public companies are puppets. They are hand-picked by boards to do their bidding, which is making Wall Street money by meeting quarterly earnings calls, boosting the stock price, and ensuring dividends for shareowners.

The worrying implication of this codependency is that the market is inflated, or at least falsely kept afloat. From 2014 to and 2018, Goldman Sachs S&P 500 companies spent close to $3 trillion buying their own stock back. According to Goldman Sachs, the next five largest purchasers of stock—households, mutual funds, pension funds, life insurance, and foreign investors, cumulatively sold $1.1 trillion. That means that the “growth” the S&P 500 experienced between 2014 – 2018 was exclusively funded by companies buying their own stock back. This is not growth…

Thus, other than companies buying their own stock back, there is almost no demand in the market for the stock. Even Goldman Sachs stated, “Repurchases have consistently been the largest source of U.S. equity demand…Without company buybacks, demand for shares would fall dramatically.” This is because few segments of society other than high earners can afford to invest in the markets beyond a paltry retirement plan.

The following are some insights from experts on the subject of buybacks.

Robert J. Jackson, Jr. was appointed by President Donald J. Trump to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and served as Commissioner from January 11, 2018, to February 14, 2020.

Commissioner Jackson advocated investor protection, capital market transparency, and revised insider-trading law. A research paper by Jackson, Cohen, and Mitts, called “The 8-K Trading Gap,” prompted legislation to stop executives from trading before the public announcement of key events. Jackson also testified before Congress on the political influence public companies wield by spending shareholder money on politics, how large investors help to keep that spending hidden, and drew attention to the non-standard accounting measures used to boost CEO pay.

One of Commissioner Jackson’s speeches explained how executives use buybacks to cash out their personal holdings of company stock. Jackson believed that companies that allow CEOs to sell into buybacks underperform in the long run.

Here is part of that speech.

“High school graduates used to be able to make Now, we all know what happened the last time a Republican-controlled government pushed through a corporate tax holiday in 2004. As that bill’s sponsors hoped, American companies repatriated billions of dollars of overseas cash. But corporations didn’t invest most of that money in innovation. They didn’t invest it in retraining their workforce or raising wages. Instead, executives largely used the influx of fresh funds for massive stock buybacks.

… when I first took this job, I worried that 14 years later history would repeat itself, and the tax bill would cause managers to focus on financial engineering rather than long-term value creation. Sure enough, in the first quarter of 2018 alone American corporations bought back a record $178 billion in stock. On too many occasions, companies doing buybacks have failed to make the long-term investments in innovation or their workforce that our economy so badly needs. And, because we at the SEC have not reviewed our rules governing stock buybacks in over a decade, I worry whether these rules can protect investors, workers, and communities from the torrent of corporate trading dominating today’s markets.

What did surprise us, however, was how commonplace it is for executives to use buybacks as a chance to cash out. In half of the buybacks we studied, at least one executive sold shares in the month following the buyback announcement. In fact, twice as many companies have insiders selling in the eight days after a buyback announcement as sell on an ordinary day. So right after the company tells the market that the stock is cheap, executives overwhelmingly decide to sell.

And, in the process, executives take a lot of cash off the table. On average, in the days before a buyback announcement, executives trade in relatively small amounts—less than $100,000 worth. But during the eight days following a buyback announcement, executives on average sell more than $500,000 worth of stock each day—a fivefold increase. Thus, executives personally capture the benefit of the short-term stock-price pop created by the buyback announcement.

Other finance experts have spoken out on the buyback game and why distributing cash to shareholders rather than investing in the company and its workers is not sustainable. Larry Fink, CEO of Blackrock, the multi-billion dollar investment conglomerate, warned corporate leaders against seeking to “deliver immediate returns to shareholders, such as buybacks…while underinvesting in innovation, skilled workforces, or essential capital expenditures necessary to sustain long-term growth.”

Former U.S. Vice President Joseph Biden recently claimed that the high level of buybacks “has led to a significant decline in business investment” with “most of the harm…borne by workers.”

Jesse M. Fried, professor at Harvard Law School and Charles C.Y. Wang, professor at Harvard Business School wrote the following in the Harvard Business Review.

Corporate leaders can profit from a payout even if there is no economic benefit to shareholders from distributing the cash, especially when the payout takes the form of a buyback. For example, a repurchase can enable executives to hit EPS bonus targets or engage in indirect insider trading. Such payout manipulation comes largely at the expense of public shareholders, who pay (directly or indirectly) for every extra dollar an executive takes home. It would not affect employees (except to the extent that they are also shareholders). Shareholders would lose even more if the cash distributed to boost an executive’s pay would have earned them a higher return inside the firm than outside it.

The Buyback Letter is a monthly online newsletter that shamelessly spells out to investors how they can take advantage of buybacks.

By investing in these companies, you are putting the powerful forces of supply and demand to work in your favor. When a company buys back its own stock, it reduces the number of shares outstanding, which gives each remaining shareholder a larger percentage of ownership in the company. This often results in lower price/sales, price/earnings and price/cash flow ratios for a company’s stock, which then can lead to higher share prices and better-than-average returns.

The price-to-sales ratio (Price/Sales or P/S) is calculated by taking a company’s market capitalization (the number of outstanding shares multiplied by the share price) and dividing it by the company’s total sales or revenue over the past 12 months. The lower the P/S ratio, the more attractive the investment.

Critics of buybacks point to the high ratio of shareholder payouts to net income. William Lazonick, professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts, noted that stock repurchases and dividends totaled 91 percent of net income in S&P 500 firms from 2003 to 2012.

—–

Now, to show you how you can innovate, I present HowDo. Let’s build entities that will last, let’s build businesses that will strengthen all sectors of society, and let’s inspire others to do the same.