Startup Accelerator

You will learn how to build a startup accelerator inside your corporation. When used correctly, startup accelerators allow companies to build valuable partnerships, identify corporate venture capital and M&A targets, and gain positive press—all while creating a culture of evolution.

In this training, you will

- Learn how to build a startup accelerator.

- Choose the design, duration, location, sector and learning process for your accelerator.

- Market your accelerator.

- Choose the startups for your accelerator.

- Select mentors for the startups in your accelerator.

- Manage the startup accelerator.

- Ensure the success of your accelerator after the cohort has left.

Skills that will be explored

Introduction to Corporate Accelerators

In an age of innovation, even large corporations must be entrepreneurial. Established organizations and startups can clearly help each other, but collaboration between them has not always been fruitful. According to the joint research report The State of Corporate/Startup Collaboration by Imaginitak and MassChallenge: “While 86 percent of large organizations view innovation as crucial to their future, most of their current attempts to work with startups to further that objective are early stage, underfunded and scattershot, such that 25 percent of corporations aren’t even sure how much they’re spending.”

It’s not enough to buy your team some company hoodies or put a ping-pong table in the break room. Companies must have a concise and thoughtful plan to engage startups. Imaginitak/MassChallenge report that 82 percent of corporations view interactions with startups as at least somewhat important, and 23 percent called them “mission critical.” “Our research found that although nearly three-fourths of large companies (71 percent) reported successful collaboration with entrepreneurs, unfortunately little more than half of entrepreneurs (57 percent) agreed. This gap must be closed.” – Accenture, 2015.

Partnerships with startups are no longer nice things to have. They’re crucial.

Corporate accelerators represent a new frontier in the startup ecosystem. There’s no shortage of high-quality information about accelerators, but at this early stage, that information is scattered all over the internet. Finding impactful information in one place, organized and usable, has been difficult. Until now.

What follows is a curated resource for creating a corporate accelerator. Founders, mentors and alumni share wisdom in interviews and blog posts. Governments, organizations, and individual researchers collect and analyze data to determine accelerators’ impact and outcomes. And I, West Stringfellow, HowDo’s Founder and CEO, proposed, built, and managed a Techstars Accelerator at Target. I then took the learnings from Techstars and created several bespoke accelerators for Target. It is with this foundation in traditional accelerators and corporate innovation strategies, that this guide breaks down the core competencies necessary to tap into the entrepreneurial ecosystem via the accelerator.

Defining Startup Accelerators

The current trend in corporate innovation is startup engagement, but this terminology is confusing. Accelerators are described as incubators, and the institution that inspired this phenomenon (Y Combinator) calls itself a “new model for funding early stage startups.”

Researchers have tried to mitigate the confusion by clearly defining different startup support models. Two of the researchers on the forefront of accelerator research, Susan G. Cohen and Yael V. Hochberg, defined a seed accelerator as follows:

“A fixed-term, cohort-based program, including mentorship and educational components, that culminates in a public pitch event or demo-day.”

—Cohen, Susan and Hochberg, Yael V., Accelerating Startups: The Seed Accelerator Phenomenon (March 30, 2014). Available at SSRN https://ssrn.com/abstract=2418000 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2418000

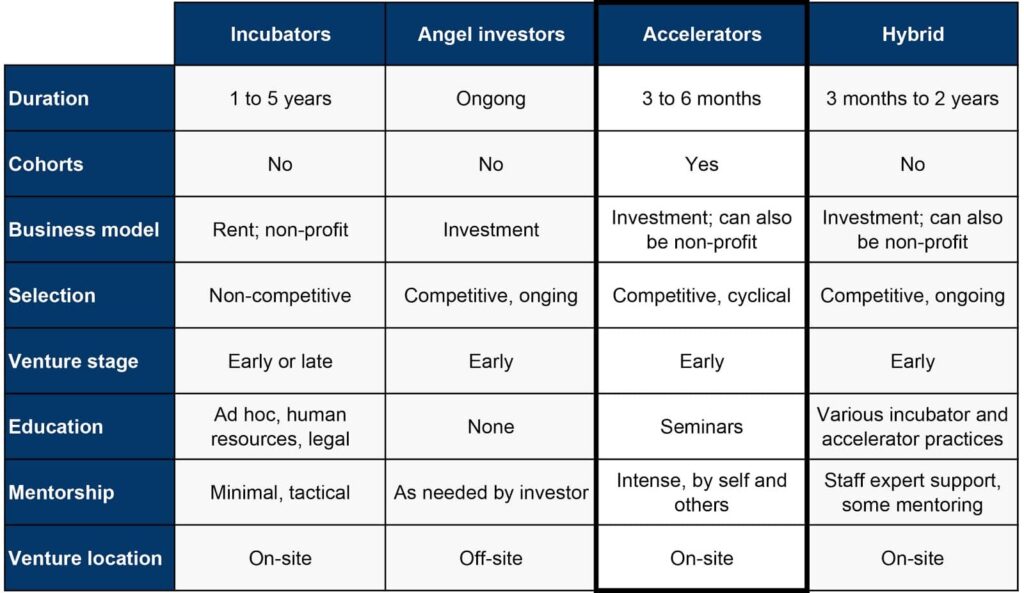

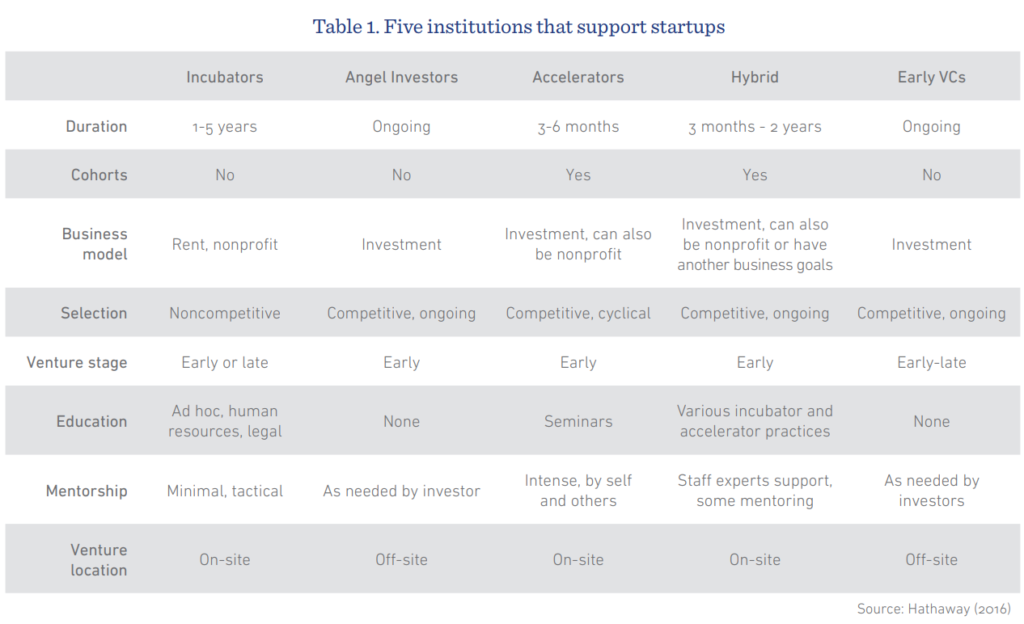

Accelerators are sufficiently different from their incubator counterparts and other innovation tools. The chart below provides a visual representation of these distinctions.

Figure 1: Comparison of startup support institutions

Image Source: Brookings

Accelerators, then, are typically of limited duration—a period of immersive education. They help startups define and build products by identifying promising customer segments and by securing resources such as seed capital, employees, and work space.

A huge consideration for innovators and entrepreneurs is that accelerators open doors and networking opportunities. Program participants gain access to peers and mentors who include successful entrepreneurs, program graduates, venture capitalists, angel investors, and corporate executives.

A Short History of Modern Startup Accelerators

“Y Combinator is just accelerating a process that would have happened anyway.”

— Paul Graham, 2005

The accelerator concept didn’t emerge in a vacuum; rather, it is a concept that grew out of a need for an improved process behind VC investments.

In March of 2005, Paul Graham and Jessica Livingston came to the conclusion that current trends in VC investment were lacking. They suggested that VCs should make frequent, smaller investments, as opposed to fewer, larger investments. With the help of Robert Morris and Trevor Blackwell, the team, under the name “Y Combinator,” started the Summer Founder’s Program to test out this theory.

The Summer Founder’s Program pulled from a mix of traditional seed funding and business-incubator traits. The program gave bright college students a chance to create something amazing with their friends while, at the same time, allowed Y Combinator to uncover an important new strategy for venture capitalists: making multiple, small, and synchronous investments across a cohort of startups. That first Summer Founder’s Program provided a spark that disrupted the investment world; It essentially created a system that gave venture capital the ability to scale.

Y Combinator created a system that:

- Targeted a large number of startups, thereby distributing risk and increasing chances of breakout success;

- Accelerated exits either through acquisition or cohort dropout; and

- Improved over time as graduated cohorts came on as both mentors and investors in the system.

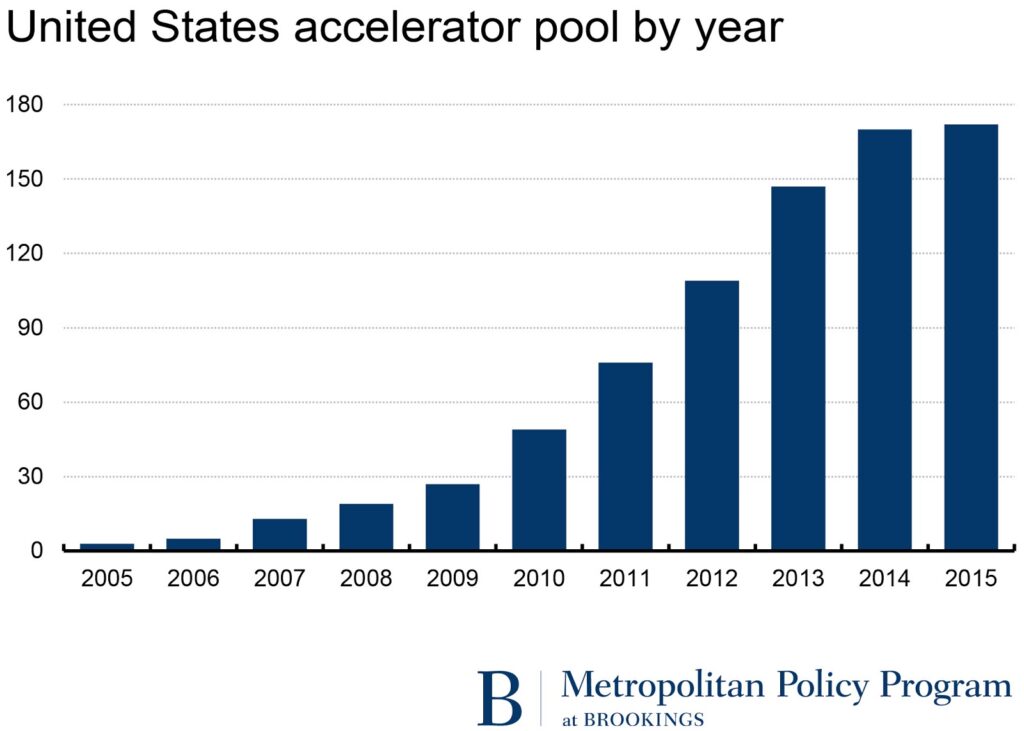

This new system did not go unnoticed. The early success of Y Combinator inspired other investors and, within several years, similar programs started to emerge. Early efforts included the following:

- 2005: Y Combinator first cohort

- 2007: Techstars first cohort

- 2007: SeedCamp first cohort

- 2008: Dreamit ventures first cohort

- 2008: AlphaLab first cohort

- 2009: Founder Institute first Cohort

Image Source: Brookings

Defining Corporate Accelerators

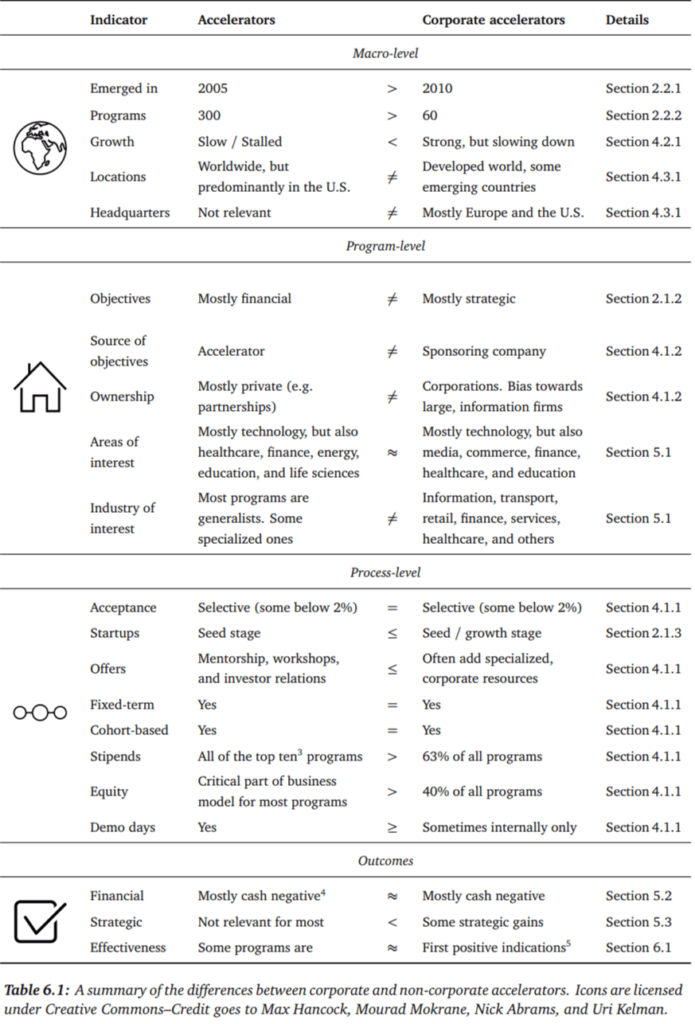

The corporate accelerator closely mirrors independent seed accelerators but there are important distinctions: the objectives of corporate accelerator programs are driven by corporate objectives and these programs are largely owned and run by organizations not traditionally in the business of working with startups.

There are also other differences between corporate and seed accelerator programs, processes, and outcomes.

Key differences between independent accelerators and corporate accelerators

Image Source: Florian Heinemann

As illustrated above, different tools are used to achieve specific goals. Accelerators are exploratory. The best results are seen after both networks and visibility have a chance to grow. If you need faster results, consider other innovation tools like M&A. If you need help choosing and implementing the right innovation tool for your company, contact us.

The Rise of Corporate Accelerators

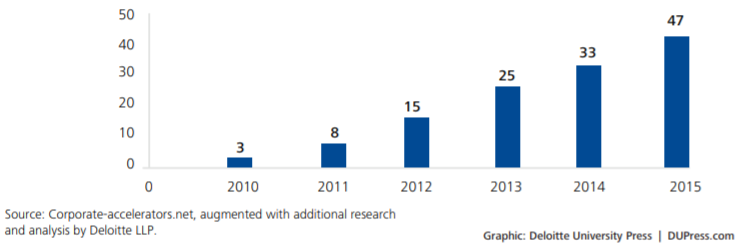

Five years after the emergence of Y Combinator, corporations began to experiment with the accelerator model. Among the first corporate accelerators were Citrix (USA), ImmobilienScout (Germany), Microsoft (USA), and Telefónica (Spain).

This phenomenon emerged at a time when firms were holding on to record amounts of cash and were looking for low-risk growth opportunities in the wake of the Great Recession. Corporate accelerators allow companies to investigate startups that are aligned with their strategy while leveraging their current workforce and providing minimal capital. These factors, combined with the increasing interest in innovation among CEOs, created a fertile ground in which corporate accelerators thrived.

By 2016/2017, there were 188 total accelerators and 71 active corporate accelerators.

Corporate Accelerator Adoption, 2010-2015

Image Source: Deloitte

Advantages to Corporate Accelerators

Corporate accelerators exist at the sweet spot among a number of variables: risk level, capital investment, access to the external ecosystem, and engagement level. This positioning offers a wide variety of incentives for corporations.

- Access to talent: Startups can provide a source of high-quality talent for the host corporation. Through an accelerator program, a corporation can observe startup teams and, upon completion of the cycle, potentially bring team members on board, either through an acquisition or by targeting specific team members.

- Proximity to emerging technology and trends: Startups occur naturally at the cutting edge of technology. By immersing themselves in the startup ecosystem, corporations gain insights into new technologies and business models (among other things) that can be applied to other business segments.

- Open-source R&D: Corporate accelerators provide a venue for multiple industry-specific experiments. Corporations can observe how new ideas succeed or fail without having to deal with the costs or logistical hurdles associated with traditional R&D.

- Financial returns: If the corporation chooses an equity stake in a participating startup, the corporation may experience financial gains if the startup grows rapidly or is acquired. (Deloitte)

- Innovative culture: When a corporation is engaged with the startup ecosystem, the entrepreneurial mindset rubs off on the company’s culture. Internal employees have the opportunity to become mentors, attend seminars, and interact with the startups. These new ideas help spur innovation throughout the company.

- New partnerships: The creation of a corporate accelerator sends a signal that a corporation is committed to engaging in the external innovation system. Other corporations within the industry often seek guidance or partnerships with corporate acceleration leaders. (Forbes – Microsoft)

1: Choose the Design

Not all corporate accelerators are the same. According to Yael Hochberg in “Innovation Policy and The Economy,” there are five main variations of the corporate accelerator.

- Corporate involvement in existing accelerators: Corporations and their executives join existing accelerators as mentors or investors.

- Outsourcing accelerator creation: A corporation contracts with an independent group to run the accelerator on its behalf.

- Joint accelerator partnerships: Corporations partner with other corporations to create joint accelerators (usually focused around an industry).

- In-house accelerator with an external focus: Corporations create their own internally powered accelerator with outside applicants.

- In-House accelerator with an internal focus: Corporations can create a completely internal program that accelerates internal teams.

Each of these models can succeed in an appropriate environment, but the selection of one model over another is dependent on the company’s needs and available resources. For instance, an in-house accelerator will be more expensive than a joint accelerator partnership. We investigate this issue deeper in the final section of this guide on accelerator management.

Model considerations by dimension

Image Source: Digital M Partners

While corporate accelerators may seem like they are all the rage these days, they’re not always appropriate for every company—and they’re not the only option. Accelerators are just one tool the innovator can use to engage in the startup ecosystem. Explore other possible innovation tools here (add link).

Corporate accelerators must be tailored to the needs of the organization and its goals. Broadly speaking, there are four components to the design: Duration, Location, Sector, Learning.

2: Choose the Duration

“We discovered [the three-month program length] by accident. When we first started YC [Y Cobinator], we began with a summer program. We were trying to learn how to be investors, so we invited college students to come to Cambridge and start startups instead of getting summer jobs.”

— The F|R Interview: Y Combinator’s Paul Graham, Carleen Hawn, May 2008

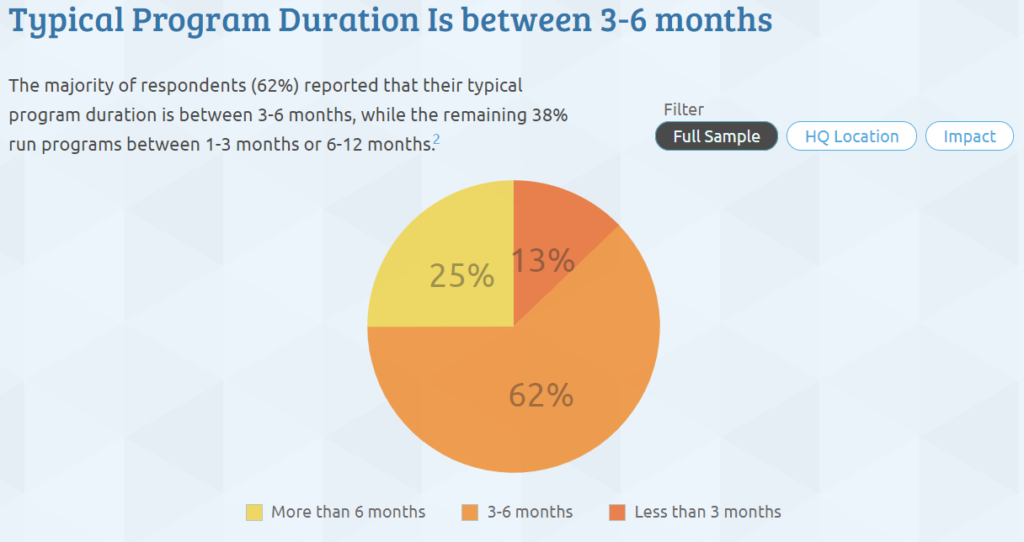

The three-month program may of Y Combinator was discovered accidentally, and it created a new dimension of the startup that leverages the time constraint. However, although the most public accelerators (Y Combinator and Techstars) have chosen the three-month approach, you should design your programs according to the type of product you are focusing on and the amount of capital you have available.

Consider the Product Type

The first thing for an accelerator to consider is what type of product is being developed. While tight deadlines can inspire action, startup founders need enough time to develop a demo product that they can pitch by the end of the program.

“Copying Y Combinator without a reason is a poor choice,” wrote Jed D. Christiansen in his MBA dissertation Copying Y Combinator. “New program founders should specifically think about the reasons behind the length of their accelerator program.”

The three-month window may be ideal for web or mobile applications with typically low capital requirements and short prototyping durations, but if a startup has to build a physical product, it’s going to need more time.

Consider Cost and Efficiency

“Part of the power of the accelerator is that it’s a constrained period of time.”

— Brad Feld and Ian Hathaway Discuss Accelerators, Ian Hathaway, September 2015

As Christiansen noted, most of the funded startups at Y Combinator are unable to launch in the three-month window before Demo Day, but the accelerator has stuck to that length. “We kept the three-month cycle because it is a good length of time to build a version 1,” Y Combinator co-founder Paul Graham said,. “Some startups may not be able to launch in such a short time, but they should all be able to build something impressive.”

A short timeframe puts pressure on startups, but it has other benefits as well. “The limited duration is essential to controlling costs and increasing the number of startups in the accelerator’s portfolio,” wrote the authors of the Small Business Administration report “Innovation Accelerators: Defining Characteristics Among Startup Assistance Organizations.” “This in turn increases the expected profit of the accelerator by increasing the probability of one or more high value exits into the marketplace.”

3. Choose the Location

“There is a start-up revolution occurring. Every major metro area in the world will eventually be able to support an accelerator.”

— Future Techstars, Step Forward, Max Chafkin, April 2012

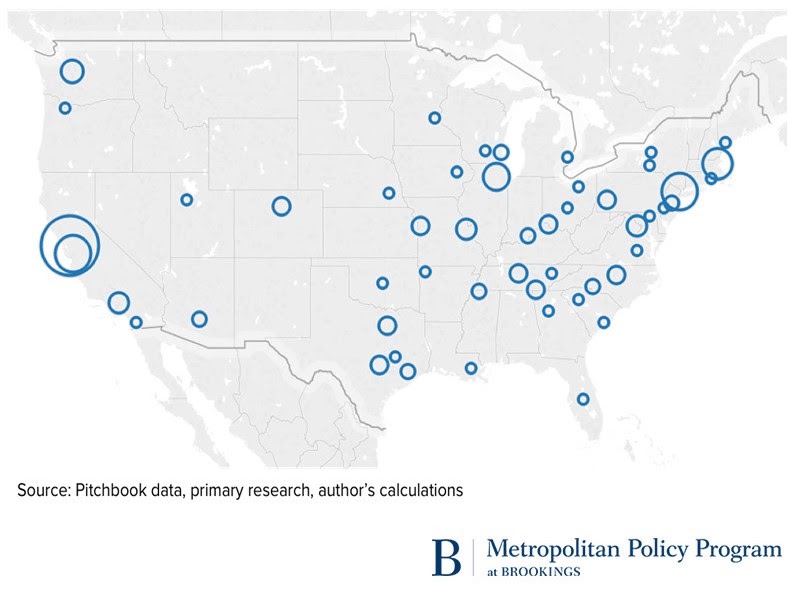

There are generally two schools of thought when it comes to startup accelerator location. One school believes that startup accelerators can thrive anywhere. Brad Feld, who co-founded Techstars in Boulder, Colorado, wrote in Inc. Magazine that “A good accelerator can be run in any city in the world for $500,000.”

The other school believes that Silicon Valley is the best place in the world to house an accelerator. At the Etohum San Francisco 2015 event, Y Combinator’s Michael Seibel said, “We think it’s just ridiculously important to have YC in the [Silicon] Valley. I don’t think we’re ever going to launch an international chapter of YC. The advantages of the Valley are that we can introduce people to money and good valuations, we can introduce them to tons of other companies that can be mentors and customers, and we can introduce them to the pace of the Valley — the speed that you have to operate. We can’t do that anywhere else.”

Both schools agree that accelerators are more successful when they’re part of a thriving ecosystem. But while Graham says startups should seek out an industry or startup ecosystem, Feld argues that entrepreneurs can create their own.

“I’m not claiming, of course, that every startup has to go to Silicon Valley to succeed,” Graham wrote on his website. “Just that all other things being equal, the more of a startup hub a place is, the better startups will do there.”

Accelerator Programs by Metropolitan Statistical Areas (2015)

Image Source: Brookings

Feld disagrees: “I think it’s unbelievably myopic to say the only place you can build your company is Silicon Valley or City X,” he told Marketplace. “It goes against the law of systems dynamics — if everyone goes to a certain place to do a certain thing, you’re not going to have increasing returns forever. You should decide where to live your life, and then build your life around that.”

It’s worth noting that Feld considers the startup process to have a longer timeframe than most entrepreneurs think about: “It takes 20 years to create a company,” he told the Wharton School in 2013. “The startup community needs that kind of 20-year time horizon.”

All this said, corporations are generally constrained to the areas where they already operate. Therefore, before moving forward with any accelerator plans, assess your city’s innovation and startup potential.

External Resources

The following resources provide general insights into existing and emerging accelerator hot spots:

- Top 10 Cities for Corporate Innovation: Innovation Leader magazine’s ranking of cities based on ecosystem for supporting corporate innovation.

- TechCities 1.0 Report: Cushman & Wakefield look at the big player tech cities in the United States for 2017 and those to watch in the future.

- Global Cities 2017: Leaders in a World of Disruptive Innovation: This analysis by A.T. reports the world’s most influential cities.

- Map: Emerging tech hubs and specialization: Marketplace’s coverage of cities that have the potential to become the next Silicon Valley.

- The 2017 Kauffman Index of Startup Activity: The Kauffman Institute investigates startup activity by analyzing the rate of new entrepreneurs, the opportunity share of new entrepreneurs, and the startup density of a region. Reports are organized by city, state, and nation.

- Beyond Metropolitan Startup Rates: Regional Factors Associated with Startup Growth: This paper from the Kauffman Institute reports on entrepreneurship activity in 356 U.S. metropolitan areas with a focus on the startup rate for all industries, the startup rate for high-tech sectors, and the rate for high-growth firms.

- Measuring an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem: The Kauffman Institute offers 12 indicators for measuring the outcomes and vibrancy of a local entrepreneurial ecosystem.

- Can You Buy a Silicon Valley? Maybe: Paul Graham offers a less technical overview of how a city can transform into a tech hub.

4. Choose the Sector

A major benefit of focusing on teams in one sector is that the ventures benefit from sharing expertise because they are working on related problems or technologies. Similar teams in one cohort also facilitate collaborating with investors and partners who are active in the particular sector.”

— Corporate accelerators: Building bridges between corporations and startups, Thomas Kohler, 2016

The accelerator space is saturated with incumbents that have controlled the generic market for years. Most corporate accelerators have addressed their lagged entry by focusing on their specific vertical.

“By concentrating on one specific sector, the accelerator management team can develop the necessary sector-specific knowledge and expertise to identify and exploit the economic potential of entrepreneurial teams,” wrote the authors of the report “A Look Inside Accelerators” by the U.K. foundation Nesta.

Focusing on a corporation’s own industry allows an accelerator to take advantage of various synergies that can help a startup succeed. As the DEEP Centre report Global Best Practices in Business Acceleration noted, these can include global value chains, hands-on mentorship, and exposure to the corporate partner’s executives, employees and customers.

To date, two industries have dominated the growth in corporate accelerators. Half of the corporations that have launched accelerators are in technology, media, and telecom, while almost a quarter are in financial services. Both industries are being transformed by digital technologies.

“Corporations within these industries should pay particular attention to this emerging innovation model—as their competitors already are,” wrote John Ream and David Schatsky in Deloitte Insights. “Corporations in industries with lower accelerator adoption may want to explore the model as a distinctive innovation tactic that may help drive unique capabilities among their peers.”

In any industry, focusing on the sector correlates with startup success. A 2015 global survey on best practices in incubation and acceleration by Unitus Seed Fund and Capria Accelerator Fund found that 70 percent of startups in the top quartile of success “have a deep sector focus; the second and third quartile both have 50 percent who have a sector focus and only 10 percent of those in the lowest quartile of success have a sector focus.”

Corporations are in a prime position to provide startups with support in their respective industries. Innovation leadership must keep an ear to the ground and determine whether the industry is ripe for corporate support. The following are a small sample of resources for insights into disruptive trends.

Which leads to the next question: Is your sector ripe for disruption?

Below are two resources for insights into industry and sector trends.

- Industry Market Map Landscape: CB Insights’ market maps and unbundling/disrupting graphics covering a variety of industries.

- Mary Meeker’s Internet Trends: A state-of-the-industry report by the Kleiner Perkins venture partner.

5: Design the Learning Process

“You’re just trying to accelerate time so in three months you’re trying to get two years’ worth of learning about your business to happen.”

— Brad Feld and Ian Hathaway Discuss Accelerators, Ian Hathaway, September 2015

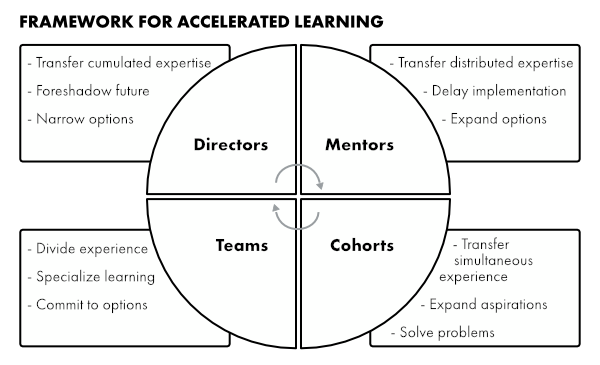

Accelerators transform not only startups, but the founders themselves. To keep their heads above water, founders have to learn to move quickly. The learning dynamic within accelerators is complex. Anyone with the intention of building an accelerator would be wise to read Susan L. Cohen’s How to Accelerate Learning: Entrepreneurial Ventures Participating in Accelerator Programs. This study lays out a learning framework based on the structural elements of the accelerator. That includes directors, mentors, cohorts and teams, as well as how time constraints can affect learning.

Image Source: Cohen, Susan Lee. 2013. How to Accelerate Learning: Entrepreneurial Ventures Participating In Accelerator Programs. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. https://doi.org/10.17615/m5ja-aq03

Looking beyond the indirect learning factors, accelerators must plan some sort of education curriculum. While 97 percent of accelerators offer business skills training, training/education offered at accelerators is far from uniform. Effective training methods vary widely based on the topics covered, time spent in class, cohort size, location, etc.

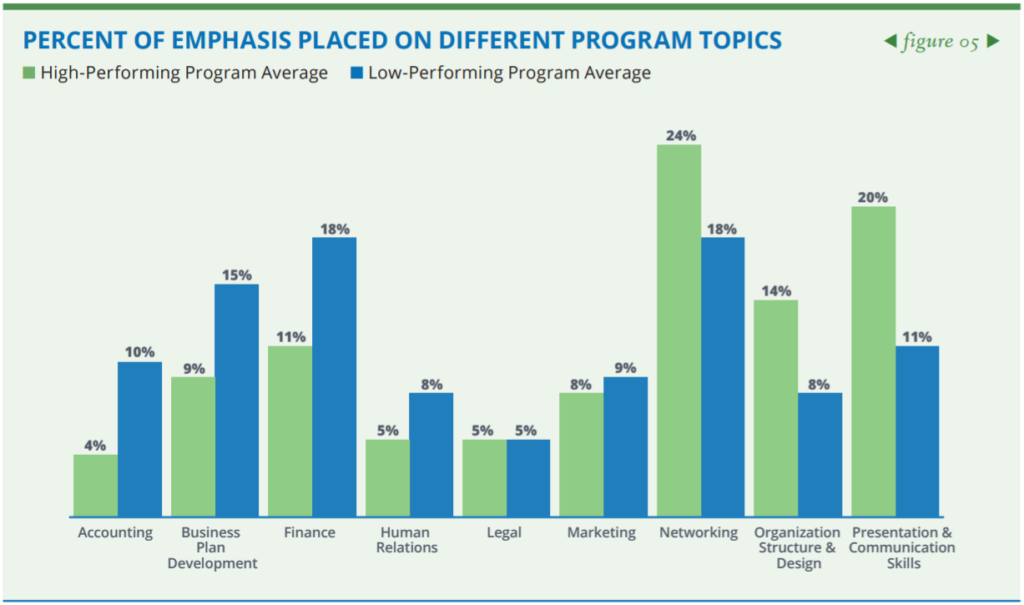

What’s Workingin Startup Acceleration, a study of 15 Village Capital programs by the Global Accelerator Learning Initiative (GALI), found that high-performing programs spent less time working on finance, accounting, and formal business plan development and more time on presentation skills, communication skills, networking, organization structure. and design.

Image Source: GALI, 2016

Accelerators must focus on the practicalities of innovation, not the intricacies of double-entry bookkeeping. Many promising entrepreneurs don’t have access to resources because they don’t have the right networks. They didn’t go to the right schools or don’t speak the same language as emerging market investors. (This is part of the reason for HowDo; to provide a baseline for people to discuss innovation and growth. If you need help building a bespoke education program for your accelerator, Contact HowDo.)

So, while understanding financials is necessary for running a business, it’s not the best use of accelerators’ time. When planning the education curriculum, there should be less concern with the output and more focus on perfecting what goes into creating output that has value.

According to a Whitepaper by Impact Accelerator, startups most request courses on user experience, digital marketing, and SEO optimization.

Consider the Educational Program Structure

“Less is more’ when it comes to program content. Programs where entrepreneurs spend a lot of time in the classroom — listening to guest speakers or to us teaching — have inferior outcomes.”

— What’s Working in Startup Acceleration, GALI

When there’s teaching to do, it’s tempting to sit students down in a classroom and show them what they need to know. But GALI found that “the more remote work we allow, the better.” Indirect learning, which focuses on the student’s inquiry and exploration rather than the teacher’s instruction, allows entrepreneurs to learn while working on their business plan and product.

According to the authors of a research paper titled “Do Accelerators Accelerate? The Role of Indirect Learning in New Venture Development:” “Much of the benefits of accelerator participation likely stems from accelerators providing opportunities for indirect learning that help entrepreneurs correct known and unknown flaws and gaps in their initial business plans and identify unexpected possibilities for improvements (e.g., target customer, go-to-market plan, technology and operations strategy, profit formula).”

Accelerators should design curricula around things entrepreneurs do remotely that serve the dual function of teaching valuable lessons and helping advance the startup. Time on site is better used in building relationships.

Some accelerators are beginning to blend online education with the accelerator experience. This allows founders to spend more time building both networks and product.

Where the corporate accelerator is located and how many entrepreneurs it’s trying to serve will both influence the design of the curriculum.

“Accelerators that operate in regions without a strong history of entrepreneurship will need to create a more comprehensive educational program,” wrote Christiansen in Copying Y Combinator, “while accelerators that focus on more experienced entrepreneurs can likely be successful with a more tailored educational program.”

As in any other educational setting, the smaller the cohort, the more specialized and individual the teaching can be. But even in larger programs, it’s important that all entrepreneurs get some education tailored to their startup.

“In larger education programs, the advice must be biased toward the general in order to be effective,” Christiansen wrote. “But product-specific advice and education can be invaluable to the long-term success of a company, and should be included as a part of every accelerator program.”

External Resources: Accelerator Education Programs

Here are some examples of general entrepreneur education curricula aimed at larger, industry-agnostic cohorts.

Additionally, the smaller the cohort, the more specialized and individual the teaching can be. But all entrepreneurs require some education that is tailored to their startup.

6. Market Your Accelerator

Once a corporation understands what startups are hoping to get from your corporate accelerator, the marketing can begin. Managing expectations from the get-go saves everybody a lot of time. Clear communication about the program’s criteria, what it offers, and to whom, will help the startups understand what’s in it for them. This way, the corporation can be confident that any applicants are at least on board with the bare bones of the program.

Selecting the channels through which to deliver the message depends on where the company has influence. For example, Sam Altman of Y Combinator states that an online class he taught boosted the entrepreneur applicant rate by 40 to 50 percent. For another company, an alumni network might be a more lucrative channel.

According to the report Bridging the “Pioneer Gap” by the Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs and Village Capital, the most common sources accelerators cite for startups are:

1. Referrals from entrepreneurs affiliated with the accelerator.

2. Impact investors (individuals and investment funds).

3. Commercial investors (individuals and investment funds that do not self-identify as impact investors).

4. Entrepreneurial associations (fellowships, scholarships) in the social impact space.

5. Entrepreneurial associations that do not identify with social entrepreneurship or impact investing.

6. Universities.

7. Sector-specific industry associations.

8. Sector-specific conferences (e.g., agriculture, education).

9. Social entrepreneurship or impact-investing conferences.

10. Inbound requests from program marketing efforts and social media.Outbound direct, “cold call” recruitment (e.g., finding and contacting entrepreneurs on the web, Facebook, LinkedIn).

The report notes, however, that not all sources are equally helpful, and a corporation should decide where its outreach efforts will get the most bang for the buck in terms of attracting quality applicants, not quantity.

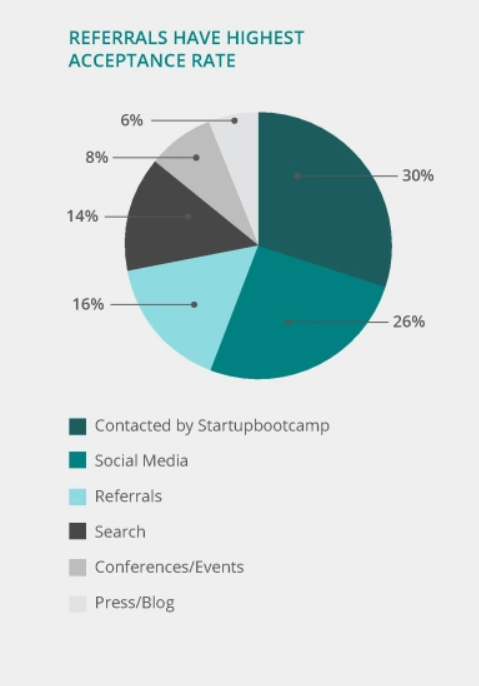

Startupbootcamp, which runs accelerator programs around the world, published a Startup Ecosystem Analysis for the year 2016. The accelerator ran 266 mentorship events in 53 countries in 2016, nearly double the number from 2015. It also finds teams at major conferences and industry events. Startupbootcamp representatives attended more than 40 such events in 2016, including Pioneers Festival in Vienna, RISE in Hong Kong, and Wolves Summit in Warsaw.

The program also relies heavily on referrals. More than a quarter of Startupbootcamp’s startup teams came through referrals from mentors, alumni, investors, and staff members.

Image Source: Impact Accelerator

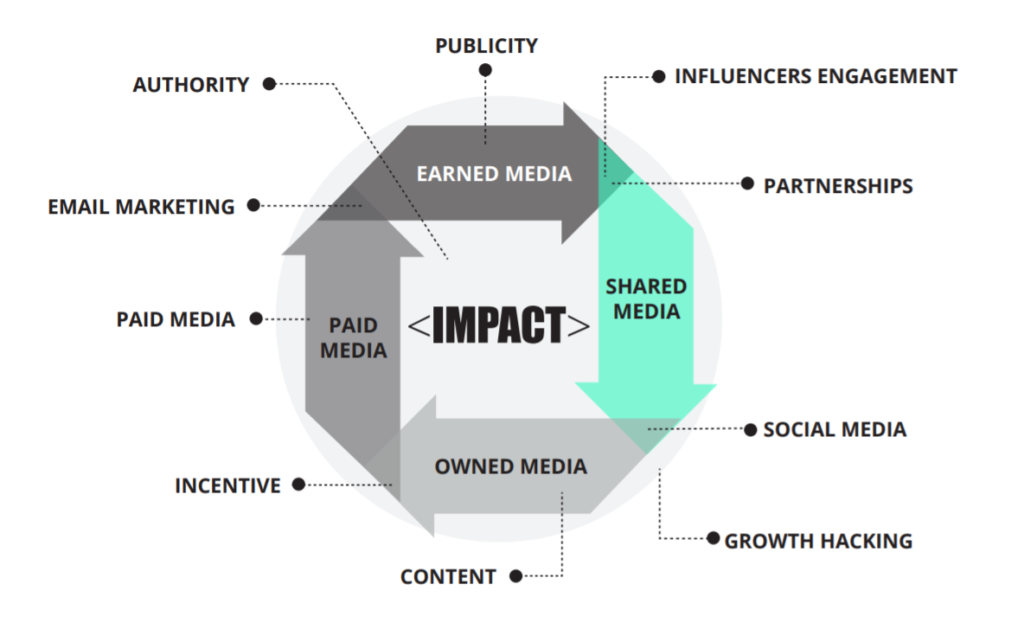

In its whitepaper, Impact Accelerator provided examples of its outreach approach, which includes using a network of earned, owned, paid, and shared media to reach as many people as possible. Messaging channels include live presentations, webinars, hackathons, traditional media, and social media.

Image Source: Impact Accelerator

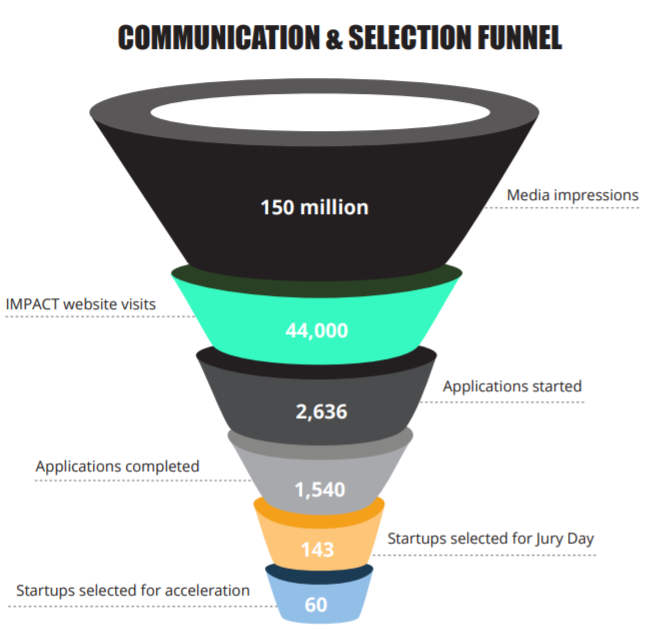

According to Altman, one of Y Combinator’s problems is that the top of their funnel is so large, and the sheer number of applicants so vast that the program risks discarding some of the good applicants with the bad.

The figure, below, shows the selection funnel for Impact Accelerator. In this case, of 160 million applicants, only 60 were selected.

Image Source: Impact Accelerator

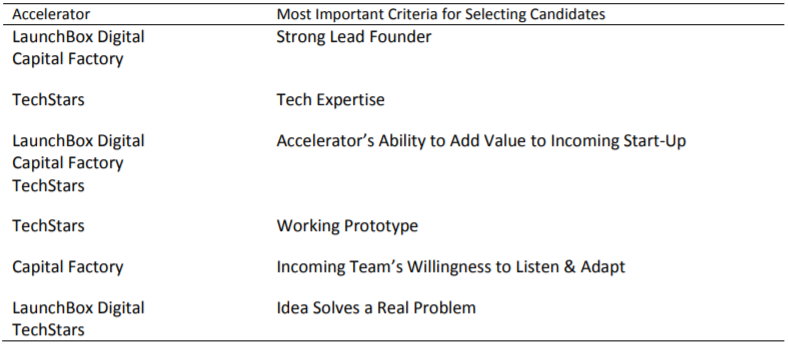

The precursor to screening applicants is to develop selection criteria that are unique to the company-accelerator context. A case study by the Small Business Institute Journal examined leading accelerator companies in the United States. It found that each had a different set of criteria for selecting participants.

Selected startups or teams must have the elements necessary to succeed, including sufficient experience, a good product, a receptive market, and a plan. Even with these clear criteria, selecting startups to participate in an accelerator isn’t easy; accelerators that have been around for more than a decade admit that it’s messy and imperfect.

7: Select the Startups for Your Accelerator

Corporate accelerators should be selective about the startups they bring into their programs. Although receiving a flood of applications might seem like a way to cherry-pick the most promising candidates, according to the Unitus Seed Fund/Capria Accelerator Fund survey, the most successful accelerators put out significant effort to ensure a good fit.

Entrepreneurs participate in accelerators for a variety of reasons, but funding and connections are at the top of the list. In Jed D. Christiansen’s dissertation, Copying Y Combinator, the most popular reasons were connections to future capital, brand connections, business support, product support, and financial support and initial funding, in that order.

John Ream and David Schatsky more recently explored what attracts startups to corporate accelerators for Deloitte Insights. They found four driving factors:

Equity-free funding: It’s still common for corporations to acquire equity from startups they bring into their accelerators, but Deloitte’s analysis found that Samsung, Microsoft, and Google have all adopted equity-free funding, which is perhaps an indicator of the increasing demand for talent.

Industry-focused mentors: Mentors are crucial to a successful accelerator program, and startup founders often cite mentors as the single most important element. When corporations focus their accelerators on their own industry, entrepreneurs can tap into experts in the field, from executives and business unit leaders to product managers and technical experts.

Corporate resources: Access to proprietary resources can be a critical differentiator for an accelerator program. Qualcomm, Samsung, and Barclays all provide startups with data, internal tools, and intellectual property. These ready-to-use established resources are integral to rapid startup development.

Future customers: The corporate sponsor, and its market, are obvious early customers for a startup. Vending Analytics is a startup whose product uses data analytics to optimize vending machine stocking. The company was spawned by Coca-Cola’s Founders startup incubator, so it wasn’t surprising when Coke signed on to use the product. As a result, the soft-drink giant realized a 20 percent increase in revenue per machine.

— Deloitte

Timeline for Selection

In terms of the timeline for the selection process, most accelerators spend between one and three months recruiting each new cohort, according to both Bridging the “Pioneer Gap.”and “Startup Accelerator Programmes: A Practice Guide.” One-third spend between three months and a year.

Selection processes have evolved over the years as accelerators have gained momentum within the startup community. As the numbers of applicants continue to increase, video applications and the use of alumni help weed out poor prospects.

In contrast to the relatively short duration of the actual accelerator, the time spent in talent selection is substantial. According to Nesta, it’s common practice for accelerators to use selection committees composed of strategic partners, investors, alumni, and experts or mentors. Applicant interviews with these committees can range from a short, informal chat to an hour-long inquisition.

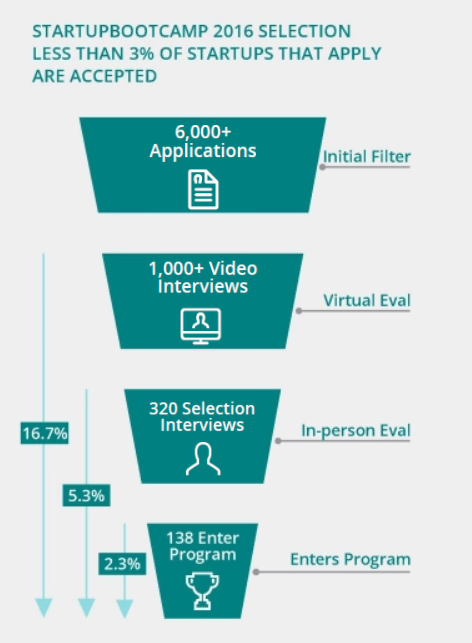

A graphic from Startupbootcamp shows their funnel-shaped selection process at the end of which only three percent of applicants are accepted.

Image Source: StartupBootCamp

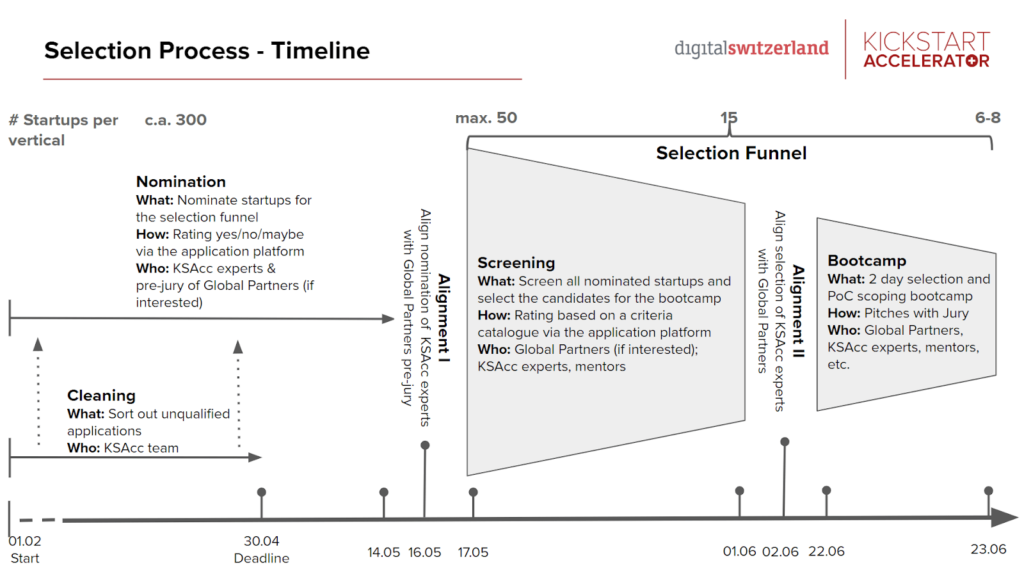

This detailed example of Kickstart Accelerator’s selection process and timing includes graded criteria.

Image Source: Kickstart Accelerator’s selection process

Nesta’s “Startup Accelerator Programmes: A Practice Guide” includes examples of accelerator selection processes from Techstars London, Fintech Innovation Lab, and Bethnal Green Ventures. While all three use online applications, their methods diverge after that. Techstars and Bethnal Green end the process with a face-to-face committee interview, whereas Fintech puts shortlisted candidates through a half-day boot camp during which they trial-run their pitch. In between, all three have expert and/or executive review teams that create a shortlist.

Selection Criteria

Here arethree questions to consider when designing a startup selection process.

- What key criteria would you look for in your startups?

- How will you structure your selection process to ensure you find the right startups?

- Which other stakeholders could you engage in the selection process?

The Deloitte report, “Design Principles for Building a Successful Corporate Accelerator,” lists questions to ask in the selection process tailored to two different models of acceleration: 1) financial returns, in which the accelerator invests in startups and achieves economic benefit through exits, and 2) innovation integration, in which the accelerator directly integrates innovative technologies or disruptive business models into the corporation’s organization.

Questions for financial returns

1. Will the startup integrate or exit within the next five to seven years?

2. Does it have the potential to return 10 times the funds invested?

3. Does the team have a prototype and traction in the market?

4. Is the founding team visionary, ambitious, and able to scale this business?

5. Is the founding team receptive to criticism and ready to pivot from the original idea if the market demands it?

6. Do we have a network of experts that can help this startup in its specific vertical?

Questions for innovation integration

1. Is this a venture representing the edge of our business?

2. Is the marketing moving in such a way that this innovation could become the core of our business?

3. Do we have the specific resources the startup needs to develop the technology?

4. Do we have a network of experts in this vertical?

5. Is the founding team visionary, ambitious, and able to scale this business beyond borders?

6. Is the founding team receptive to criticism and ready to pivot from the original idea if the market demands it?

— Deloitte

Additional resources for accelerator applicants

- A post by Paul Graham that gives insight into how Y Combinator partners choose cohort members.

- A 2012 collection of questions commonly used in Y Combinator interviews.

Assessing the Founders

Paul Graham and Sam Altman have devised a way of gauging applicants’ potential for success. The method asks applicants to describe a time when they’d hacked something to their advantage or “beaten the system” in some way. This question can reveal initiative, creativity, tenacity, and the ability to think strategically to solve a problem.

Intelligence is not the number one criterion that Y Combinator looks for in applicants. According to Graham, “That’s the myth in the Valley … as long as you’re over a certain threshold of intelligence, what matters most is determination.” Altman lists the following characteristics that he looks for when selecting startups: clarity of vision, clarity of explanation, determination, passion, and evidence that applicants have done something great in the past. Moreover, Altman spends only 10 minutes identifying these characteristics in an applicant.

How do you assess a whole team using these criteria? Graham looks closely at not just how well startup teams work together but also how they get along. The relationship between the founders has to be strong. According to Graham, “Startups do to the relationship between the founders what a dog does to a sock: if it can be pulled apart, it will be.”

8: Select Mentors for Your Startup

Selecting the right applicants is only half the story when it comes to building a corporate accelerator. Top accelerators thrive at the intersection of promising startups and thoughtful mentors. These two groups act as the fuel to create invaluable networks and interactions that lead to a successful and enduring accelerator.

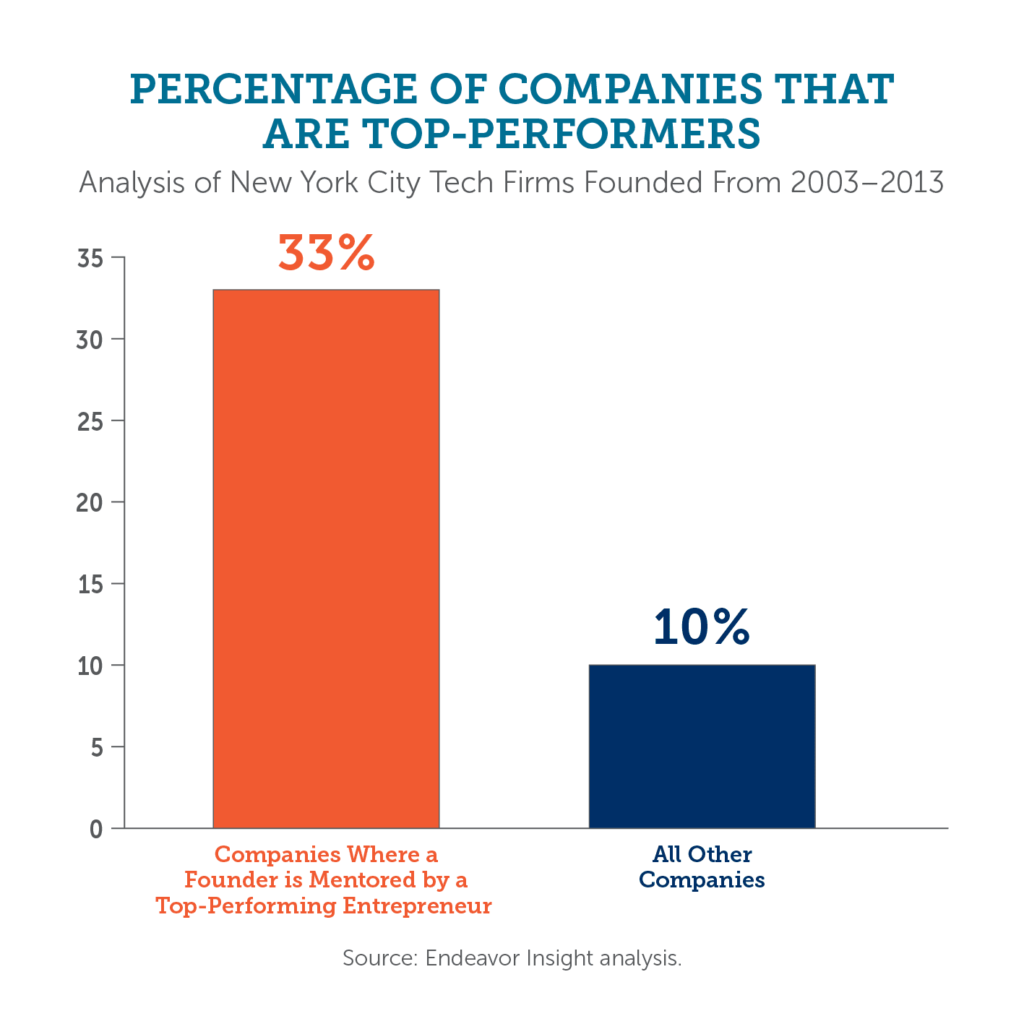

Mentorship is ubiquitous among corporate accelerators, and it works. At their best, mentors can provide startups with advice and access to networks and funding. Having top-performing entrepreneurs as mentors gives a startup an advantage.

Moreover, there’s evidence from GALI that multiple mentors are desirable. More mentors help startups separate ideas shared by successful entrepreneurs from thoughts that may be rooted in personal eccentricities. In fact, parsing the advice and input from mentors within a restricted timeframe and making decisions is one of the most complex and demanding tasks that accelerator teams will face.

Susan L. Cohen noted that involving more mentors can result in conflicting advice but consulting with multiple mentors within a short period can help founders identify commonalities in the conflicting feedback.

Brad Feld noted that information management is a vital part of the learning process. According to Feld, “If you don’t build your own muscle around collecting, synthesizing, dealing with, and deciding what to do with all the data that is coming at you, then you are going to have massive problems as your company scales up.”

Cohen suggests that accelerators schedule meetings for founders, which gives the founders a wider pool of mentors. It’s also likely to result in a more diverse set of mentors than the startups are likely to assemble themselves.

Predictably, not all experts see mentor overload as a good thing. Fred Wilson, an investor, believes that too much mentor feedback creates confusion, wastes time and energy, and even results in loss of confidence. Also, the quality of mentors is bound to have an effect.

Rhett Morris is the director of Endeavor Insight, the analytics and research arm of Endeavor Global. His take is that mentors who had already achieved success in the tech industry were able to help younger tech startups outperform their peers by a factor of three. The benefits from lower quality mentors were much lower. Ravi Belani of Alchemist Accelerator went a bit further at the 2015 Wolves Summit in Poland saying that a subpar mentor can actually do harm to a startup by consuming valuable time.

So where do mentors come from, and how do you separate the wheat from the chaff? Here’s how to select the right mentor.

One method of mentor recruitment is more of a matchmaking process between startups and mentors. In a 2011 report, “Nurturing Innovation: Venture Acceleration Networks,” the World Bank suggests that mentors and entrepreneurs select each other. The idea is that the relationship becomes sticky and long-lasting for a period beyond the scope of the accelerator, creating a stronger entrepreneurship network.

The World Bank report also reviewed the methods used by leading accelerators for mentorship recruitment. Here are some of the methods.

MIT’s Venture Mentorship Service: Mentor recruitment is based on referrals. MIT VMS mentors said their main motivations to join were the following:

- Exposure to interesting MIT start-ups

- The opportunity to educate younger generations

- Connecting with talented people as peer mentors

Techstars: The selection process at this accelerator is informal and based on referrals. The managing directors typically know the mentor candidate directly, or they’re referred to them by a trusted source in their social network. Beyond that, the typical recruitment process is described as follows:

- A short discussion with the mentor and due diligence.

- Mentors are selected for their extensive entrepreneurial experience. Academic credentials do not play an important role in the selection of mentors.

- Mentors looking to develop relationships with companies in view of selling their services are not accepted.

- Mentors are attracted by the high quality of the Techstars startups and of some of the other mentors serving in the program.

Once a company has identified suitable mentors, how is their knowledge best applied? According to venture capitalist and mentor Christopher Quek, there are three areas where mentors are most valuable.

- As domain specialists, such as mentors with experience in specific areas such as finance, education, energy, or health (for digital health technology).

- As skill specialists, for example, mentors who can teach and coach in specific skills such as UI/UX, sales, legal, business, or design.

- As connectors or networkers, for example, mentors who are willing to expand and share their network.

An interesting insight from the GALI study is that accelerator program alumni may not be the best mentors. Moreover, including potential customers as mentors is a good idea, which makes sense given that the consumer is the ultimate judge of any concept or innovation.

External Resources: Corporate Accelerator Mentorship

Recruiting qualified people is only a part of creating a solid mentorship program. Even the highest quality candidates need to be trained in mentorship best practices. The following resources provide insight into successful mentorship models, with a focus on mentoring startups:

- The Mentor Manifesto: The original “Mentor Manifesto,” created by David Cohen with the help of Jon Bradford and Brad Feld, outlines a set of principles supported by years of accelerator work and thousands of mentor interactions.

- Deconstructing the Mentor Manifesto: Brad Feld goes in depth through each component of the manifesto. This series is broken up into 18 promised posts, 16 of which are live.

- MIT’s Venture Mentoring Service: MIT has created a unique model to coach early stage startups. The VMS has trained over 66 organizations from 18 countries on its mentorship model.

- Establishing a Powerful Mentorship Program: Louis Goldish provides an overview of some of the most important characteristics of the VMS model.

- Nurturing Innovation: Venture Acceleration Networks: The World Bank and Russian Venture Company present a review of venture acceleration models.

- How to Build a Successful Mentoring Program: This guide lays out an approach for building mentoring programs within companies.

- How to Maximize the Value of Mentors in Accelerators: Ben Yoskovitz.

Finally, any program needs to be monitored and assessed. The quality of mentorship can be assessed through feedback surveys that the startups complete. This information is part of a feedback loop that allows for constant improvement in the mentorship process.

9. Manage Your Corporate Accelerator

Who “owns” the corporate accelerator? What risks are associated with this tool? What is the timeline for a return on investment?

Independent accelerators typically answer to contributing investors, whereas corporate accelerators answer to the C-Suite, the board of directors, and shareholders. Budget considerations, annual reports, and risk management add a complex layer to accelerator design and management.

Conflicts abound in the governance realm. For example, a typical corporation makes decisions based on an annual schedule, which means, according a CB Insights interview with Dave McClure, that startups live and die within that timeframe. While corporations’ quarterly and annual reports exemplify consistency, startups live in a boom or bust world.

The hope is, of course, that an accelerator is successful, but determining the impact of an accelerator is complex considering the variable ROI expectations of the corporation versus the accelerator.

Leadership and shareholders need to be aware that corporate accelerators rarely lead to instant results, and communication about innovation efforts with longer timelines must be clear. One of the worst possible outcomes for an accelerator is a premature termination.

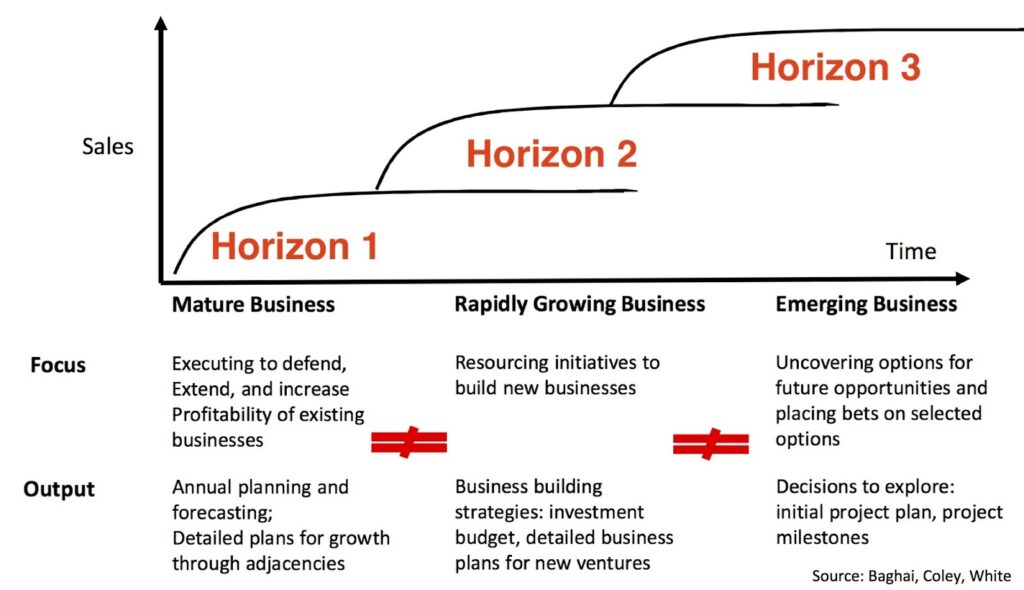

There are several models that address the time required for a measurable impact on a company’s core business. In McKinsey’s Three Horizons of Growth model, corporate accelerators exist around Horizon 3, shown in the illustration, with a timeframe for contribution to growth of approximately five to 12 years.

Image Source: McKinsey

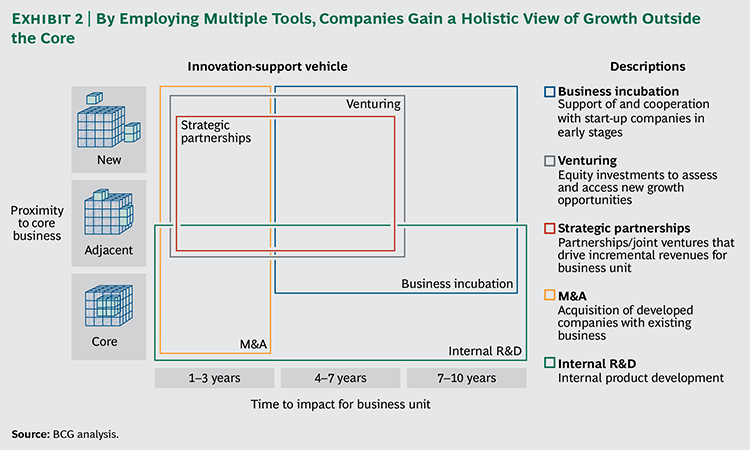

The Boston Consulting Group suggests a four to 10-year timeframe for incubator or accelerator results in their report “Incubators, Accelerators, Venturing, and More.” (Note: BCG includes accelerators in the “Business incubation” segment of the following diagram.)

Image Source: BCG

Managing C-Suite Expectations

“When it comes to building the corporate accelerator, the organization should understand that the process requires time and continuous learning concerning what works best for the organization as well as the startups.”

— Design Principles for Building a Successful Corporate Accelerator, Deloitte, 2015

Communication about innovation efforts with longer timelines has to be clear. Leadership and shareholders need to be aware that corporate accelerators rarely lead to instant results. One of the worst possible outcomes for an accelerator is a premature termination.

“Corporate sponsors of incubators and accelerators bring greater resources to bear, but their commitment to acceleration may change at any time due to factors outside the influence of the program,” wrote the authors of California Tool Works, a report on innovation and acceleration by the California Business Incubation Alliance. “This kind of change often interrupts the operation of accelerators and their associated networks.”

At the CB Insights’ Innovation Summit in January 2017, Los Angeles Times tech reporter Paresh Dave asked 500 Startups founding partner Dave McClure about corporate timelines for accelerators:

Paresh Dave: So, what’s wrong about looking at the five-year horizon and doing that?

Dave McClure: I don’t think most corporates plan for that long. Certainly, most people running corporate accelerator programs, if you look at the trajectory on those, they often aren’t renewed for more than one or two years.

“Building an accelerator is an exercise in ‘business building’ in itself, and is in fact the first step towards an internal ‘business building’ unit for the corporation,” Deloitte wrote in Design Principles for Building a Successful Corporate Accelerator. “This is a concept which we believe will be standard in successful major corporations within the next five years.”

In order for the concept to work, Deloitte wrote, the organization has to understand the mechanisms of early-stage venturing, and that it usually takes five to seven years for early-stage ventures to achieve meaningful financial results. Even a startup that doubles that speed is looking at a two- to four-year timeline.

“This type of accelerator requires a strong long-term financial commitment with lasting C-level and board support, anticipating that the accelerator will most likely be a cost center before achieving returns,” the report noted. “Chances are high that along the way, a significant number of startups will fold or fail to achieve acceptable results.”

Justifying Corporate Accelerator Costs

“A rule of thumb for the financial estimation is to set aside 5-10 percent of the money that the organization would like to see a business create. For example, if the goal is to build a 100 million-euro business, the organization should be looking to set aside 5 million-10 million euros for building and running the accelerator.”

— Design Principles for Building a Successful Corporate Accelerator, Deloitte, 2015

Expenses for a corporate accelerator may include third-party vendors, office space, marketing expenses and internal teams, according to Falguni Desai, managing director of Future Asia Ventures, writing in Forbes. “Budgets to simply run the accelerator can range anywhere from $2 million to $5 million per year,” he wrote. Outsourcing your accelerator to a company like Techstars costs an upwards of $1 million, according to a discussion on Quora.

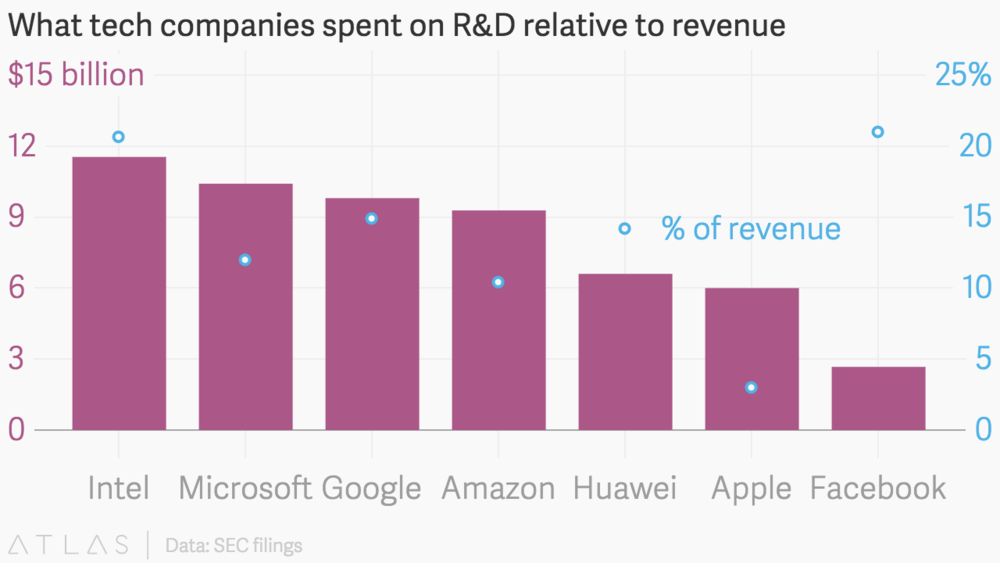

But comparing R&D spending to accelerator expenses adds perspective.

Image Source: The Atlas

The 2016 Global Innovation 1000 study by PwC Strategy shows that the 10 most innovative companies outperformed the top 10 R&D spenders, which refutes traditional theory and past research studies.

No one will be surprised to hear that Apple and Alphabet continue to lead the most innovative list, followed by 3M and Tesla. However, they do so with far less spending on R&D than some big-name industry leaders. Volkswagen, Samson Electronics, and Amazon spent the most on R&D but with little to show for it. Apple spent $8.1 billion on R&D and outperformed Volkswagen in innovation, which spent a colossal $13.2 billion. 3M spent just $1.8 billion on R&D and outperformed Samsung, which spent close to $13 billion.

Depending on strategic motives and company structure, accelerators and corporate venturing could well be a way to save money and complement R&D programs.

According to Yael Hochberg, a visiting professor at MIT Sloan School of Management, startups are about experimentation, and the cost of that experimentation is about one-tenth what it was a decade ago. Hochberg says, “[Businesses] can actually go out and get a sense of whether these things are going to be successful a lot more quickly and at a much lower cost.”

Corporate Accelerator Leadership and Structure

Building a corporate accelerator into an established business requires surgical precision. Proper leadership needs to be in place in order to manage expectations and ensure that both corporation and accelerator are getting what they need.

An accelerator is straddling the line between an emerging concept and a contribution to a mature and established corporation. There is a need, therefore, for an entrepreneurial mindset that also has a deep understanding of the company’s culture, structure, and mission.

Dominik K. Kanbach and Stephan Stubner suggest combining parent-company heads of corporations with over 15 years’ experience, leaders with startup experience, and a network of relevant external stakeholders such as investors. Deloitte recommends some areas that accelerator leaders should consider at the outset. These include identifying areas for potential disruption in the industry, determining whether there is a long-term commitment to building exponential business and scaling, and ensuring that the corporate leaders are supportive of digital transformation.

The hardest part of securing the long-term support of the C-Suite and board is persuading them that the risk of not following an innovative path and allocating the required resources is greater than the risk of doing so.

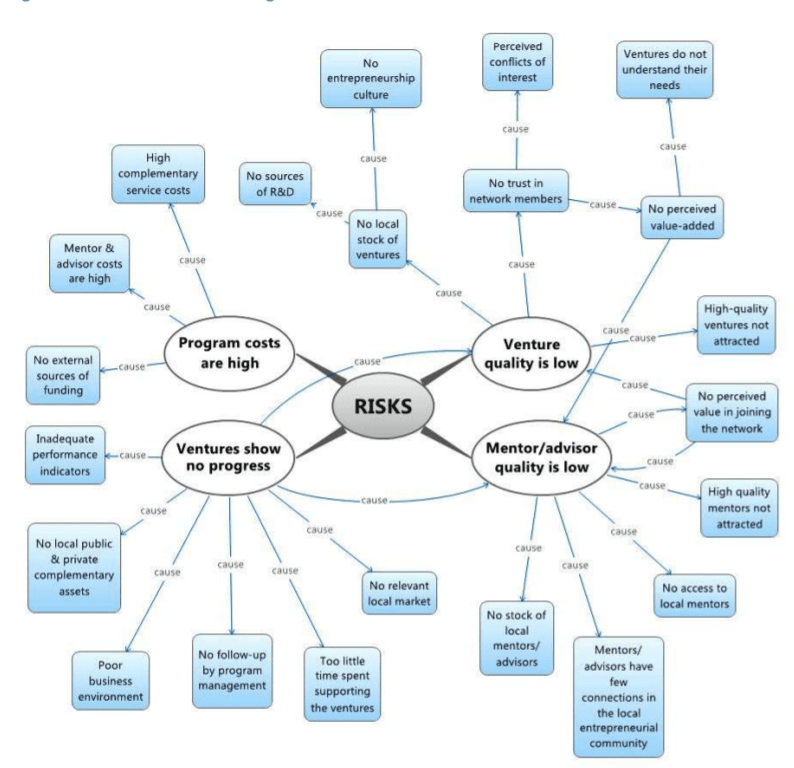

What’s scary about a corporate accelerator is that the risks are admittedly high. There are significant initial costs, and there is no immediate payoff. The quality of both startups and mentors can be low if either are poorly selected. Based on this graphic from the World Bank, few corporate boards that are protective of shareholders would jump at the chance to initiate an accelerator based on the risks.

Image Source: World Bank

But that’s the state of technology advancement in the digital age. High speed and high risk.

Kanbach and Stubner describe corporate accelerators as either integrated within the parent company as part of a specific business unit, such as digital or online business, or a specific department, such as innovation management, corporate strategy, or product development. The way that the accelerator is integrated determines the reporting line of the accelerator management team.

A separate accelerator removes the direct risk from the corporate coffers. It can act as a bridge between innovation and the corporation. It’s funding should be separate and anticipate high initial startup costs with a suitable timeline for returns. David McClure of 500 Startups warns, however, that too much accelerator independence could be detrimental if a company has many innovative activities ongoing within its structure. While some projects might have a short horizon and some a longer horizon, innovation efforts should be coordinated to avoid crossovers, expense, and missed synergies.

According to McClure, “[the corporation] might have an accelerator program, they might have an innovation program, they might have a direct investment program, they might have a VC arm and they might have acquisition, right? And I think all those should probably be coordinated.” That’s because innovation doesn’t start and end with the creation of a new product; a new product becomes part of the corporation’s core business.

Corporate Accelerator Metrics and KPIs

Pertinent to the independence and success of an accelerator, we look at how an accelerator’s progress can be measured over the short and long term. Data are key. Data can be the difference between the continued support of corporate leadership and the cessation of an accelerator. Data are also essential for cohort members to assess and document their progress in meaningful ways.

A study by the California Business Incubation Alliance from 2016 found that only 4 percent of corporate programs don’t track any performance metrics of their portfolio companies but almost 90 percent track financial and product milestones. Which data are tracked and reported depends on the focus of the accelerator governance.

- Financial: A focus on the financials is most likely to be demanded by the board and shareholders; therefore, Deloitte lists follow-on funding, the total value of portfolio companies, and the number of startups that have survived, exited, or folded (over each year or every three) as key performance indicators.

- Innovation Integration: For companies with a strategic focus on innovation integration, the number of joint efforts (co-development, partnering), the number of integrated technology or business models, business unit impact, additional business or revenue from startup, or number of startups that survived, exited, or folded can be used as KPIs.

- Public Relations: For marketing, the number of PR events, the amount of press coverage, the number of applications, and the number of participants can all show an uptick in ROI as a result of the accelerator.

It’s important for corporations to be transparent with their accelerator metrics to maintain trust and credibility and to ensure future high-quality applicants. Techstars provides an excellent example of transparency by listing every company it has ever funded.

For ideas on additional metrics for assessing startups, McClure suggests the following data for early-stage startups.

- Funding: Dollar amount or number of startups that raised capital after going through an accelerator program (or number that raised over a certain amount, for example, $250,000 to $500,000).

- Product: The change in functional milestones for minimum viable product (or improvement in selected features as measured by observed usage/qualitative survey/net promoter score).

- UX/Usage: The change in user reaction to a product measured by time on site, retention over time, a key conversion metric, or target goal behavior.

- Markets: The change in the number of active or registered users, or percentage conversion for a set of acquisition channels or campaigns.

- Revenue: The change in money generated, ideally based on the cost to acquire users.

- Team/hires: The change in team experience/skills acquired or hired during acceleration.

- Founder satisfaction: Simple qualitative survey of founder satisfaction with the program.

10. Post-accelerator: Assess Your Success

Post-program is the time to take stock and tweak the corporate accelerator process. While their role is to increase the rate and quality of learning over a short period, their true value comes from the long-term growth of relationships and networks. Here’s howto optimize these factors after the program ends.

The Importance of Post-program Startup Support

“Once an accelerator has developed over a number of years, the alumni network can be an important source for mentors and investors, as successful graduates are more likely to invest back into the community that supported them in the first place.”

— A Look Inside Accelerators, Bart Clarysse, Mike Wright and Jonas Van Hove, February 2015

Peter Relan, internet executive and creator of an early startup incubator, claims that 90 percent of accelerators and incubators will fail, or won’t provide a positive income, based on the rule of thumb that nine out of 10 startups fail. He lists the reasons for failure as too little mentorship, a lack of funding post-program, and a lack of development resources. All of this can be solved with post-program support.

The Power of Networks

Accelerators require long-term management. They improve over time, and their popularity depends on the quality of the selected applicants and mentors. The graduates from an accelerator join an alumni network, which broadens the accelerator and the corporation’s connections. Each new startup member through the program is a future alumnus who is often willing to re-invest time and money in the organization.

One suggestion from participants was that an online platform where program alumni can connect, share experiences, and access mentors they had met during the program would be helpful. In addition, graduates would like to have additional live training or online resources as a component of continued support services.

An ongoing network of alumni extends collaboration, increases knowledge-sharing and ensures the long term success of accelerators. Y Combinator’s unmatched success in this space is largely due to its extensive alumni network. There are even VC funds made up solely of Y Combinator alumni (Pioneer Fund, Orange Fund).

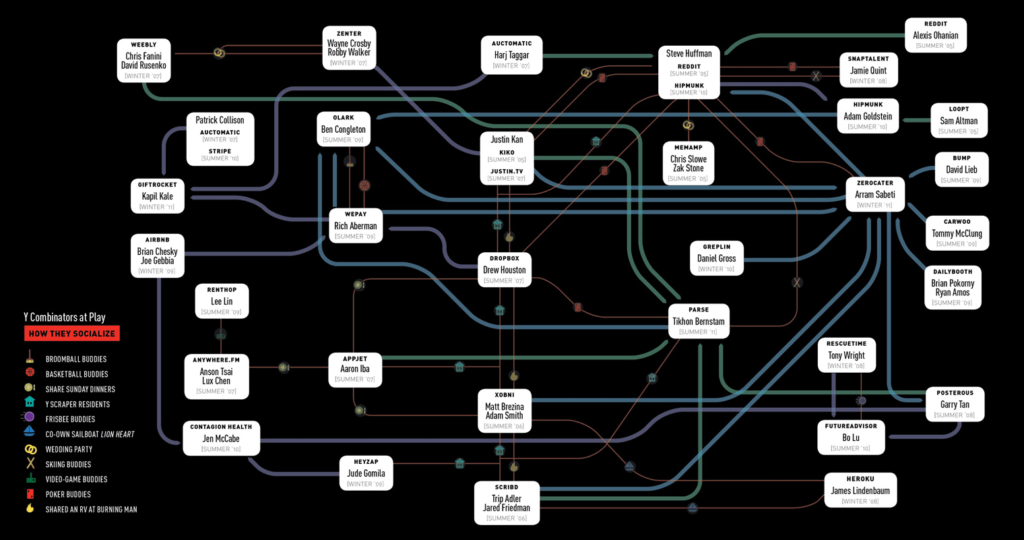

The infographic below shows how such networks play out in real life for Y Combinator.

Image Source: Fast Company

Support Programs

Relan implies that incubators are often more for show and PR purposes than they are real efforts with a long-term commitment to advancement. He also concludes that those startups who continue to have access to resources and support after they exit will have the best chance at survival.

From the startups’ perspective, according to an analysis by the I-DEV International in conjunction with the Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs (ANDE) and Agora Partnerships, a common complaint of incubator and accelerator alumni and a possible reason for failure is that programs did not provide enough support once the formal program came to an end. Some participants reported that they struggled to access the resources or ongoing support to translate plans into action.

The best accelerators provide outreach events and regular interactions for their alumni. According to Bridging the “Pioneer Gap”, the types of post-program support offered to entrepreneurs include:

- Public-relations opportunities.

- Connections with investors.

- Board participation.

- HR/recruitment support.

- Regional meetups.

- Online communities listing funding and promotion opportunities.

- Office space.

Further, these accelerators provide outreach to their alumni, in the form of events and regular interactions, to keep startups engaged with their program. This further strengthens the network effects outlined above.

“A demo day for alumni prior to the public pitches provides opportunities for the startups to get constructive feedback and engage the accelerator community,” wrote Thomas Kohler in a Harvard Business Review case study.

Founder Feedback

As with any project, there needs to be a review, and founder and mentor feedback is the bread and butter of any program that wants to achieve continuous improvement. In the case of Y Combinator, a survey is sent out to graduate companies requesting anonymous feedback. The information received is crucial to improving the results of subsequent projects, as stressed by Y Combinator’s Michael Siebel:

“One of the things we do is send a survey out to every company asking for anonymous feedback. You have no idea how much we read that. … That’s kind of the base for how Y Combinator changes. The things that founders think we need to improve are the things we figure out how to improve for the next batch.”

— Michael Siebel

Investing in Startups

After the accelerator program comes to an end, corporations may want to increase their involvement with promising firms. According to Kohler’s case study, there are five main ways a corporation can do that.

- Corporation supports pilot project: This is a faster, cheaper way to develop innovative solutions or products than trying to do so internally. It’s also likely to involve fewer risks for the core business. “Corporations may develop new products together with startups, explore market opportunities through startups, or solve business challenges via startups’ technology or talent,” Kohler wrote.

- Corporation becomes startup customer: As we’ve seen, the relationship that is built in the course of an accelerator program gives the startup an opportunity to land the corporate sponsor as an early customer. At the same time, interaction with multiple startups in its accelerator gives a corporation an opportunity to learn about different solutions to their business challenges. “Mutual benefits result if the startup wins the company as a high-profile customer, and the corporation finds a solution to its pain points,” Kohler wrote. “Working with a large corporation can be an important step for startups to test their product-market fit and scale their operations.”

- Corporation becomes distribution partner: A startup that can offer its products through its corporate accelerator sponsor can avoid the cost and effort of building out its own distribution network. Such channel partnerships can be mutually beneficial if they also solve a problem or create a new market for the corporation.

- Corporation invests in startup: For both parties, this can be a better deal than they’d be able to make separately. “Backing and supporting startups is beneficial for corporations as this provides them — at lower capital requirement and higher speed compared to internal R&D — with access to new markets and capabilities,” Kohler wrote. “At the same time, startups benefit from favorable terms relative to traditional sources of venture capital.”

- Corporation acquires startup: “Acquiring startups is a quick and impactful way to solve specific business problems and enter new markets,” wrote the authors of the 2001 Journal of Management paper “Resource complementarity in business combinations.” Accelerators allow a corporation to explore a variety of startups that could be acquisition targets, saving time that otherwise would have been devoted to scouting in the open market. Kohler noted that for startups, acquisition is an appealing exit strategy.