Communities of Practice

You will learn how to use communities of practice to capture, store and transmit the knowledge that exists in the blank space of an organization: the culture, the conversations, the workflow.

Communities of Practice (CoPs) – also known as learning networks, thematic groups, or tech clubs – are one of many tools that organizations are using to improve knowledge dissemination, facilitate learning, and stimulate creativity.

In this training, you will

- Learn what a community of practice (CoP) is.

- Learn the value of CoPs.

- Explore the types of CoPs.

- Design CoPs.

- Learn how CoPs facilitate knowledge capture and behavior and culture change.

- Explore calculating ROI from CoPs.

Skills that will be explored

About the Guide

Communities of Practice (CoPs) were called “The New Frontier” by Etienne C. Wenger and William M. Snyder, anthropologists and experts on CoPs and social engineering. Wenger and Snyder predicted in 2000 that CoPs, also known as learning networks or thematic groups, would be central to the learning activities of leading knowledge institutions. They were right.

The goals of CoPs are to build, protect, and retain corporate knowledge; communities also strive to promote learning among members. Members join a CoP voluntarily based on a shared interest and eventually move from a state of peripheral engagement to full participation. It is, therefore, this collective social practice that links individuals together across official organizational boundaries and departments – and beyond – to create the community.

CoPs are key tools used by companies to capture and store the knowledge that exists in the white space of an organization: the culture, the conversations, the workflow. Organizations such as the World Bank and American Management Systems, a high-technology and management consultancy firm, stand out for their fostering and leveraging of CoPs and the application of the resulting knowledge to their operations.

But many organizations are failing to provide the infrastructure to facilitate such communities. These structures are needed to capture institutional and individual knowledge, both of which are lost when employees leave an organization. This last point is important because tenure among Gen-Y and Gen-X workers at companies is shortening. The median tenure with an employer for Gen-Xers is now five years and for Gen-Yers is just two years, according to Payscale.com. With the rapid turnover of core staff and the competition for talent heating up, companies need to both maximize the talent and knowledge that they have in their communities and retain it.

Building Successful Communities of Practice

“Most of our intelligence doesn’t reside in our brain, it is externalized as our civilization, our culture. A standalone human is just an app”

— Francois Chollet, AI and deep learning researcher, Google, Quote via Twitter.

The Structure of Communities of Practice and the Role of Cultural and Behavioral ChangeThe first article in this series on CoPs defines CoPs and explains how companies and organizations can structure an environment conducive to community productivity. This article describes the components required to develop communities and explores how to stimulate the cultural change that is part of the process.

What Is a Community of Practice?

Communities of Practice (CoPs) – also known as learning networks, thematic groups, or tech clubs – are one of many tools that organizations are using to improve knowledge dissemination, facilitate learning, and stimulate creativity.

Etienne Wenger and Beverly Wenger-Trayner are anthropologists and experts on CoPs and social engineering. They describe a CoP as a group of people who collectively learn in an area of shared interest. For example, a group of researchers working on a similar problem are a CoP, as are a group of surgeons who are exploring a new technique or a group of first-time managers who are supporting each other as they gain confidence.

To qualify as a CoP, a group must have three components: the domain, the community, and the practice:

- First, the domain is exemplified by the common interest that distinguishes members from others – a group of programmers, for example, share the art of coding.

- Second, the community is represented by the sharing of information and the interaction among the community members on the matter of common interest.

- Lastly, the practice is the actual art of “doing,” or performing tasks that are related to and improved by the discussions within the community.

CoPs learn in different ways. They might problem solve and brainstorm, they might share information and seek out others who have more experience, they might share or reuse assets.

Membership in a CoP is voluntary, and members typically come and go and participate in other CoPs. This is advantageous to all involved because it extends the group’s diversity and the range of sources for ideas. The number of participants varies; however, in his book, “The Tipping Point,” Malcolm Gladwell documents several examples where companies or organizations have found that optimally efficient group sizes include 150 members or less.

Developing CoPs in the corporate environment is one way to achieve competitive advantage, because a community of like-minded, driven people can develop new ideas while building strong, collaborative relationships. CoPs are difficult to catalyze, however, because they are a byproduct of corporate culture. They develop organically in the right environment, but the difficulty lies in creating that environment and encouraging the desired behaviors that will capture and disseminate information within the community.

The Value of Cops for Organizations

Many organizations do a poor job at retaining both individual learning and incremental organizational knowledge. Staff development programs can use up valuable resources that many companies feel are better spent on R&D, for example. But the advantage of CoPs is that the learning they facilitate and the advancements they promote occur organically once the basic components are established.

Wenger and William M. Snyder, founding partner of Social Capital Group, recount the following CoP example in an article in the Harvard Business Review. At Hill’s Pet Nutrition facility in Richmond, Indiana, line technicians formed a group to help the company develop and retain technical expertise. The group meets weekly to discuss successes, frustrations, and challenges, and it has a “mayor” who keeps things on track and ensures the group has access to the right expertise when needed.

Throughout the course of its meetings, this community explored various concepts and ideas, generating a proposal to substitute pneumatic tubes for a conveyor belt that carried pet food kibbles to the packaging bin. After some back and forth between management and the community on the new concept, the company ultimately installed the new technology, which resulted in fewer downtimes and less pet food wasted during the packaging process.

If the right environment is created, then, learning should be a natural outcome of a community. This explains the value of CoPs for the corporate organization.

CoPs embody ambient learning, whereby learning occurs as a result of the environment. Khan Academy, for example, is a “one-to-many” broadcast model that lifts students to a certain proficiency level. CoPs build an environment where people of all skill levels learn simultaneously. There are no boundaries to the learning, and newcomers can participate immediately.

What process should an organization take to leverage and build CoPs?

Types of Communities of Practice

Fred Nickol, Managing Partner of Distance Consulting, LLC, suggests that there are two types of CoPs: self-organized and sponsored. The former can exist within an organization, and these CoPs are resistant to efforts to manage or control their direction. Members tend to come and go as the focus of the community changes and the community adapts. Sponsored CoPs are initiated and supported by management, and they are expected to produce measurable results that benefit the company. These communities receive resources as would cross-functional teams, but they have greater autonomy.

The World Bank Group creates internal CoPs called “Thematic Groups.” These groups work on difficult issues such as poverty, transportation, and infrastructure development. Hallmarks of these groups include: leaders and facilitators; a critical mass of active members; management support; resources; emphasis on problem-solving; focus on knowledge transfer and dissemination mechanisms; member trust and passion; etc.

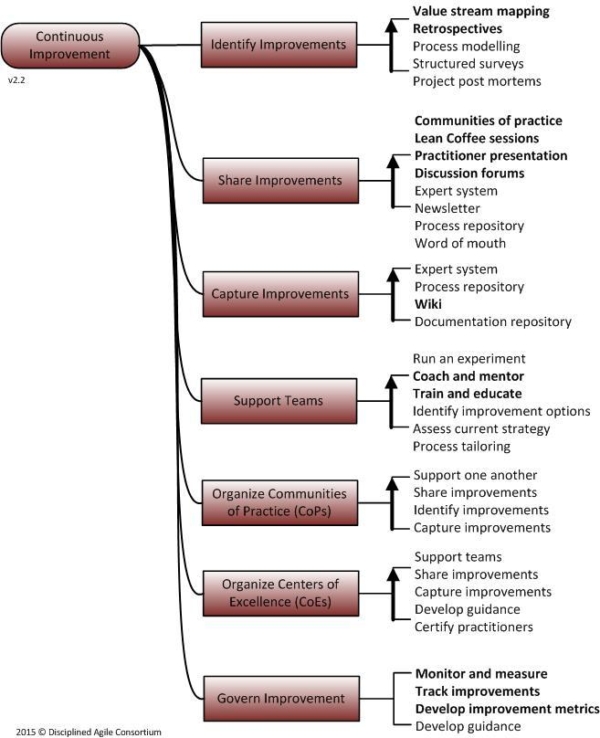

The Disciplined Agile Framework, created by the Digital Agile Consortium, is another example of a sponsored CoP and includes CoPs as part of a software development process using agile.

Source: Digital Agile Consortium

Designing Cops: From the Call to Action to the Feedback Loop

The creator of ZeroMQ, the late-Pieter Hintjens, identified guidelines for creating a community. The guidelines, broken down into 20 unique dimensions, are useful for organizations that want to create a culture conducive to CoPs without forcing the dynamics. While this resource is directed towards online communities, it is very easily applied to communities within organizations and communities that extend beyond organizational boundaries.

The dimensions include the following:

- “strong mission,” which is the stated reason for the group’s existence;

- “free entry,” which describes how easy it is for people to join the group;

- “transparency,” which is how openly and publicly decisions are made;

- “decentralization,” which is how widely the group is spread out; and

- “sense of humor” – i.e., how seriously the group takes itself.

Hintjens’ guide aligns closely with three core parameters that define a CoP: a call to action, frictionless collaboration, and a feedback loop.

The Call to Action

While CoPs develop organically once a shared goal becomes evident, it is helpful within an organization to consider what the desired type of community might look like in order to facilitate the creation of the right environment and culture.

Asking certain questions can indicate what changes an organization should make. “What goals, agenda, or mission will the community serve – and are these learning, membership, or assessment goals?” The answer(s) to this question would highlight what types of metrics an organization might use to monitor CoP activities. “Does the community’s technology infrastructure need to be integrated within broader information systems?” The answer to this question would help identify if the existing organizational infrastructure is going to stymie CoP efforts.

Once the right environment has been created, a well-constructed call to action can stimulate collaboration or learning. The call to action should be a simple, idealistic statement communicated through a channel that is popular among the target community audience. The call to action should speak to the early adopters of the community because these contributors will influence the initial community and bring it to critical mass.

For more on communication resources, read “Communication Technologies in Today’s Organizations.”

But crafting a simple, idealistic statement is easier than it sounds. Christina Xu, ethnographer and writer for Chrysaora Weekly, said the following about the call to action signal: “Whether it’s an invitation to an event, a call to action, a piece of art, or a literal flare, the signal is how you get the attention of the people you are trying to gather. Sometimes, it can also be a shibboleth to filter out who you don’t want, a way to indicate who the community is safe for and from.”

Xu emphasizes that the art of crafting a good signal requires marketing, communications, SEO, and media expertise. The primary concern is creating a compelling message so that the audience will connect on their own terms.

Frictionless Collaboration

CoPs should be fluid. The leaders in any community tend to be the most experienced participants but, in the interests of diversity, a cross-section in terms of experience is preferable to maximize the likelihood that new ideas will emerge. Those with experience could deter others from challenging their already established modes of operating. Also, in a more structured or sponsored community, membership terms could be structured so that the community is replenished with new people and ideas annually or semi-annually.

For communities to thrive, organizations should remove as much friction as possible. Friction occurs from a variety of sources, including communication tools, proximity, and organizational structure, but different tools can remove friction and facilitate interaction.

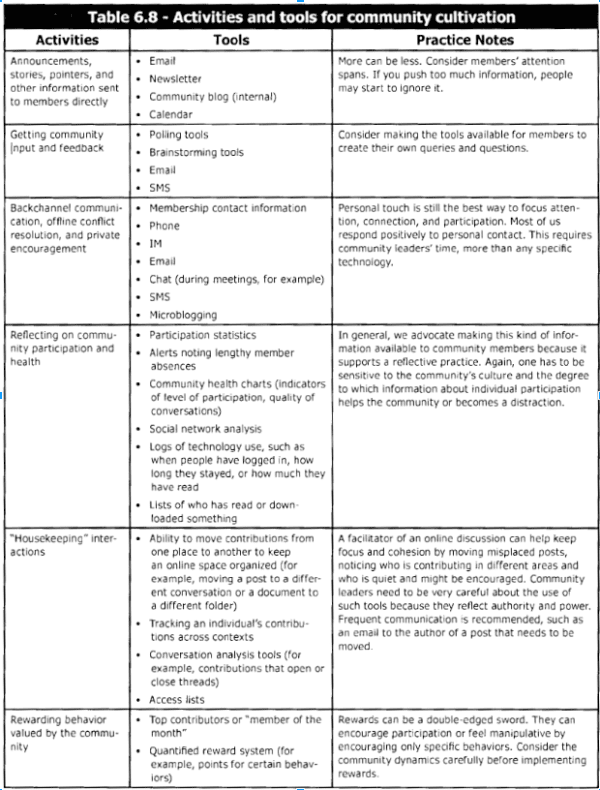

The table, below, shows which tools are best for achieving certain tasks such as communicating announcements, obtaining feedback from the community, and rewarding the community for contributing.

Source: Digital Habitats: Stewarding Technology for Communities, Etienne Wegner, Nancy White, John D. Smith, 2009

The Feedback Loop

A CoP is often first formed in an informal and ad hoc manner – a group may have a common area of learning interest and set up in-person or online meetings. If the CoP is worth pursuing, it will benefit from support mechanisms, such as discussion forums and communication channels, that an organization can provide to encourage collaboration and to collect information and feedback. Regular feedback that is incorporated into organizational change is an iterative feedback loop, and the resulting improvements to processes are the essence of the CoP.

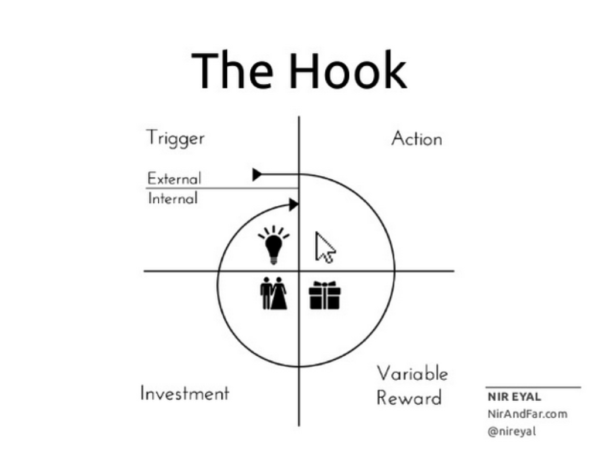

CoPs often have momentum in the beginning only to diminish over time or be altogether abandoned. To keep members enthusiastic, the infrastructure should provide ongoing content that participants find valuable and that attracts new members. By constantly pulling people back into the community, and by replenishing the community with new members, the CoP stands a greater chance of longevity.

Although focused on a community as a product, an article by GrowthHackers, a leading community platform, illustrates how to create a feedback loop that keeps members returning. Nir Eyal’s hook model uses internal and external triggers to nudge the audience into participating in and contributing to the community.

Source: CMXhub, 2015

Cops and Other Teams

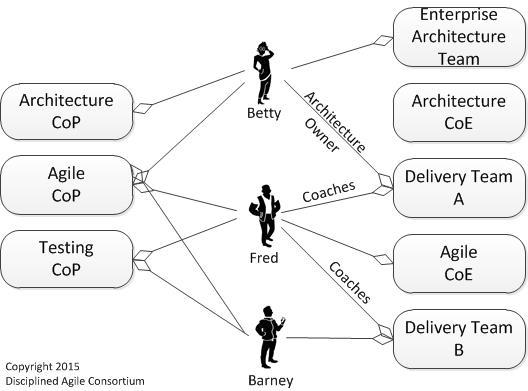

According to the Disciplined Agile Framework, introduced above, a more formal CoP might be initiated by an already existing Center of Excellence (CoE): a group of people with specialized skills and expertise who provide leadership and purposely disseminate that knowledge. A CoE is often funded for a specific knowledge purpose or to support a short-term organizational goal (such as an agile transformation). CoPs, because of their voluntary nature, often last much longer and may eventually replace a CoE.

The graphic, below, from the Disciplined Agile Consortium depicts the sometimes overlapping roles of employees in communities.

Source: Disciplined Agile Consortium

Behavior & Culture Change

A CoP will thrive in the right environment, but it requires a change in participant behavior that is, in turn, influenced by the environment. According to Rachel Happe, co-founder of The Community Roundtable, “In the initial stages of building a community, the ability to change behavior is the primary success metric. If you can orchestrate behavior change, you can fundamentally shift the economics of a process. Typically, this behavior change is also seen as valuable to community members, and that generates a pull effect that grows the community and normalizes the new behavior.”

Culture change is an even longer process than driving behavior change. According to Deepa Ray’s paper, “Life Cycle of CoPs,” communities go through five distinct and often difficult stages before they create significant value. These stages are the following:

- Potential: In the early stages, although members of a community might be aware of their shared or similar situations, there has yet to be an established shared practice.

- Coalescing: At this stage, community members begin to interact and to focus on a common focus and common goals.

- Maturing: During this period, the CoP sets standards, solidifies relationships, and outlines its agenda.

- Active: When shared practices develop and are integrated into group practice, a community enters its most productive stages.

- Dispersed: When a CoP begins dispersing and is no longer active, it functions largely as a knowledge repository at this stage.

These five stages also appear in an updated 2001 model by Patricia Gongla and Christine R. Rizzoto. The five stages are described slightly differently as “potential, building, engaged, active, and adaptive.” In the active and adaptive stages, according to the model, the community demonstrates the benefits of the new knowledge it has documented and uses that knowledge to obtain a competitive advantage.

If decision makers understand the slow nature of behavior and culture change, they will be more likely to commit to a long-term effort for community building. As the community matures, it is important that the iterative process be cumulative in terms of development so that knowledge is built and not destroyed. This requires maintaining the integrity of community members.

Moderation is also important. For a community to provide value, it must be focused and relevant. According to The Butler Group, for example, up to 30 percent of knowledge workers’ time is spent searching for data, which is a waste of time and resources. Moreover, according to the IDC, 50 percent of employees’ searches fail to find the relevant data. Poor moderation efforts lead to cluttered, irrelevant knowledge capture which in turn can lead to time-consuming and confusing information searches – accomplishing the exact opposite of what the community set out to do.

But moderation isn’t just cleaning out spam and banning users. It also consists of the careful management of contributions according to community members’ skill level. Allowing non-experts to contribute in a community can hamper its progress. Joel Spolsky, CEO and co-founder of Stack Overflow, a leading platform for coding experts, describes how the company excludes certain types of people from its platform. Smart technology identifies and prohibits non-experts from the site so that the quality of the content is maintained. We discuss Stack Overflow in more detail in the next article.

Knowledge Capture

With CoPs and organizational learning, the goal is to instill behaviors that will capture knowledge. In an article in the Harvard Business Review, “Balancing Act: How to Capture Knowledge Without Killing It,” John Seely Brown and Paul Duguid outline key issues surrounding knowledge capture. They recommend delaying knowledge capture until the group has matured and answers are clear – otherwise, the learning process can be suffocated by bureaucracy. The authors also emphasize that knowledge capture comes from the bottom up; experts in the community should be dictating what is shared, not top-level managers.

Brown and Duguid explain the knowledge capture process as follows:

“A rep submits a suggestion first to a local expert on the topic. Together, they refine the tip. It’s then submitted to a centralized review process, organized according to business units. Here reps and engineers again vet the tips, accepting some, rejecting others, eliminating duplicates, and calling in experts on the particular product line to resolve doubts and disputes. If a tip survives this process, it becomes available to reps around the world who have access to the tips database over the web. So, reps using the system know that the tips – and the database as a whole – are relevant, reliable, and probably not redundant.”

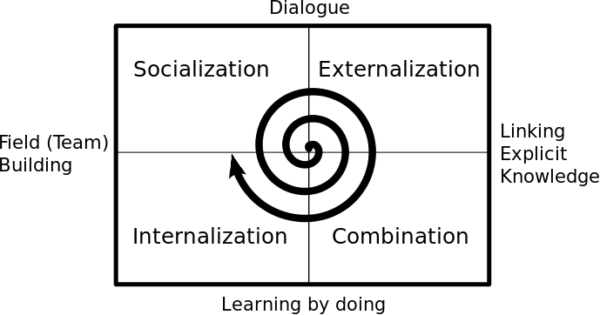

Eventually, feedback loops like the one in the diagram, below, can transform the culture of a company by creating an environment in which people support and challenge one other and build strong relationships.

Source: Wikimedia

Metrics and Management for Communities of Practice

“Meaningful learning in a community requires both participation and reification to be present and in interplay. Sharing artifacts without engaging in discussions and activities around them impairs the ability to negotiate the meaning of what is being shared.”

— Etienne Wenger, Digital Habitats

With any strategy that has difficult-to-quantify improvements as goals – for example, product innovations through better synergies and collaboration – finding concrete positive results is essential to sustaining the inflow of funding and resources. The same is true in the case of Communities of Practice (CoPs).

John Nelson, Project Manager for Dynamics Research Corporation, provides insights on integratingknowledge management with Lean Six Sigma, project management, business process management, and change management with organizations. Nelson studied the U.S. Army’s Center for Army Lessons Learned, which hosts over 60 CoPs.

To develop and obtain meaningful measurements, Nelson identified growth targets (such as membership and knowledge) and activity targets (such as participation) in benchmark communities. He found that one way to measure growth in a community is by member penetration, through which it is possible to measure the total knowledge transfer potential from the increased interactions among members (new and old).

Interactions monitored, for example, include online communications, external email exchanges, and phone discussions, as well as the number of documents uploaded or downloaded. These factors can be used to calculate a replies-to-discussion ratio. The level of vibrancy of any communications, and whether the communications are meeting community needs, are also salient metrics. So are more specific ratios, such as the page-visit-to-member ratio or the active participation rate (Knowledge + Discussions + Replies / Unique Visits), which can reveal if the organization is meeting the community’s needs.

However, although these measurements can assess the community’s success in attracting participation, they do not measure whether learning has actually occurred. For this, Nelson maps activities to objectives to determine the impact of the community knowledge management project on the organization. This is best illustrated through personalizing the data collected on community participation. The engagement metrics aren’t what encourages organizational buy in – it’s the connection to key organizational objectives.

In the case of the U.S. Army, proxy measures are often used to measure, for example, time or money saved. In Nelson’s study, one case reported a particularly powerful outcome of lives saved from CoP activities: “I used the quick notification of the Army Combat Helmet recall and forwarded to my unit supply sergeant to notify soldiers of my unit to check their helmets for the recalled stock numbers. No doubt that has saved lives.”

Hewlett-Packard has an internal CoP composed of the group’s North America-based product delivery consultants. The consultants hold monthly teleconferences to discuss the company’s High Availability software, which was designed to minimize computer downtime. Before the community convened, the consultants were isolated, but the collaboration has brought them together and helped them resolve common problems and learn from their counterparts. The community’s work has included standardizing sales of the product and its pricing, as well as formalizing the installation process. Participants do not have to participate in the meetings, and there is no strict agenda, but discussions that crop up are often valuable to many participants who might be experiencing similar issues.

Finally, with respect to measuring the effects of CoPs on operations and productivity – functions that are traditionally difficult to quantify, can be delayed, and are sometimes apparent only in the work of other teams and units – Wenger and Snyder suggest that the best way to assess value is by listening to members’ stories: “an analysis of stories found that the communities had saved the company $2 million to $5 million and increased revenue by more than $13 million in one year.” At Shell, community coordinators collect stories and publish them in newsletters and reports. American Management Systems organizes a yearly competition to identify the best stories.

Learning From External Online Communities

Engagement Metrics: Examples from GrowthHackers.com

GrowthHackers, an open online community for growth and marketing professionals, has specific metrics that it uses to measure improvements in the user experience. In determining what metrics are most appropriate, GrowthHackers emphasizes the importance of understanding the behaviors and dynamics of its audience.

The company is acutely aware of what it calls the “lurker” effect – whereby visitors benefit from content and community sites without ever logging in, creating an account, or participating. They read and watch the content, but don’t interacte with it (for example, by voting, commenting, or sharing). Jakob Nielsen, a Danish web usability consultant, called this the 90-9-1 rule for communities: only 1 percent of community members actively contribute, 9 percent minimally contribute, and 90 percent “lurk.”

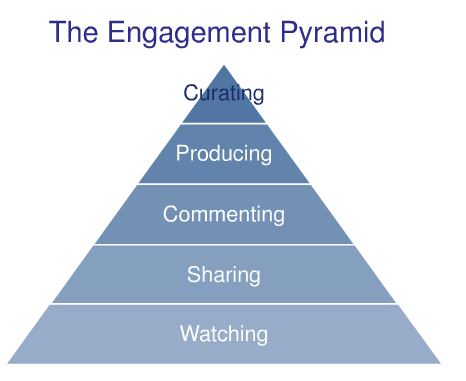

To encourage lurkers to become active participants, GrowthHackers tries to understand and meet the needs of each segment. Because the company wants to provide a learning and growth experience, it measures the quality of its supply-side content, not just the quantity. The company classifies its metrics using Charlene Li’s Engagement Pyramid, which refers to levels of visitor engagement.

Source: Social Media Modellen

Examples of metrics include new visitors and engaged time. More time engaged likely predicts higher engagement in the long term. Subscriptions to newsletters or created accounts is an obvious metric, but GrowthHackers also measures the percentage of visitors who comment or vote on at least one post over a period of a week or a month.

GrowthHackers measures retention by the percentage of visitors who visit the site and return within one week. The company also uses qualitative surveys and net promoter score – an index that measures the consumer’s willingness to recommend – with Qualaroo, a real-time customer decision analysis solution. Other metrics, designed to measure the quality of content, include votes per post, the length of time a post appears on the homepage, and the number of comments on a post.

GrowthHackers tests its framework with a High Tempo Testing (HTT) solution, which has a testing goal of three tests a week. Tracking the right metrics provides the impetus to improve core metrics and determine what changes worked.

Information Quality Signaling and Decentralized Moderation: Examples from Stack Exchange

Although not an internal system, Stack Exchange has effectively built a community – and subsequently captured knowledge – that nearly every programmer has used as a reference. This reference mechanism is what makes the community so powerful. A question asked and answered years ago can save a programmer significant time today. Joel Spolsky gives a fascinating talk on “The Cultural Anthropology of Stack Exchange,” which explains how the company analyzed users’ behaviors to design, build, and improve its platform.

The platform has also motivated contributors by: identifying the best experts within a specific domain and tracking their activity; awarding reputation points to users who showed their technical expertise and contributions; helping talented developers and contributors when they apply for positions.

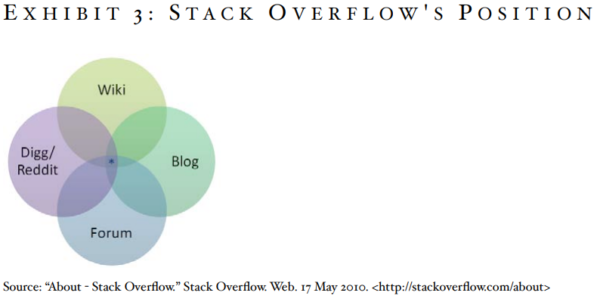

Stack Overflow, the flagship site of the Stack Exchange network, calls itself “a fusion of a wiki, blog, forum, and social rating website, emphasizing that it is a platform for the open and free exchange of information.”

Source: Social Media Modellen

Stack Overflow is an open platform where programmers can find answers for free and answer other users’ questions for upvotes and reputation purposes. It was originally created as an alternative to clunky and closed Q&A forums which were either algorithm-curated – with a set format question and unsatisfactory answers, such as Askjeeves.com – or human-curated.

In addition, Stack Overflow linked with social media to establish expert credibility. (Quora, for example, has accomplished this.)

Stack Exchange’s initial strategy was to eliminate six key Q&A shortcomings:

- sign-up scams where fake Q&A sites solicited contact information;

- incorrect answers;

- users’ inability to edit incorrect or incomplete responses;

- lack of comprehensive answers to complicated programming problems;

- inability to find multiple solutions to a question; and

- obsolete results.

To maintain the integrity and quality of the content on the platform, intelligent technology identified any potential members who were not experts and prevented them from contributing content.

The founders focused on SEO optimization of content because approximately 90 percent of traffic comes from Google searches. Questions submitted first acted like a search of the initial Q&A database. If there was no relevant content, the user would be one click away from submitting it as a question. This approach – a searchable, living Q&A function – has been incorporated into many organizations as a means of both capturing knowledge from internal CoPs and disseminating information to consumers.

Other building blocks which can be of particular value to company-wide systems were added to the strategy to assist in the discovery and maintenance of quality information:

- Voting: Visitor votes on answers are arranged by the number of votes received, and the best answers are displayed at the top. Users gain reputation points when others vote for their questions or answers.

- Tags: Every question is tagged, which helps direct questions to experts from a specific field to improve the quality and speed of responses. Users may also customize the Stack Overflow website by specifying tags of interest and filtering out uninteresting ones.

- Badges: Stack Overflow introduced the concept of badges. These awards, shown on the user’s profile, are given to users who consistently provide high-quality answers or ask popular and relevant questions.

- Karma and Bounties: Karma is a type of currency system that encourages and rewards participation. Users who earn enough karma enjoy special privileges: for example, only a user with sufficient karma can comment on answers and modify questions. Users win karma by selecting the correct and most relevant answer to their questions.

- Data Dump: Stack Overflow provides a “data dump,” which stores all the site’s user-generated content under a creative commons license. People can share and change content as long as it is correctly attributed to its author.

- Pre-search: Pre-search lays out questions to a user before the user can post a new question. This avoids multiple copies of the same question for better retrieval of relevant answers.

- Search Engine Optimization: The site uses various search engine optimization techniques: for example, the URL of a particular page on the site contains keywords from the corresponding topic.

- Critical Mass: Atwood and Spolsky promote Stack Overflow and direct traffic to the site using the initial community. Atwood answered questions from the outset so that quality answers were available.

- Performance: Built on a Microsoft software stack, Stack Overflow achieves high performance at a very low cost. Spolsky boasts that Stack Overflow’s performance is comparable to websites with similar traffic, but only requires one-tenth of the hardware.

Stack Exchange also helps to ensure quality by carefully managing the creation and growth of new communities.

The original Stack Overflow platform is now being expanded to more topics, and the model helps corporations determine where to allocate resources according to the lifespan of internal CoPs. Every new site created in the Stack Exchange network goes through a detailed review process consisting of six steps:

- Discussion: The Stack Exchange meta site provides a forum for discussing potential new ideas.

- Proposal: A public proposal is drafted and posted so that any member of the community can discuss the proposal and vote on it.

- Commitment: Two hundred users support the site.

- Private Beta: If the concept receives 100 percent commitment, committed members publicize and use the site in the private beta phase.

- Public Beta: A public period brings the site to its critical mass before launch.

- Graduation: The site is fully launched, based on multiple criteria such as the number of answered questions, new questions per day, and registered users.

Stack Overflow is perhaps the purest example of an organization that is nurturing technology advancement and learning by bringing together experts with diverse expertise and experience. Stack Overflow is leveraging its community as a platform provider and the communities that it supports with its technologies. The company’s successes and failures offer important guidance to organizations that are looking to better manage information quality and effectively moderate the flow of information among members in its community.

Calculating Roi From Communities of Practice.

Implementing new tools requires metrics and communication to succeed. A metric familiar to both employees and the c-suite alike is ROI. Return on investment, or ROI, is a battled-tested equation that is used throughout organizations. At its simplest, it measures the efficacy of an investment. For more transparent business areas, calculating ROI is fairly straightforward. This is not the case for communities of practice.

Communities provide value in many ways which aren’t immediately obvious to decision-makers. Customer satisfaction, for example, increases with a successful external community. But rather than attribute the increase to community, it’s often credited to the product team. A similar pattern can be seen with internal communities. Organizational learning and internal troubleshooting can be transformed through communities but the transformation is difficult to capture in business terms.

Communicating Community Value

Translating the complex value from communities into a clear, transparent return on investment is crucial to reap the benefits from this tool. Communities need support and time in order to reach their potential. This is achieved with clearly-communicated metrics.

This isn’t the time for a one-size-fits-all calculation — organizations need to tailor the process to their unique circumstance. A top-down approach, starting from the organization’s business goals ensures the correct focus and allows for the comparison of the community with the rest of the business’s activities.

Given this level of specificity, we’ve collected a variety of resources to help measure community ROI specific to your organization’s business goals. These resources are from the organizations that have deeply studied communities of practice.

How to Calculate the ROI of Online Communities – FeverBee

FeverBee has created an in-depth resource covering the entire ROI calculation process including the best data sources to look into and the common pitfalls leading to over or undervaluing a community. Click here to find this resource.

Marketer’s Guide to Customer Community ROI – Higher Logic

This resource aligns with the sales and marketing functions. Using external communities, business can see benefits like increased traffic to their website, increased leads, higher revenue-per-customer, and more. Click here to find this resource.

Research Brief: Calculating Community ROI – The Community Roundtable

The Community Roundtable’s research brief has refined a framework for calculating community ROI. Their approach revolves around community behavior of answering questions. Community provided answers can troubleshoot problems for customers, eliminate wasted time for employees and strengthen networks. Click here to find this resource.

Best Practices for Measuring the Return on Investment of Online Communities – Oracle

Created as a companion to the Oracle RightNow product, this resource has insights on specific community use cases including service and support, insights and innovation, loyalty, awareness, and commerce. Use the resource to learn about hundreds of metrics to look into alongside powerful equations for communicating ROI. Click here to find this resource.