Corporate Culture

You must build a culture that fosters productivity while balancing the tremendous social, political, environmental, economic, technical and legal challenges and changes that are present today. You will explore my thoughts from leading innovation at scale for 20 years. I also present what many in Silicon Valley consider to be “best practices” in developing culture.

In this training, you will

- Learn about the complexities of building a corporate culture that is inclusive and diverse.

- Learn about Silicon Valley’s “best practices” in culture.

- Explore examples of culture from Netflix, Facebook, Microsoft and Enron

- Explore stack ranking

- Learn how to change existing culture

Skills that will be explored

Author’s Note

This beginning of this article is different from all other HowDo content.

I would have loved to have started with a step-by step guide on Building a Corporate Culture that is similar to HowDo’s other guides. However, I struggle with corporate culture “best practice”, as those practices have created the systemic inequality that is the foundation of our current society and economy. This foundation needs to evolve. Therefore, best practice in corporate culture needs to evolve. Quickly.

Culture is hugely important when it comes to innovation. Unfortunately, corporate culture as a tool to building better companies is currently just theater. There is such inequality in society and corporate hierarchies that a discussion about corporate culture seems indulgent and ridiculous. A discussion on improving creativity, teamwork, and morale among workers requires long-term strategy. CEOs of large companies are often threatened with their jobs if they pursue a long-term strategies. The CEO’s bosses – shareholders – prefer short-term tactics that ensure dividends and buybacks. Until we fix the root cause of culture failure (short-term focus on shareholder value), any action to improve culture is merely posturing.

I believe that we have come to a point where the American worker is a commodity. Few are valued, and most are cast aside when necessary because there are plenty more available where that came from. The misery is evident throughout the social strata; from factory floor workers who are forced to accept abysmal working conditions, teachers who must moonlight as Uber drivers, to cardiac-prone executives who think that meeting quarterly earnings is worth an 80-hour week and the plushest corner office.

Assuming that a company is seeking to create and to build a culture of living wages, I suggest five basic principles:

- Pay staff a living wage

- Show respect

- Value diversity and inclusion

- Use data

- Be customer-obsessed

That’s it. It’s not rocket science, and it should be intuitive. But the problem is that investors control the companies, which means that near-term profits rule over long-term evolution. Of course, a certain culture can improve profits, but it’s usually at the cost of something that people consider more important, such as their health, happiness, time with family and the foundation of the community and environment around them. Thus, such cultures are not sustainable over the long term.

Amazon developed a culture that assured them unbelievable success. But even for Amazon, the chicken’s are starting to come home to roost.

Click on “About Us,” on Amazon’s website, and here’s what you’ll see”

“Amazon is guided by four principles: customer obsession rather than competitor focus, passion for invention, commitment to operational excellence, and long-term thinking.”

Amazon is driven by the bottom line, as are all corporate enterprises, and it has been revolutionary in its efforts. But this power comes at what cost to its workers? Amazon’s vice president of cloud computing, Tim Bray, in May 2020, stated that “Amazon treats the humans in the warehouses as fungible units of pick-and-pack potential.” He resigned after witnessing the firing of whistleblowers who were exposing the fear of warehouse employees working under the threat of COVID-19.

Thus, to underscore my earlier point. Until corporate America is in a healthier place and not purely driven by profits, a discussion on culture can only be about exploitation.

How It All Went Wrong

When Patty McCord wrote Netflix’s culture deck “Freedom & Responsibility”, she cemented in the minds of Silicon Valley executives that technology companies have to be inherently staffed by the best for their needs at the time. According to McCord:

“Adequate performance gets a generous severance package. We’re a team, not a family. We’re like a pro sports team, not a kid’s recreational team. Netflix leaders hire, develop, and cut smartly, so we have stars in every position.”

— Patty McCord

McCord and Netflix managers use what they call the “Keeper Test” where they ask: “Which of my people, if they told me they were leaving for a similar job at a peer company, would I fight hard to keep at Netflix?” Those that don’t make the list get generous severance packages to make room for a perfect fit for the role.

Netflix is like the NBA, and NBA players who aren’t the best are let go. I experienced the Netfflix culture firsthand. I interviewed with Netflix, and I even got the job as Director of Innovation. My last round of interviews was with Patty McCord, and she began the interview by saying rather dramatically that she had just come from letting seven people go.

“Oh my God, that’s terrible,” I responded. “I’m so sorry. Was the team not doing well?”

“No. Our needs changed.” she said, abruptly.

“Well, why not just retrain them?” I asked.

“Because we can’t retrain them fast enough. It’s faster just to hire someone who knows what we need now.”

I turned down the job to stay at PayPal.

Sheryl Sandberg, the COO of Facebook, said that Patty McCord’s culture deck was the most important thing to come out of Silicon Valley. In the ensuing months, 13 million people read that culture deck. The deck, unintentionally, pointed to a homogenous workforce filled with the best that the millennial Harvard-MIT elite could muster. It changed everything, and all of Silicon Valley agreed that its tech companies should be filled exclusively with top performers. Around the same time, 2011, Walter Isaccson’s biography on Steve Jobs was released. This book gave permission for all Steve Jobs wannabes in Silicon Valley to become raging assholes overnight. And so the culture of homogenized tech was born.

As we look at the future, the gig economy is front and center for most jobs and for most job categories. That’s only going to grow. And, in the meantime, technology is getting more complicated; that is, if you’re an actual technologist. Emerging technology companies with real potential are few and far between. So, the salaries, the benefits, the stocks, all those things that go along with a high-performance culture are becoming more and more polarized among demographics, among geographies, among teams, among companies.

Take Amazon as an example. The office culture of the warehouse is very different from the office culture of the machine learning teams. The machine learning teams have different cultures across the different disciplines of machine learning and the various categories or services or products to which machine learning is being applied. If you have a team of MBAs, the culture will be dramatically different then if you have a team that didn’t graduate high school. Education changes the culture, geography changes the culture, everything changes the culture.

The Complexities of Corporate Culture

Corporate culture is plagued by two clearly opposing forces. One is the brute force reality of the current market that demands high-level operations at all times; otherwise, you fall behind. Many companies are buoyed by great cultures now, but they are not going to survive when up against the Amazons of the world. In 1964, the average tenure of companies on the S&P 500 was 33 years. In 2016, the average was 24 years, and it is forecast to shrink to just 12 years by 2027, according to Innosight’s biennial corporate longevity forecast.

But the second force is that great cultures are possible, and they have led to incredible breakthroughs. While the cultures of Amazon, Facebook, Netflix, and Microsoft are easy to criticize, their success in terms of corporate evolution cannot be denied.

If a company has a successful culture today, I would wager that there are one of three things going on. The first is that it could be a monopoly. In this case, the company has past maturity, and is slowly on the decline while trying to extract as much money for Wall Street and CEOs as possible. There is enough cash to go round, and no one is rocking the boat—for now, culturally, things are stable.

The second thing that could be the case is that the company is a super early-stage startup financed by sociopaths who don’t care about employee well-being or the well-being of the product. The financiers are in it to make their [LPs] happy so that they can raise more money and get more fees. Startups have great cultures. Everyone working there is on an equal footing because nobody knows what they are doing. The whole team pitches in and gives their best intensively, often to a good end. However, 90 percent of startups fail.

The third scenario for a great culture could be found in a niche boutique retailer, or a small brand with a high degree of specialization and differentiation. In other words, there is a unique selling product with a defensible market position.

Why do these three scenarios work culture-wise? The reason is that none of these scenarios involve the need for hyper-performance. The need for hyper-performance, or scaling, changes the stress associated with the functioning of the teams. When a company grows to a certain point, people start to experience imbalance in their lives.

The Work-Life Balance Myth

Many Silicon Valley companies go to great lengths to ensure hyper-performance from their employees. Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Citigroup, JP Morgan, Cleary Gottlieb and Kirkland & Ellis, Unilever, Deloitte, Uber, LinkedIn, Intel, Ebay, Yahoo, Netflix, Salesforce, Spotify, Time Warner, and Snapchat all offer oocyte cryopreservation—egg freezing—to their female executives. Disguised as the ultimate perk, it merely extends the productivity horizon and shelf life of their female performers. In the meantime, all employees, egg incubators or no, are expected to give their all, sacrifice time with loved ones, and cast aside their own mental states for the pursuit of profits. This is the work-balance myth.

It’s a well-documented phenomenon that the video game industry constantly uses people until they’re burnt out and they disappear, both on the supply and the demand side. But it’s such an attractive industry because it’s fun, trendy, carries prestige, and there’s lots of money and perks.

The companies that are perceived to have good cultures are filled by type-A personalities who are willing to forgo normal life. They also tend to be young and full of optimism. How many 65-year-old product managers do you see? VPs of products? These people quickly move out of the sector. I did.

My experience as an innovation and product manager was not something I care to repeat. I wish I had been better equipped to deal with corporate culture. I had to make really tough decisions on the spot with my team. I lost so much sleep. I gained so much weight. I needed therapy sessions and had emotional breakdowns because I cared deeply about the people I was trying to manage. Some of whom were not the right fit, some were outrageous assholes, and some were just the best people I’ve ever met in my entire life, and I’m friends with them until this day.

I was trying to relate to people who were just trying to protect their jobs and who knew I could take that job away. Meanwhile I was trying to achieve the goals set by executives who were waiting for a good reason to snipe my team’s paychecks. I had to justify all of these things all the time. It was impossible to balance and emotionally punishing.

Corporate culture is glamorized. The stories where teams are flown to cool exotic locations may look like opulence, and sometimes they are—WeWork was a great example of ridiculous excess for a product that didn’t need to exist. But what people miss is that these stunts are moves of desperation because their teams are on the verge of quitting.

Every time I’ve resorted to a morale-building splurge for my team, it’s because they’re burnt out, and if I hadn’t done something they would have found a better job; one with less stress and more meaning. Because once you get in the middle of that stress, there’s absolutely nothing that you want to do other than escape that stress.

I’ve been in meetings where executives have staunchly advocated to find a location for operations where there is no union. Let’s not deal with collective bargaining rights, workers’ rights, healthcare, the law, OSHA safety precautions, reasonable working hours, or the ability to take time off. Basically, these companies don’t want to deal with the fact that they have to employ people.

These companies are not investing in the future; they are investing in themselves. That’s why stock buy-backs are at an all-time high, because the culture of executives is that they should give themselves as big a bonus as possible based on the most reliable way of paying Wall Street.

Wall Street’s Trickle Down

Wall Street expectations are around 7% growth annually. Most companies can’t grow their revenue at 7%, so they boost their value to remain attractive to investors by buying back their stock. Supposedly, this is also a sign of confidence and an indicator that management considers growth to be imminent. That’s the culture of Wall Street. That’s the culture of the CEOs. Meanwhile, Wall Street and investors hold all the strings and the livelihoods of the board and the executives.

So, if we are to stop our gradual economic decline and build a culture where employees are moderately comfortable, adequately educated, not living in food deserts, and able to earnestly focus on a vocation, Wall Street must stop taking the money of corporations, and CEOs must stop lying to their employees and claiming to nurture a culture for the future.

Venture capitalists are much the same as Wall Street investors. A startup’s mission will end at the first round if they are not doing well. No profit? Your asset will be up for sale, and you will get nothing. Only a fraction of companies, perhaps 5% of companies who start, might receive venture capital. Ninety-seven percent of those fail. Only 60% of the investments will succeed. With a 60% failure rate, investors are not going to invest equally among all of them; they have to prioritize among those that have the highest probability for return.

A startup culture might be great at the beginning and in the first couple of years, but it will all turn to nought unless it is a stellar standout. But as that startup scales, it will follow the path of most success stories. If you are an executive at the top, you’re golden, but if you’re a warehouse worker at the bottom, you’re screwed.

So, to discuss internal culture as a way to innovate is merely posturing. The reality is that executives, most often the COO, CFO, CEO, and CTO, are all incentivized by Wall Street. They are concerned only with short-term profits, which is not conducive to a culture of evolution. Until that changes, the decline in corporate culture will continue. While workers are so desperate that they must accept whatever they can get, a discussion on corporate culture seems ridiculous. Either we make more, better companies, or we just need to admit that culture is a moot point.

To get anywhere, we must fix the culture of companies and help companies actually grow—grow under their own weight, grow with their teams, grow with the life around them, grow within their communities, and help their communities to grow. “Help families in need” is the only cultural pillar that really makes sense for every company, but we’re far from that.

Change the Incentives, Change the System

The answer, in my opinion, is to build better companies that don’t need external capital, that solve real market problems, that have long-term strategies with long-term capital plans and capital allocation. Such companies will be solid and possess the potential to evolve and contribute value.

Foundationally, that takes changing the incentive system.

Right now, a very small number of people get rich and everyone else gets the crumbs. We have to change the paradigm. If the incentives change, culture will adjust and become bespoke to the solution.

Muller’s Ratchet and Diversity

Paying workers a living wage and respect are two pillars of culture that shouldn’t require explanation. Valuing diversity is equally valuable and essential to evolution.

Muller’s ratchet describes a process whereby a biome is exclusively reproducing asexually and inherently producing more flaws. Even in asexual creatures, the offspring that have the highest probability of survival are those that are genetically different, not those that are genetically similar. In sexual reproduction, that’s the whole point. You mix the DNA of two individuals, and you produce something that is de-risked for the future.

If we try to build culture around a group of homogenous Harvard Business School graduates or McKinsey models, we are inherently predisposing the future to bias. What we should be doing is trying to solve problems in real time with diverse individuals who deserve to be on a team. And the work must be done in an environment where there is respect, tolerance, understanding, diversity, inclusion, cultural sensitivity, and communication.

In conclusion, I would go so far as to say that culture is the absence of something more than it is the presence of something. It is the absence of a manager who threatens you if you don’t perform as expected, it is the absence of worry that you must make decisions based on the need for short-term profit. It is the absence of the need to please shareholders rather than optimize the potential of what you have.

Change is upon us in so many ways, and I hope the time will come when culture can truly be the engine for creative and evolutionary companies, not just Wall Street.

* * * END AUTHOR’S NOTE * * *

Corporate Culture: the Research So Far

Because culture is such an important topic and a critical component of companies’ machinations today, I realize that it should not be dismissed. The following is a collection of the data, theories, and knowledge that I have gathered over the years before the economic and social context took a turn for the worse. I would like to tell you that I have the answers and the tools. But all I can suggest is that we start a conversation that includes the data and information that I present.

In that regard, I welcome your opinions and experiences as readers to build a forum upon which we might find a better way.

How Big a Factor Is Culture in Firm Performance?

Scholarly interest in the impact of culture on organizations is well documented. In 1992, Harvard Business School Professors John P. Kotter and James L. Heskett studied the corporate cultures of 200 companies and how each company’s culture affected their long-term economic performance.

The researchers also wrote a book chronicling their findings called, “Corporate Culture and Performance,” which concluded that strong corporate cultures with strong financial results “highly value employees, customers, and owners, and that those cultures encourage leadership from everyone in the firm.” Firms that were studied include Hewlett-Packard, Xerox, ICI, Nissan, and First Chicago.

In strong corporate cultures, if customers demand a change, say Kotter and Heskett, “the organization’s culture is such that people are forced to change their practices to meet the new needs. Also, anyone within the organization is empowered to do so.”

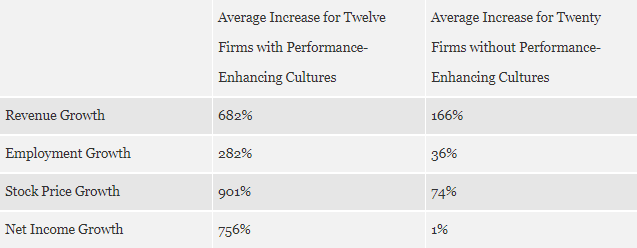

The table below is extracted from the book. It shows the difference in performance for 12 companies with a performance-enhancing culture and 20 without a performance-enhancing culture in areas such as revenue and stock price. The differences are staggering.

Image Source: Kotter and Heskett, 1992

What Defines Corporate Culture?

Corporate culture is the summation of all the interactions that make up a company. Think of it as a family. Some families are loud, members speak their mind without holding back, and frequent conflicts are common. Other families are quiet, they communicate as little as possible, and conflicts are avoided at all costs. It’s very difficult to make a quiet family act like a loud family, it’s against their nature and all they hold dear. It’s also very hard to change an established corporate culture.

Kotter and Heskett refer to a “performance-enhancing culture,” which they describe as one that highly values employees, customers, and owners and empowers all of its employees to become leaders. Steve Blank, a Silicon Valley entrepreneur, author, and professor, uses the term “innovation culture,” which is “a large company with a unified purpose that can move with speed, agility, and passion.”

Ex-Netflix chief talent officer Patty Mccord defines culture as:

“the stories people tell. It’s the way people operate when no one’s looking. It’s the values that you hold dear, that you know your colleagues do [as well]. It’s the expectations of how people are going to behave, and what gets punished and what gets rewarded.”

— Patty McCord

A firm’s culture defines to what extent it serves the customer well, is doing what it is capable of, and is cognizant of its competition. A fair assessment of a corporate culture can identify gaps and show ways to manage that competition bearing in mind the macro trends in the business and natural environment.

As Amazon has shown, embedding a culture is a huge component of business strategy. Culture will affect your company’s approach to the market; the how, when, and why of actions. If actions become second nature by becoming culturally ingrained, everyone involved with that culture does the “right thing” instinctively. Culture is powerful.

Many will agree that culture is the primary barrier when shifting from a traditional organization to a learning organization. The transition requires adopting new norms and letting go of old ones, something that is difficult and uncomfortable.

Jeff Bezos, CEO of Amazon, knows that if the culture is right, problems in the business process can be quickly solved. If the culture is wrong, the opposite is the case. That’s why Amazon places such emphasis on its customer-first and data-driven culture. Both of these cultural pillars are crucial.

Why Is Culture The Reason That Innovation Often Fails?

Culture, not processes, are the reason that most businesses fail. In a startup, under a “lean” model, small teams work independently and quickly to solve problems. This works for a startup where everyone on the team is in the same boat and working together intensely toward the same goal. The culture works.

But what happens when the startup grows, scales, is acquired, or joins a larger corporation. The added stress changes the culture. First, not everyone can be on the “cool” team, and jealousy rears its ugly head. Second, the cool team threatens to change the way the company works, which creates uncertainty and fear. You can’t suddenly change the way a warehouse functions, for example. There are protocols to follow, safety rules, processes set in stone.

Thus, there are almost two extremes in business culture—there is either continuous change and evolution at a consistent pace, such as a startup or an anomaly like Amazon—or the culture is static. Most businesses are in the static world. If you have something that is moving fast and breaking under the lean process, and you try to inject it back into an established culture, most of the time, the body rejects the organ. This is the number one reason for corporate innovation failure.

Microsoft is a focus because it has come full circle in its cultural journey. From its emergence as a jean-clad team of motivated comrades, it became bloated by bureaucracy. At the same time, in-fighting caused its innovation and products to fail, and Microsoft ultimately became a laggard experiencing a “lost decade” as far as market superiority is concerned beginning in 2000.

Although organizational culture is notoriously difficult to change, at the same time, it is in a constant state of change. The matter that makes up the organization is ephemeral. We see form and automatically assume permanence and stability. Even our own human body is in a constant state of change. Here’s a quote from Steve Grand, British computer scientist, roboticist, and author of “Creation: Life and How to Make It.”

Transitioning from a Traditional Organization to a Learning Organization

“Not a single atom that is in your body today was there when that event took place (your birth). Every bit of you has been replaced many times over (which is why you eat, of course). You are not even the same shape as you were then. The point is that you are like a cloud: something that persists over long periods, while simultaneously being in flux. Matter flows from place to place and momentarily comes together to be you. Whatever you are, therefore, you are not the stuff of which you are made. If that doesn’t make the hair stand up on the back of your neck, read it again until it does, because it is important.”

— Steve Grand

The same can be said for evolutionary businesses. A constant influx of new processes, technology, and people help these organizations solve the problems of the present and future, not the past. Things that no longer solve the business’ problems are replaced.

To change your company, you have to change your culture in a certain way. To change your culture, you have to change your people. That is expensive. Amazon’s internal capabilities, based on its people, allow it to build things very quickly. Google has the same capabilities, as does Facebook and many other tech companies. But this is because they have the wherewithal: capital.

If you don’t have the capabilities then your time to build a project is going to be longer, particularly if you have a quality product. To build new things, you need to hire people who can test and learn, not maintenance people. You need to hire people who aren’t simply operators but are abstract thinkers and problem solvers. You need to hire people who develop and design in totally new ways for totally new demographics. That is a costly proposition.

Without that investment, you are not going to be able to produce the same quality of product in the same time, and you will fall further behind. Thus, you have to fix the root problem which is your capabilities, your culture, and your team. Acquisition is a great way to innovate. The biggest and best companies acquire top employees by advertising a dynamic culture. Top performers are attracted to this environment because they want to solve hard problems all the time with like-minded peers. The problem here is that most companies fail to consider diversity and inclusion, and their talent pool becomes homogenized.

Data’s Role in Culture Change

It takes a unique and expensive set of skills to change and evolve every day based on data. Most companies change in a traditional way; they simply press repeat on proven marketing or branding tactics . But the growth button is evolving every day in technology, and it’s hard to get your finger on it. The divergence between growth based on data and growth based on tradition is why the tech companies are outperforming many industries.

Satya Nadella, CEO of Microsoft gave his insights on the topic of corporate innovation in an interview with The David Rubenstein Show.

The interesting thing (that) happens when a company becomes successful is this beautiful virtuous cycle that gets created between your concept or product, your capability and your culture. Right? You really have all these three things fall into gear and they’re working super well. But then what happens is the concept that made you successful runs out of gas. It’s not growing anymore. You now need new capability. And in order to have that new capability you need a culture that allows you to grow that new capability. Right?

Our server business was growing strong double digits. It was a high margin business. You look around on the other side of the lake, there is a very low margin business called the cloud. People were looking and saying: “Why would we do that when we have such an amazing fast-growing high margin business?” That I think is the challenge. So to be able to see these secular trends long before they become conventional wisdom, change your business model, change your technology, and change the product is the challenge of business.

You know in tech it’s unforgiving. But quite frankly now that tech is part of every business, I think all of us have to deal with it.

— Satya Nadella

Companies like Amazon use data—customer data—to identify trends. This customer focus, combined with the knowledge that Amazon amasses from its platforms and touchpoints, ensures that Amazon has the greatest opportunity to be right. Evolution becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Which is why Jeff Bezos emphasizes again and again that “it is always Day 1 at Amazon,”— that the company is always learning and changing. Want to find out what happens on Day 2? Check out Bezos’ 2017 letter to shareholders. The letter reads, “Day 2 is stasis. Followed by irrelevance. Followed by excruciating, painful decline. Followed by death. And that is why it is always Day 1.”

So, Amazon’s ethos is to always be seeking change or die a slow and painful death. Amazon shows us why data needs to be at the root of corporate culture.

Inclusive Learning and Data

Inclusive learning means that you have a culture that openly shares data and knowledge. This levels the power playing field. In this environment, the person with the best data informs what decision should be made rather than the person with the most power, clout, or the loudest voice.

Exclusive learning, on the other hand, means that only a select few—perhaps only those on the project team—learn the new information. Even if there is a delay in the release of information so that, over time, the field is level, you are still creating temporary information asymmetry that can create fear or anxiety.

I’m not advocating that you should share everything all the time—far from it. My point is that information asymmetry creates anxiety. This fear felt by the team is totally normal. Change introduces fear, often inherently, so it is best to address this fear head on with transparency and consistent timelines. Communicate with the team. Yes, things are changing. Here’s the process we’re going through. Here’s, when we’ll know the results. Here’s when you’ll know the results. Here’s why there’s a delay. Explain any need for confidentiality for legal or investor-related concerns.

Data’s Role in Consensus-building

When changing from a traditional organization to a learning organization, the process is one of change management. First, you need consensus from the people at the top.

Data is a great way to build consensus. Using data, you can identify and understand your customer, your competition, and your context. With that knowledge, you can tell a story that backs up your strategy and builds consensus. Here is how our competition is solving the customer’s needs, here is how we are solving the customer’s needs, here’s our plan for success.

If getting buy in at the top is a challenge, don’t dismiss the power of the bottom. Most organizations are a pyramid in shape, unfortunately. If you can build a coalition of people along the bottom of the pyramid, and that is not meant in the pejorative sense, you can build a consensus that leadership will find it hard to ignore.

Here is a process that I followed when seeking support for a venture:

- Gather data and share it

- Have a vigorous conversation to get alignment

- Share that common narrative with the rest of the organization

- Use your culture carriers to further your cause and build buy-in

Culture Carriers

What is a culture carrier? Culture carriers should be in almost every change management paradigm. Culture carriers are those people who empathize with your mission and the data that you have to legitimize your cause. These individuals act as messengers for your cause between the silos and groups in an organization. They carry new ideas from one group to another, and then carry feedback from the target group to the originating group. These representatives are trusted by all, and they break down the silos by inviting people in for vigorous debate.

Culture carriers contribute to the daily workflow by bringing their department’s data to the table. While the connections may at first be tenuous—they will become increasingly clear. For example, culture carriers expose issues with direct insights and knowledge. For example, the cost of janitorial staff and supplies could be excessive and detracting from another part of the business. A culture carrier might bring this and other issues to light.

Culture and the Value Chain

When examining your culture, remember that culture is what drives what employees do when management is not around. I’ve found more often than not that—regardless of what management says—if the right people in the places are aligned with the customer, the company is in a good place. Thus, you need your culture to be aligned with your value chain.

However, as I have suggested, it’s rare that people self-servingly align their personal interests with the long-term interests of the business. Doing so does not make sense for most people, who may not be around in that firm in five years. Culture is the intangible tool that can align these disparate motivations—or create significant friction.

Consider the politics in your organization? Is there a strict hierarchy? Is there ignorance that is inspiring fear that, in turn, leads to inaction? Or, on the other end of the spectrum, do you have a bunch of people hacking stuff together and running experiments all the time? Both are potentially viable ways of running a company, but one has a measurable pattern that can be scaled and managed to produce more reliable results than people fighting for their own political and personal interests.

The ultimate goal is to align individual motivation with relevant data and facts that drive improved decision making—lower costs, newer products, different services, new approaches to old problems. If you can get to this stage, you’ve done a great job of creating structural incentives. These incentives will support the behaviors that will advance your strategy, even when management is not around.

For the purposes of your analysis, the culture that is most pervasive in your organization should be the focus. The executive culture is probably different from the managerial culture, which is probably different from the operational culture. Teams in the same discipline in the same office even have their own culture.

Look at the culture that is a result of the legacy business that is driving decisions—not your company’s mission statement. I’ve found that mission statements make great wall art, but don’t do much for strategy.

Enron, for example, had a wonderful list of corporate values: Respect, Integrity, Communication, and Excellence. Each had their own detailed description. For example, respect was defined as the following: “We treat others as we would like to be treated ourselves … We do not tolerate abusive or disrespectful treatment. Ruthlessness, callousness, and arrogance don’t belong here.”

Enron is a glaring example that written values and mission statements, while an important part of creating a corporate identity, are meaningless without culture creation and management. Enron’s culture was well known for its lavish excesses that persisted right up until the firm’s bankruptcy. Neela Banerjee, David Barboza, and Audrey Warren reported in-depth on Enron’s unchecked lavish spending—a $1.5 million-dollar Christmas party at Enron Field and Waterford crystal gifts for Secretaries day, for example —which created a culture that ultimately led to the company’s downfall.

A true culture can be explored by understanding the value chain. Enron’s value chain included fraud, and the fraud was dependent on public displays of extravagance and success. While hidden from the outside, the relationship from the inside was obvious.

Amazon’s value chain is reflected in its leadership principles, and these are clearly laid out on its recruitment webpageso that job-seekers understand the culture from the get-go.

Ben Thompson explains the relationship between the value chain and culture on his Exponent Podcast:

“Culture is an outgrowth of the value chain. What is culture? Culture is the accumulation of decisions that worked out and it becomes subconscious.. this is how we do things.. this is how things work.

Well, by definition, if you have a value chain that is working tremendously well and throwing off huge amounts of cash, the way that value chain works and the way things have to work are going to go hand in hand. The culture is going to have the same structure, the same shape, as the value chain. The culture is the floating-in-the-air version of the value chain, but they have the exact same shape. They’re basically twins… That’s absolutely a reason why this type of analysis matters.

But the question is: how do you determine a company’s culture? If you don’t work at a company, how can you understand what that culture is and know if that’s the determining factor. And if what we’re saying is correct, you can actually start to predict a company’s culture from the outside by looking at their value chain. By understanding how they make money, how they go to market, how they acquire customers, how they acquire suppliers, all these sort of pieces and you can jump from that to say, well, this has worked so well for them, they going forward are going to be anchored in this mindset and they’re going to make assumptions.

What’s so challenging about culture issues is that you make assumptions and decisions subconsciously — you’re not even aware that you’re making them. You have Walmart, advertising a fast, faster, fastest model of ecommerce that is transparently ridiculous, but why? Because they were so locked into this killer model … when the reality is it took them years to realize that was totally wrong. Why did it take them years? Because of culture. Culture blinds them. Where did that culture come from? It came from them having a value chain that worked fabulously for decades. All of this stuff is tied together.”

— Ben Thompson

But what if you can’t determine a clear path to the market? Having multiple teams compete against one another is a great way to find your way to the future. If you have a couple of hypotheses, and you’re not really sure how to bring them to life, competing teams have natural incentives to find working solutions at scale. However, if competition is implemented poorly— which it often is—you risk hurting company culture. Also, most businesses don’t have the resources to have multiple teams solving the same problem. Most businesses have to pick a direction and then make that direction the right one.

To make a single direction work, strategy and priorities will constantly be in flux. Culture is critical in these situations. It has a significant influence on the direction that’s chosen, think of the power dynamics and native incentives for employees and teams.

It’s difficult to manage a change in direction without creating fear. People may lose the understanding of their own job function. All of a sudden, the incentives may be totally different. The company may want five KPIs instead of one. The company could drop brand marketing for search advertising, or the company could transition from managing products to building products. These are radical changes. If you have a culture of permission and give people the time to learn, experiment, and fail into this, then you have a lot of money and time, like Facebook. Most companies aren’t Facebook.

Traditional companies tend to mix test and learn with a significant amount of operational efficiency. Testing and learning is great, and necessary to find massive, step-wise discoveries. But sometimes testing and learning is a luxury. Thus, it helps to ensure that a hypothesis can be valuable even in failure. As Amazon knows, basing decisions on data will give you the greatest opportunity to be right.

The following are examples of notable corporate cultures— Netflix, Facebook, Microsoft, and Enron and the results of their culture efforts. Because every company is different, there is no single approach, and every company must conduct its own analyses and make its own path forward.

Case Studies: Netflix, Facebook, Microsoft, and Enron

“Anything is possible for a company when its culture is about listening, learning, and harnessing individual passions and talents to the company’s mission.”

—Satya Natella, Hit Refresh via Fast Company, 2017

The following case studies illustrate the fleeting and ephemeral nature of culture. Some firms have succeeded in dominating markets using diverse techniques to drive value creation through corporate culture. Others have found themselves burdened with lawsuits or annihilated.

Moreover, causal relationships between culture and corporate performance are difficult to prove. Some of these case studies provide models that have worked in the past, but they should be taken with a grain of salt; it could be one or many variables that are the reason for a firm’s success.

For example, many of these teams can attract top-tier talent from day one, which is an advantage that many other firms may lack. Therefore, employing the strategies or abandoning any of the strategies exhibited by one firm is not likely to have the same effect on another firm.

Netflix’s Dream Team

Back In 2009, Netflix published its groundbreaking Netflix “Freedom & Responsibility” culture deck, and while it was not the first company to implement such standards, it was one of the first to communicate them so transparently.

Netflix now has a whole section of its website devoted to its culture, which provides transparency and sets the tone for potential employees. Here is an excerpt from the site.

“Like all great companies, we strive to hire the best, and we value integrity, excellence, respect, and collaboration. What is special about Netflix, though, is how much we:

1. Encourage independent decision-making by employees

2. Share information openly, broadly, and deliberately

3. Are extraordinarily candid with each other

4. Keep only our highly effective people

5. Avoid rules

Our core philosophy is people over process. More specifically, we have great people working together as a dream team.”

— Netflix, 2017

Netflix’s approach to building a culture, from its recruitment strategy to its R&D, helped it transition from DVDs to a video streaming service with nearly 118 million subscribers, globally.

Kevin Kruse, founder of leadership training company LEADx.org, interviewed Patty McCord, ex-chief talent officer for Netflix and author of Powerful: Building a Culture of Freedom and Responsibility. Kruse asked McCord to explain the Netflix culture model.

According to McCord, Netflix gives employees more freedom but with responsibility. The company also communicates a clear context in which to work, “The idea of context is really, really important. Who are our competitors? Where are we at? Let me go through the P&L with you and let you understand how the financials work before we talk about the budget for your department” stated McCord.

McCord also emphasized a unique hiring approach. The hiring process is initiated by a problem that the company recognizes needs to be solved. If there are no in-house resources that can solve the problem—junior staff, for example—external candidates are selected based on their ability to solve that problem.

While Netflix has its hiring sorted out. It seems that its employees are not as impressed with its corporate culture. A study by Blind, a networking app, surveyed over 11,000 of its users in early 2020. According to Ashley Rodriguez, senior reporter for Business Insider, while just over 70% of the Netflix respondents said that Netflix “did a good job facilitating the hiring process” only 44% of Netflix respondents said the company cared about the well-being of Netflix employees, and only 32% said the company cared about employee’s professional development.

Facebook: Lessons in Scaling Culture

Facebook attracts plenty of attention from culture enthusiasts mainly because it has created a unique culture among its engineers, its most prized asset. Facebook’s engineers are given great latitude in decision making. According to Matt Rosoff, reporter for Business Insider, “Facebook is driven by engineers, not marketers or managers, and they trust each other to do the right thing.”

The following is an excerpt from Yee Lee, a four-time founder and product manager, which describes how Facebook ships code and illustrates the autonomy given to the company’s software engineers.

Development servers. Each engineer has their own copy of the entire site. Engineers can make a change, see the consequences, and reverse the change in seconds without affecting anyone else.

Code review. Engineers can propose a change, get feedback, and improve or abandon it in minutes or hours, all before affecting any people using Facebook.

Internal usage. Engineers can make a change, get feedback from thousands of employees using the change, and roll it back in an hour.

Staged rollout. We can begin deploying a change to a billion people and, if the metrics tank, take it back before problems affect most people using Facebook.

Dynamic configuration. If an engineer has planned for it in the code, we can turn off an offending feature in production in seconds. Alternatively, we can dial features up and down in tiny increments (i.e., only 0.1% percent of people see the feature) to discover and avoid non-linear effects.

Soft launches. When we roll out a feature or application with a minimum of fanfare it can be pulled back with a minimum of public attention.

Engineers are responsible for their own quality assurance testing — there’s no dedicated QA team, although a Test Engineering team does create QA tools for engineers to use.

Any engineer can check in code to any part of Facebook’s code base. Code is reviewed and can be blocked before it’s pushed live, however.

— Lee, 2011

According to Rosoff, “Facebook’s culture permits a ratio of engineers to product managers of between seven and 10 to one.” Facebook’s momentum in scaling is second to none. “This, combined with the prospect of becoming rich when Facebook goes public of course, is why so many bright people want to work at Facebook,” states Rosoff, “and that’s why older and larger companies like Google are having to pay huge bonuses to keep their staff from bolting.”

While Facebook’s culture allowed them to quickly scale to become one of the most valuable companies in the world, it isn’t without its problems. The engineer-centric “ship early and ship often” mindset that pushes out code ASAP is a major contributing factor into why Facebook struggles with consumer trust and regulation.

Since the creation of Facebook, choices were made to benefit developers both within and outside Facebook. Take this quote from Mark Zuckerberg’s 2010 F8 address when talking about the Open Graph API: “We’ve had this policy where you can’t store and cache any data for more than 24 hours, and we’re going to go ahead and we’re going to get rid of that policy,” Zuckerberg said. The audience cheered. “We think that this step is going to make building with Facebook Platform a lot simpler.”

This permanence, combined with the Open Graph API’s long list of available data from both personal and friends’ accounts, built the environment that allowed the Cambridge Analytica scandal to happen. While this issue may have been viewed with leniency for a smaller startup, Facebook had nearly 1.4 billion users and a market cap of around $200 billion when that data was available. The culture that had helped make Facebook into a giant didn’t evolve to meet the needs of a giant company.

Despite Facebook’s alleged autonomy where its engineers are concerned, the company has its mechanisms to control employees and turn them into automatons to head off incoming attacks. Facebook has “Lockdown”, Alibaba has “996, and Amazon has its already discussed rigorous culture.

The following appeared in Vanity Fair and is an excerpt from a book by a former Facebook employee Antonio García Martínez. It describes Mark Zuckerberg and Facebook’s militaristic and autocratic response to the threat posed by the launch of Google Plus in 2011.

It hit Facebook like a bomb. Zuck took it as an existential threat comparable to the Soviets’ placing nukes in Cuba in 1962. Google Plus was the great enemy’s sally into our own hemisphere, and it gripped Zuck like nothing else. He declared “Lockdown,” the first and only one during my time there. As was duly explained to the more recent employees, Lockdown was a state of war that dated to Facebook’s earliest days, when no one could leave the building while the company confronted some threat, either competitive or technical.

How, might you ask, was Lockdown officially announced? We received an email at 1:45 pm the day Google Plus launched, instructing us to gather around the Aquarium, the glass-walled cube that was Zuck’s throne room. Actually, it technically instructed us to gather around the Lockdown sign. This was a neon sign bolted to the upper reaches of the Aquarium, above the cube of glass, almost like the NO VACANCY sign on a highway motel. By the time the company had gathered itself around, that sign was illuminated, tipping us off to what was coming.

It was delivered completely impromptu from the open space next to the stretch of desks where the executive staff sat. All of Facebook’s engineers, designers, and product managers gathered around him in a rapt throng; the scene brought to mind a general addressing his troops in the field.

The contest for users, he told us, would now be direct and zero-sum. Google had launched a competing product; whatever was gained by one side would be lost by the other. It was up to all of us to up our game while the world conducted live tests of Facebook versus Google’s version of Facebook and decided which it liked more. He hinted vaguely at product changes we would consider in light of this new competitor. The real point, however, was to have everyone aspire to a higher bar of reliability, user experience, and site performance.

In a company whose overarching mantras were DONE IS BETTER THAN PERFECT and PERFECT IS THE ENEMY OF THE GOOD, this represented a course correction, a shift to the concern for quality that typically lost out to the drive to ship. It was the sort of nagging paternal reminder to keep your room clean that Zuck occasionally dished out after Facebook had suffered some embarrassing bug or outage.

Rounding off another beaded string of platitudes, he changed gears and erupted with a burst of rhetoric referencing one of the ancient classics he had studied at Harvard and before. “You know, one of my favorite Roman orators ended every speech with the phrase Carthago delenda est. ‘Carthage must be destroyed.’ For some reason I think of that now.” He paused as a wave of laughter tore through the crowd.

The aforementioned orator was Cato the Elder, a noted Roman senator and inveigher against the Carthaginians, who clamored for the destruction of Rome’s great challenger in what became the Third Punic War. Reputedly, he ended every speech with that phrase, no matter the topic.

Carthago delenda est. Carthage must be destroyed!

Zuckerberg’s tone went from paternal lecture to martial exhortation, the drama mounting with every mention of the threat Google represented. The speech ended to a roar of cheering and applause. Everyone walked out of there ready to invade Poland if need be. It was a rousing performance. Carthage must be destroyed!

In the Trenches

The Facebook Analog Research Laboratory jumped into action and produced a poster with CARTHAGO DELENDA EST splashed in imperative bold type beneath a stylized Roman centurion’s helmet. This improvised printshop made all manner of posters and ephemera, often distributed semi-furtively at nights and on weekends, in a fashion reminiscent of Soviet samizdat. The art itself was always exceptional, evoking both the mechanical typography of World War II-era propaganda posters and contemporary Internet design, complete with faux vintage logos. This was Facebook’s ministry of propaganda, and it was originally started with no official permission or budget, in an unused warehouse space. In many ways, it was the finest exemplar of Facebook values: irreverent yet bracing in its martial qualities.

The Carthago posters went up immediately all over the campus and were stolen almost as fast. It was announced that the cafés would be open over the weekends, and a proposal was seriously floated to have the shuttles from Palo Alto and San Francisco run on the weekends, too. This would make Facebook a fully seven-days-a-week company; by whatever means, employees were expected to be in and on duty. In what was perceived as a kindly concession to the few employees with families, it was also announced that families were welcome to visit on weekends and eat in the cafés, allowing the children to at least see Daddy (and, yes, it was mostly Daddy) on weekend afternoons. My girlfriend and our one-year-old daughter, Zoë, came by, and we weren’t the only family there, by any stretch. Common was the scene of the swamped Facebook employee with logo’d hoodie spending an hour of quality time with his wife and two kids before going back to his desk.

And what was everyone working on?

For those in the user-facing side of Facebook, it meant thinking twice on a code change amid the constant, hell-for-leather dash to ship some new product bell or whistle, so we wouldn’t look like the half-assed, thrown-together, social-media Frankenstein we occasionally were.

For us in the Ads team, it was mostly corporate solidarity that made us join the weekend-working mob. At Facebook, even then and certainly later, you got along by going along, and everyone sacrificing his or her entire life for the cause was as much about self-sacrifice and team building as it was an actual measure of your productivity. This was a user battle, not a revenue one, and there was little we could do to help wage the Google Plus Punic War, other than not totally horrifying users with some aggressive new Ads product—something nobody had the nerve to do in those pre-IPO days.

— García Martínez, Antonio. 2016. Chaos monkeys: obscene fortune and random failure in Silicon Valley.

Enron: Values vs. Culture

“Units were sometimes reorganized three or four times a year, which always meant moving people around, at a cost of roughly $500 a person just to set up a new desk…On any given weekend, several hundred people would be moved from one floor to another at Enron.”

— Cheryl Brashier, administrative assistant, Enron

Enron is infamous for a culture that resulted in explosive public demise. While the inside of the company was shrouded in darkness and turmoil, Enron was pushing value statements that made it seem like a responsible and positive corporate citizen. This mismatch is covered in-depth in Patrick M. Lencioni’s Harvard Business Review article, “Make Your Values Mean Something.” An excerpt from the article:

“Take a look at this list of corporate values: Communication. Respect. Integrity. Excellence. They sound pretty good, don’t they? Strong, concise, meaningful. Maybe they even resemble your own company’s values, the ones you spent so much time writing, debating, and revising. If so, you should be nervous. These are the corporate values of Enron, as stated in the company’s 2000 annual report. And as events have shown, they’re not meaningful; they’re meaningless.”

— Patrick M. Lencioni, Harvard Business Review

Enron is a shining example that written values and mission statements, while an important part of creating a corporate identity, are meaningless without culture creation and management.

Enron’s culture was well known for its lavish excesses that persisted right up until the firm’s bankruptcy. Neela Banerjee, David Barboza, and Audrey Warren reported in-depth on Enron’s unchecked lavish spending—a $1.5 million-dollar Christmas party at Enron Field and Waterford crystal gifts for secretaries day, for example—which created a culture that ultimately led to the company’s downfall.

The internal “go-go” culture, according to Banerjee, Barboza, and Warren, was buttressed by lax or nonexistent risk controls that had once been state of the art. Enron staff were rewarded with inflated salaries, which they justified by 12-hour work days and extended travel schedules. Enron employees flew first or business class and stayed at luxury hotels. According to Banerjee et al., “The company’s parking garage was filled with Porsches, Ferraris, and BMW’s, emblems of the sizable bonuses many employees earned.”

”Appearances were very important,” said Jeff Gray, a former economist at Enron Energy Services.” It was important for employees to believe the hype just as it was important for analysts and investors to believe it.”

Enron is an example of an unsustainable culture, albeit one that employees initially fell in love with. It was dizzyingly intoxicating in the short term, but there was no solid foundation on which it could survive—it was all a ruse.

According to one employee, ”We knew we weren’t making money, but the extravagance was what made it great to work there.”

Microsoft: A Culture Turned Full Circle

Microsoft has come full circle where its culture is concerned. While it was once the most powerful company in the world, its antitrust case and its debacle with stack ranking hobbled the company and created a culture of surveillance and fear.

In the early 2000s, Microsoft’s journey passed through what Kurt Eichenwald, writer for Vanity Fair, called, “The Lost Decade.” During this period, Microsoft struggled with bleak sales from Windows Phone 7 and glitches with various technologies while Google, Facebook, and Apple came to the fore with a mix of social media platform and tech products. Microsoft relied on Windows, Office, and servers to prop up its financial performance.

According to Eichenwald, in the 2000s, Microsoft’s stock barely budged from around $30, while Apple’s stock grew more than 20 times over the same period.

“In December 2000, Microsoft had a market capitalization of $510 billion, making it the world’s most valuable company. As of June [2012] it is No. 3, with a market cap of $249 billion. In December 2000, Apple had a market cap of $4.8 billion and didn’t even make the list. As of this June, it [Apple] is No. 1 in the world, with a market cap of $541 billion,” wrote Eichenwald in 2012.

What caused Microsoft’s role reversal during its lost decade? Eichenwald describes Microsoft’s change as one that went from a lean machine led by young, talented visionaries to a bloated bureaucracy that stifled creative ideas, if any even emerged.

“Where Microsoft programmers were once barefoot programmers in Hawaiian shirts working through nights and weekends toward a common goal of excellence; instead, life behind the thick corporate walls had become staid and brutish. Fiefdoms had taken root, and a mastery of internal politics emerged as key to career success,”

— Kurt Eichenwald, Vanity Fair

Rather than crippling competitors, co-workers were experiencing internal conflict. Policies like stack ranking meant that employees were rewarded for sabotaging their teammates. When the antitrust case occurred, Microsoft executives buckled under the pressure of constant scrutiny.

Even Bill Gates, when he signed a consent decree to resolve one of its monopoly investigations in 1994, was aware of how entrenched the culture was at Microsoft. He told a reporter that the decree was essentially pointless for the company’s various divisions: “None of the people who run those divisions are going to change what they do or think,” Gates said.

In 2014, Satya Nadella took over as CEO from Steve Ballmer. Lo and behold, Nadella changed the culture at Microsoft to one that is customer focused. According to Peter Cohen, contributor to Forbes, “Nadella created a culture that focused Microsoft on supplying customers what they wanted rather than forcing Windows products down their gullets.” As a result, Microsoft stock soared from $90 to around $180 in mid-2020. Fast Company ranked Microsoft as the second most innovative company in 2020 beating out Tesla and with Snap as number one. Nadella’s approach changed the culture and the bottom line.

According to Cohen, Nadella coalesced its global subsidiaries around the customer’s wants and needs. Improved attention to customers garnered consumer trust and a willingness to buy Microsoft’s products once again.

Additionally, Microsoft had the resources that allowed it to scale new products. The company changed its development processes, and its people. In the words of Nadella,

“We had to introduce and to promote new products and business models ([software as a service] vs. perpetual [licenses]). We had to drive our employees to interact with new corporate decision-makers—business vs. the original technical ones. We had to scale our employees to master new advanced products. In order to be successful, new skills were needed. We had to promote and to support learning.”

— Satya Nadella

This was what Nadella called the “growth mindset.”

Nadella encouraged his teams by allowing them to learn, try, and fail, and relied heavily on data at all times. However, he also loaded the pressure onto the shoulders of his 150 top executives,

“Once you become a vice president, a partner in this endeavor, the whining is over. You can’t say the coffee around here is bad, or there aren’t enough good people, or I didn’t get the bonus. To be a leader in this company, your job is to find the rose petals in a pile of shit. You are the champions of overcoming constraints.”

— Satya Nadella

The Downsides of Performance-Based Culture: How Stack Ranking Backfired for Amazon, Microsoft, and Yahoo

While the performance-based cultures built by companies like Amazon have been lauded, they don’t exist without their downsides. Measuring and incentivizing employee performance can be a great way to achieve results. However, go too far and the culture can quickly become one of fear.

From the Harvard Business Review article, “Making Business Personal” by Robert Kegan, Lisa Lahey, Andy Fleming, and Matthew Miller, fear is an inhibitor to evolution, “To an extent that we ourselves are only beginning to appreciate, most people at work, even in high-performing organizations, divert considerable energy every day to a second job that no one has hired them to do: preserving their reputations, putting their best selves forward, and hiding their inadequacies from others and themselves. We believe this is the single biggest cause of wasted resources in nearly every company today.”

We find an example of policies that can create cultures of fear with the once-trendy practice of stack ranking.

Stack ranking is an employee rating system that some have described as a Darwinian practice that amounts to survival of the fittest. It is a process that has been implemented (and subsequently dismantled) at tech giants including Amazon, Microsoft, and Yahoo. Jack Welch, CEO of GE, first implemented the process that was designed to eliminate less productive staff and constantly build up a team of the most productive workers. Basically, employees rated their peers.

A former software developer at Microsoft described the stack ranking experience to Eichenwald, writer for Vanity Fair, “Every unit was forced to declare a certain percentage of employees as top performers, then good performers, then average, then below average, then poor,” said the software developer, “If you were on a team of 10 people, you walked in the first day knowing that, no matter how good everyone was, two people were going to get a great review, seven were going to get mediocre reviews, and one was going to get a terrible review.”

According to Julie Bort, chief tech correspondent for Business Insider, “the problem is that it’s really only valuable for a short time, such as when a company is reorganizing, stack ranking experts say. Using it long-term tends to create a dog-eat-dog kind of culture.”

Amazon used stack ranking, or “rank and yank” as it was coined by those in the know, to rate employees against each other as opposed to how well they met their job requirements. Amazon was not the only tech giant to try stack ranking. According to Bort, Microsoft tried it but ditched it in 2015, and Yahoo CEO Marissa Mayer attempted to use it when attempting to fix the company’s woes in 2012.

Eichenwald provides an in-depth account of Microsoft’s rise and fall including its dabbling in the stack ranking process. According to some that Eichenwald talked to, it was considered “the most destructive process inside of Microsoft, something that drove out untold numbers of employees.”

The result for Microsoft was a culture where the pressure employees felt to be strong competitors internally overshadowed the focus on team dynamics and contributed to the company’s prolonged lackluster performance.

Changing Existing Culture

“A recent Deloitte survey showed that 94% of executives believed that a strong culture was important to business success. But if you asked them who was responsible for managing culture or how they would manage it, most wouldn’t have a clue.”

— Charles O’Reilly via Lisa Holton, Stanford, 2014

Changing culture is a long and difficult journey. O’Reilly notes that most mature companies don’t take risks. They are focused on incremental short-term improvements, and employees are rewarded for behaviors that are not conducive to long-term success. They follow proven methods rather than experimenting with new ones.

O’Reilly goes on to state that part of the difficulty in changing a culture is making people understand and elucidate what it is so that they can then envision how to change it. Leadership faces the challenge of seeing the data that makes up their reality and helping their organization understand. As Ben Thompson of Stratechery explains:

“This is the power CEOs have. They cannot do all the work, and they cannot impact industry trends beyond their control. But they can choose whether or not to accept reality, and in so doing, impact the worldview of all those they lead.”

But to drive change is more than understanding the need to change. Culture change must go far beyond inviting thought leaders to speak at annual events. That helps to educate managers and employers of the need for a positive environment, but it won’t lead to concrete change.

For that, you need metrics. Efforts and results need to be quantified so that change is transparent and there are actual results. Through measurements and rewards, there is accountability. Another point to remember is that a culture assessment might reveal that not all areas of an organization might require change—there may be pockets of an organization that require change while other core cultural components may be strong.

Identifying Necessary Cultural Change

“Any organization focused on transformational change must commit to a focused initiative designed to help turn the survey analysis into action. The most basic part of this effort is a feedback and action planning process to take place throughout the company”

— Daniel R. Denison, founding partner, Denison

Sometimes, the effects of a misaligned culture can be felt and observed throughout a workplace. People talk behind other people’s backs, desks are devoid of personal belongings, or passive-aggressive emotions are felt throughout the building. While these signals are all important, they won’t convince leadership that a problem exists. Data is required.

Because change requires funding, and funding requires metrics, the root cause of cultural issues need to be quantified to secure buy-in from leaders. Before beginning to think about culture change, the existing culture needs to be assessed to extract meaningful metrics.

Consider the following questions that reflect an organization’s culture:

- Who makes decisions?

- How are decisions made?

- Who has direct communication with who?

- How are departments structured?

- How are employees incentivized?

- How are internal conflicts resolved?

- How is recruitment and retention managed?

In the best-case scenario, there is supporting data that answers these questions. For example, determining how much revenue comes from one area can indicate the cultural health of separate business functions. Areas with strong revenue might offer ideas for best practices that other parts of the organization can emulate. Similarly, determining how long revenues have been generated in one area may signal that decisions are too focused and there is a risk of disruption from lack of diversity.

With data and metrics, culture becomes more tangible, and there is a basis for a plan to rebuild or improve any frailties.

But transition is hard. If you put someone into an unfamiliar environment, there will be a learning curve. Some within the company will have trouble during a transition. People must go from being “pioneers” to “settlers,” and pioneers often have a hard time settling down. It helps to create temporary roles in the organization to shepherd the company across the chasm. While the target market segment manager works to break onto the beachhead, the whole product manager handles product debugging.

Culture Assessment Tools

There are increasing tools available for cultural assessments. For examples of software for culture surveys, see Denison’s organizational culture surveys, Creative Difference, and Know Your Company. Gary Swart, general partner at Polaris Partners gives examples of questions that can be asked in a survey to gauge the state of culture.

Typical data that reveal cultural factors are worker to manager ratios and retention rates. However, some companies experience high turnover but still manage to excel. PayScale lists the companies with the most and least “loyal” employees according to average employee tenure. High on the list of companies with the least loyal employees are Amazon, Google, Mass Mutual Financial Group, and Aflac.

What Does a Growth-oriented Culture Look Like?

Charles A. O’Reilly is the Frank E. Buck Professor of Management at Stanford Graduate School of Business. In research conducted with Jennifer A. Chatman and Bernadette Doerr at the University of California–Berkeley and David F. Caldwell at Santa Clara University, he pointed to grit, adaptability, and resilience in employees as cultural factors that drive growth in tech firms specifically.

The team used the adaptive nature of Silicon Valley firms as illustrative examples of adaptable cultures and contrasts these firms with Ford’s rigidity before CEO Alan Mulally took the helm.

To define adaptability, the researchers cite cultures that nurture the following behaviors:

- risk-taking

- a willingness to experiment

- innovation

- personal initiative

- fast decision-making and execution

- the ability to spot unique opportunities

O’Reilly and colleagues also noted that adaptive cultures put less emphasis on “being careful, predictable, avoiding conflict, and making your numbers.” According to O’Reilly, “Ford attempted three turnaround efforts over the last 15 years. Two of them failed abysmally. This last one, under Mulally, succeeded but only because Mulally succeeded in turning around a dysfunctional culture.”

The researchers conclude that “corporate cultures that emphasize adaptability generally produce “revenue growth, market and book value, ‘most admired’ ratings, employee satisfaction, and stock analysts’ recommendations.” The essential mechanism, O’Reilly says, “is the alignment of culture with strategy.”

Building Culture:

Case Studies on CSAA Insurance Group and Thompson Reuters

CSAA Insurance Group (CSAA IG)

CSAA Insurance Group (CSAA IG) has almost 4,000 employees and is an interesting model and study on culture change. Soren Kaplan, author of The Invisible Advantage and founder of InnovationPoint describes CSAA’s approach in the Harvard Business Review.

The company first addressed its capabilities in terms of skills, and “innovation” was added to the company’s values statement and included as a core competency for employees. However, if employees were to be evaluated based on innovation, the term would have to be clearly defined.

The executive team chose to specify three types of innovation that employees should strive to embody—incremental, evolutionary, and disruptive. Clearly, evolutionary and disruptive innovation are tall orders, so most innovation was “small tweaks that advanced the core business,” for example, improvements to existing processes, customer experience, and insurance products.

Not surprisingly, the company allocates fewer resources to evolutionary and disruptive innovation and invests more in employee training, innovation tools, and design-thinking based initiatives. According to Kaplan, “Employees participate in a half-day program that tackles real business problems facing their workgroups and results in a prioritized list of ideas.”

The efforts have paid off in terms of tangible and measurable results. For example, “a team of insurance underwriters analyzed call data and led improvements to voice prompts that reduced misrouted phone interactions to their department by 40%. Other teams have helped streamline the process for issuing proof of insurance cards and are contributing to prototyping efforts for ‘smart claims’ systems, allowing customers to submit images of damaged property for online assessment.”

To make sure that action is taken on ideas solicited by employees, managers, whose act similarly to culture carriers, discuss the various ideas with teams and select specific ideas to be cleared by upper management. “Employees also have access to CSAA IG’s “Innovation Hub,” an online portal with a design-thinking toolkit, a calendar of innovation-related events, self-paced training materials, and articles from innovation experts. The company has also set up an idea management platform, where various departments can post their innovation challenges, and where the crowd can contribute, evaluate, and develop solutions.

To help generate excitement for the idea management platform, during the first online innovation challenge event, anyone who submitted an idea was surprised with a physical paper light bulb posted in their cubicle workspace. With light bulbs popping up all around the office, employees’ motivation to participate skyrocketed—and the company’s first online challenge received an 80% participation rate.”

Thomson Reuters

Ron Ashkenas, Partner Emeritus at Schaffer Consulting and author of The Boundaryless Organization, The GE Work-Out, and Simply Effective, and Cary Burch, SVP of Innovation for Thomson Reuters, comment the innovation efforts of Thomson Reuters in the Harvard Business Review.

Thomson Reuters is a $12.5 billion global information solutions company facing all the challenges of a scaled company struggling to maintain an evolutionary culture.

Acquisition was the main mode for growth until the senior leadership established a “catalyst fund” in 2014. The fund supported internal innovation teams conducting rapid proof of concept on new ideas.

“The fund was announced on the company’s internal website, and teams from anywhere in the businesses were invited to submit their suggestions. To access the fund, teams had to complete a simple two-page application about their idea, the potential market, and the value to the customer (what problem was being solved). The teams with the most compelling ideas were given an opportunity to present and defend their idea to the innovation investment committee, which included the CEO, CFO, and a few other senior executives. In the first month, five ‘winners’ were announced and then immediately publicized on the Thomson Reuters internal web site. This triggered a great deal of interest, and a steady flow of applications.”

— Ron Ashkenas & Cary Burch, Harvard Business Review, 2014

The company also hired a full-time innovation leader and developed innovation metrics (such as number of ideas being considered and the amount of revenue from new products/services). These data allowed the innovation leader to report the timelines of initiatives and their potential value, information necessary to obtain the buy-in of the executives.

In the same vein as culture carriers, the company appointed “innovation champions” in every business, who “created a common terminology for innovation across the company so that everyone referred to the same types of innovation (e.g., product vs. operational) and referenced the same stages (e.g., “ideation” and “rapid prototyping”). The company built an online Thomson Reuters innovation “toolkit” for employees, and an innovation network intranet where entrepreneurs could share concepts and connect with others to solve customer problems in new ways. The company initiated a communications campaign with blogs, articles, and video interviews with internal innovators and organized an “enterprise innovation workshop,” to identify 10 innovations that would leverage existing company assets and implement them in 100 days or less.