Mergers and Acquisitions

You will learn about mergers and acquisitions (M&A), one of the most powerful and risky tools in the innovators toolbox.

In this training, you will

- Learn what mergers and acquisitions (M&A) is.

- Understand how to find “synergy” between organizations.

- Learn the risks associated with mergers and acquisitions.

- Explore when to buy instead of build.

- Learn about the deal lifecycle.

- Learn about divestiture.

- Review a case study on Cisco.

- Read insights from M&A strategy leaders.

Skills that will be explored

M&a Overview

Among the tools firms can use to grow, mergers and acquisitions (M&A) are perhaps the most daunting. These massive deals are rife with legal and bureaucratic hurdles, but they have created some of the most powerful and recognizable firms in history.

Many companies pursue M&A to grow and transform their businesses. The COVID-19 epidemic has drastically hindered M&As in 2020, but 56 percent of more than 2,900 executives surveyed globally by consultancy EY were planning an acquisition in the next 12 months stating that they were focused on long-term growth despite the current crisis. In fact, the report states that M&A activity may show up an uptick, “If there is any prolonged downturn due to the current crisis, executives may be bolder in their ambitions and look to acquire those assets that will help them accelerate into an upturn faster,” the report said.

M&As in 2020 and beyond are unlike those of past decades. The motives behind these deals have evolved as companies have transitioned to an economy centered around new technologies and the internet.

Evolving M&A Motives

“M&A goals are changing. Without question, many companies still use deals to achieve economies of scale and improve efficiency. But increasingly, they’re also trying to achieve transformation.”

— PWC, 2017.

The current COVID-19 epidemic has caused executives to change tacts. Ten years ago, M&As where a way to achieve economies of scale while three years ago, technology and innovation were the drivers for M&As. In 2020, however, securing supply chains are front and center of today’s M&A activity. According to a recent report by EY, “Facing this challenge [COVID-19], executives are now changing their operating models. An unparalleled shutdown of activity in many parts of the world has precipitated new actions, with more than half (52%) of respondents actively taking steps now to change their current supply chain and more than a third (36%) accelerating investment in automation. And the vast majority of those not immediately acting are currently re-evaluating their options.”

Still, EY also found that close to 70% of executives plan to return to a focus on digital and technology (71%) investments once the pandemic is managed. Thus, executives are looking beyond the current crisis and downturn and plan to move nimbly to reinvent their businesses to “help fuel the recovery and create long-term value for all their stakeholders.”

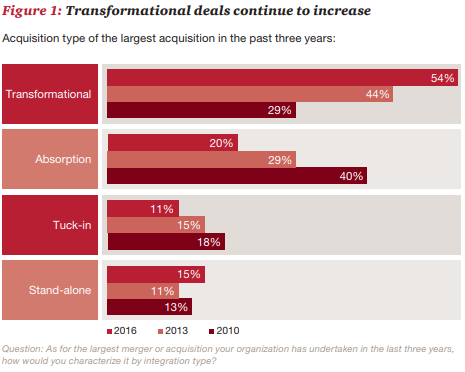

Research from PwC predating the COVID-10 pandemic found that over 50 percent of respondents to a Fortune 1000 survey said that the largest transactions they had completed in the last three years were transformational.

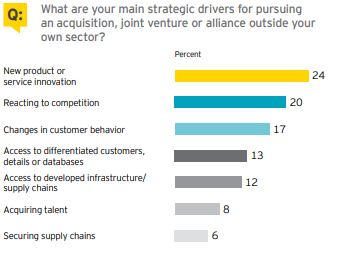

Further exploring these shifting motivations, the graph below from EY shows the reasons why companies pursued acquisitions in 2017. The most popular reason given by respondents was to develop new products followed by reacting to competitors. The emphasis was on technology advancement rather than factors such as securing better supply chains, organizational efficiency through hiring, or customer management.

—Source: EY, 2017

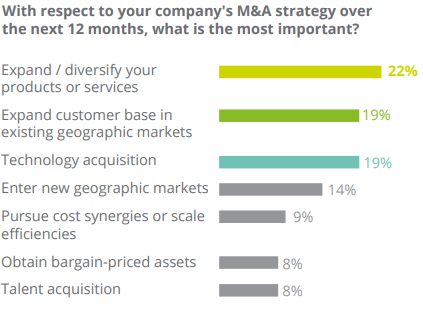

A Deloitte survey echoes this sentiment. The survey, found in “M&A Trends – Year-end report 2016,” showed that the main goals that companies try to achieve through mergers are related to expansion in products, markets, and technology acquisitions. For example, Walmart is experimenting with alternate e-commerce platforms and acquired Jet, a move that was a huge component in the retailer’s digital transformation. Or consider Target’s acquisition of Shipt to shift to grocery delivery services and follow a new digital direction.

—Source: Deloitte, 2016

In times of economic normalcy, and once the COVID-19 pandemic is behind us, technology giants will continue to absorb companies to react to digital change. It’s with these motivations in mind that we investigate M&As and how they can drive value amidst digital change.

Defining the M&a Spectrum

There are a few ways to classify deals depending on their intent and structure. The two main classifications of deals are based on functional roles: vertical mergers and horizontal mergers. (A third type, conglomerate mergers, won’t be covered because there is a weaker relationship between these tools and innovation.)

Horizontal Mergers

A horizontal merger, according to Investopedia, “occurs between firms that operate in the same space, as competition tends to be higher and the synergies and potential gains in market share are much greater for merging firms in such an industry.”

Historically, when a company pursued a horizontal M&A and acquired another entity in the same industry or sector space, the purpose was typically to subsume a direct competitor, increase market share, and achieve economies of scale by decreasing average cost. Some of the most visible horizontal deals in recent history have been large companies acquiring startups that have built significant and fast-growing user bases.

It would be impossible to talk about this without mentioning Facebook’s $1 billion acquisition of Instagram. At the time, people were confused by this deal. Why did Facebook pay $1 billion for an app with no revenue and 13 employees? Since the acquisition, the answer has become clear. Instagram has grown from 30 monthly active users to over 800 million. It’s no surprise that the deal has been lauded as one of the greatest acquisitions of the 21st century.

While some analysts were focused on the startup’s non-existent revenue, Facebook saw a product that was taking hold of the younger demographic. It was built for mobile phones, which were experiencing rapid technological advancement at the time. Facebook also understood the opportunities made possible by integrating the two products. Without this integration and symbiotic relationship, it’s doubtful that Instagram would have been able to reach such scale.

Vertical Mergers (Vertical Integration)

“Today, most organizations pursue vertical integration from control, risk, and flexibility standpoints. Control of resources, limiting or taking risks, and flexibly changing direction quickly without the burden of commitments.”

—Erik Kayser, partner and management consultant, Implement Consulting Group.

Vertical deals are an effective way to transform businesses and improve the efficiency of a firm’s value chain. Vertical mergers give firms better control of shipping and logistics, for example, through gig economy shipping, digital platforms, or the acquisition of suppliers.

Target’s acquisition of Shipt was an excellent example. The retailer paid $550 million to acquire the gig economy delivery service and access to same-day fulfillment capabilities in addition to Target’s existing operations. This illustrates a broader trend within retail: integrating the entire vertical. Pressured by Amazon, retailers are using acquisitions to quickly gain access to the whole value chain including supply, fulfillment, e-commerce, physical stores, and more.

Controlling the supply chain can mean controlling the market. Acquiring a vendor or supplier can improve operational efficiency and increase profits by controlling costs and product availability. Starbucks, for example, has vertically integrated from the bean to the cup. The company owns the whole supply chain from the coffee bean farms to the roasting plants, the warehouses, the distribution centers, and the retail outlets.

Further Reading:

- When and when not to vertically integrate – McKinsey

- This article by John Stuckey, director for McKinsey, and David White, principal for McKinsey, is an essential read for anyone thinking about pursuing vertical integration. It is dated 1993 but provides a robust examination of the core components of these deals.

The Search for Synergy

“We look for many singles and doubles on revenue synergy, instead of one home run.”

– VP of Strategy, Deloitte, 2017.

Companies pursue both vertical and horizontal deals in an attempt to gain synergies, and two types of synergies generally arise from M&As: 1) revenue synergies, when a combined company generates more sales than the two companies could separately, and 2) cost synergies, when the combined company can reduce average costs to a greater extent than the separate companies (economies of scale).

In a Deloitte survey of 528 executives involved in mergers, almost 60 percent of the deal synergies sought were anticipated to come from revenue rather than cost sources. But anticipating synergies is much different than experiencing them. According to McKinsey research, “The greatest errors in estimation appear on the revenue side—which is particularly unfortunate since revenue synergies form the basis of the strategic rationales for entire classes of deals, such as those pursued to gain access to a target’s customers, channels, and geographies. Almost 70 percent of the mergers in our database failed to achieve the synergies expected in this area.”

How can firms increase their chances of experiencing synergies?

In its report, “Revenue Synergies in Acquisitions In Search of the Holy Grail,” Deloitte explains how to achieve revenue synergies. According to the report, combining short-term, quick wins with longer-term creativity could achieve revenue-synergy success. For example, pursuing shared distribution channels can increase synergy and boost revenues in the short term, and pursuing multiple channels can sustain those revenue synergies for longer.

From the beginning, as soon as a deal is announced, Deloitte assigns a project management officer with a relentless focus on synergies and incorporates targets into the operational plan to incentivize teams. The operation plan, according to Deloitte, looks a bit like this.

- Pursue the low-hanging fruit

- Align around cross-selling and channels

- Enforce efficient decision making on goals, being mindful of operating model implications

- Cast a wide net

- Pursue multiple types of synergy initiatives to increase chances of success

- Lead change management activities across both organizations

- Enlist partners, clients, and other key stakeholders in guiding and informing key decisions

- Lead with innovation

- Invest in growth opportunities with long-term potential

- Balance near-term and long-term synergy initiatives

- Lay the foundation for go-to-market transformation

- Dig into the data details

- Use quality data to drive analytics-driven insights

- Establish and empower a dedicated integration team

- Budget for success and incentivize teams

- Plan the work; work the plan

- Plan for pre-close synergy and clean room (or data room) activities

- Activate integration teams with commercial analytics capabilities

- Remain focused on targets

—Source: Deloitte, 2017

According to Deloitte, initiatives such as cross-selling, early planning, and establishing integration teams are integral to realizing revenue synergies from a merger. But what about the risks?

M&a: the Risks and Hurdles

According to KPMG BOXWOOD, after a merger, “everything is uncertain – office locations, job titles and roles, reward systems, organizational structures, culture and values, the people you work with – they’re all up for discussion.” Announcing key decisions early in the merger discussion process can mitigate the uncertainty among employees and its knock-on effects on revenues.

Another hurdle for the leadership team, according to KPMG BOXWOOD, is to define the new goals of the organization and obtain stakeholder buy-in so that the two entities collaborate from the outset. Preferably, the new goals should not require major changes in thinking from either the collective post-merger organization or the individuals within.

Getting people to let go of old models and ways of thinking is difficult. In the case of Dixons and Carphone Warehouse, KPMG BOXWOOD states that culture surveys and change ready assessments were used to prepare staff for the next steps in the merger and to help them understand and come to terms with change. Staff were shown how the new merged stores would work so that they could envision their roles and anticipate how to manage post-merger day-to-day practicalities. The reason for a merger, and the benefits that it will bring, need to be compelling enough to justify the disruption to affected staff.

Before any merger is contemplated, KPMG BOXWOOD suggests that companies should identify key indicators as benchmarks where improvements are expected. As the merger progresses, these metrics can be used to sustain efforts to make the merger successful. Positive results will build trust in the new leadership and boost morale and productivity. Metrics will also show where changes need to be made, increasing the chance that the merger will be successful.

Use Metrics for a Realistic Picture of Deals

Steve Carnes, an M&A specialist, suggests that companies clearly define goals before deciding what metrics to use to measure merger outcomes. According to Carnes, an organization must decide whether it is focusing on measuring sales or products, building a footprint in a target market, or eliminating a competitor.

Carnes recommends a Sales-Iinventory-Operations-Planning (SIOP) process: “Within a company, people are selling things, making things, and keeping track of how it’s all going. Consider each step, think about your goals, and ask yourself ‘where are the gaps, and how are you going to improve them?’”

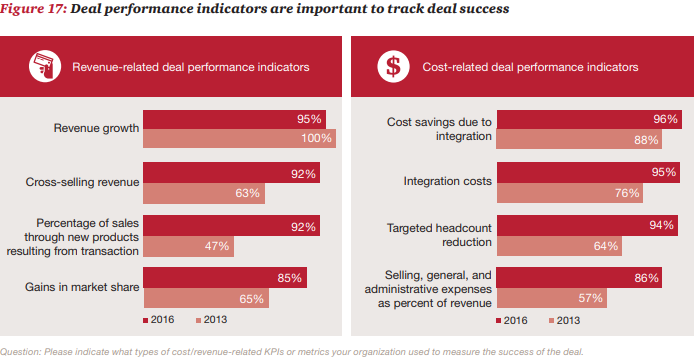

Below are some deal performance indicators suggested by PwC.

—Source: PwC, 2017

Metrics for Integration

Establishing metrics and key indicators to assess the value of entering into a deal will help mitigate risk and facilitate communication with shareholders.

PwC experts Vinay Couto, John Plansky, and Deniz Caglar are the authors of “Fit-for-Growth.” They outline a discipline for companies working through the different stages of preparation for a transformative deal. The discipline calls for alignment of cost structures and capabilities; it also calls for the design of an operating model that enables and sustains cost reductions and then creates the right conditions for managers to drive growth.

For early-stage M&A, Carnes recommends determining whether the target firm’s performance is better than the market average. If not, why do the deal? Carnes suggests looking at year-over-year growth rates for the last three years along with projections for the next three. Market context matters: explosive growth in a hot market might not be impressive.

Carnes also suggests benchmarking employee sales versus the cost ratio with the industry average to determine a company’s performance and potential. Typically, Carnes finds that a lower-than-average ratio indicates problems that might range from brand and market positioning to sales process efficiency or overstaffed departments and a lower level of automation. Carnes advocates looking at the cost of sales per employee and as a percentage of revenue.

Service-Level Agreements (SLAs) are another useful metric. Important items are the targets set for order fulfillment and lead time: does the company meet them, and are these targets essential? Does the value added justify the cost, or are the SLAs not, in fact, a true competitive advantage?

Leading companies are using deals to expand their product lines and to be more competitive in new product development.

When to Buy Instead of Build: Tech Acquisitions and Acquihires

“I have never cared what something costs; I care what it’s worth.”

—Ari Emanuel, Talent Agent and co-CEO of William Morris Endeavor

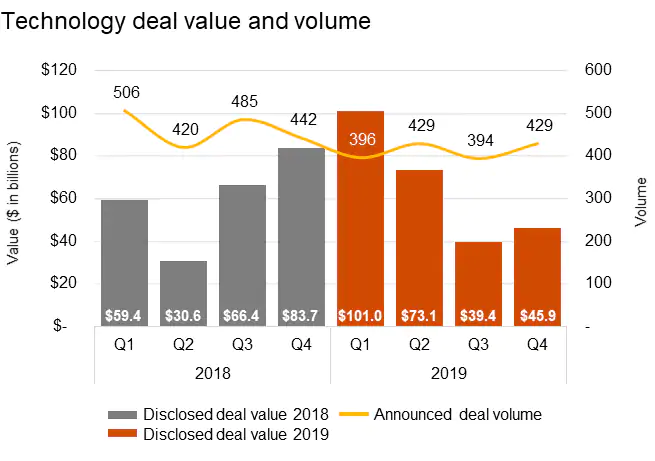

The technology deals market is dynamic, and technology acquisitions are attracting the most attention these days. During the first quarter of 2019, 429 technology deals were announced for a total disclosed deal value of $45.9 billion.

—Image Source: PWC, 2019

Since 2018, software has been the most active sector, particularly acquisitions of SaaS and data analytics firms. According to the report by PwC, “AI was a driving force behind several deals, with two of the top four transactions in the semiconductor space being AI-related (Nvidia’s $6.8 billion acquisition of Mellanox and Intel’s $2 billion acquisition of Habana Labs). On the software side, AI companies were popular targets as companies were looking to enter new markets (VMWare’s acquisition of Carbon Black), expand capabilities (Salesforce’s acquisition of ClickSoftware), and innovate new technologies (Facebook’s acquisition of CTRL-labs).” Semi-conductors were the next most active sub-sector, encouraged by the soft chip market and the trade war with China.

Buying vs. Building

It makes sense that rather than develop a technology from scratch, a company should acquire or merge with another company that already controls that technology. These types of mergers can save years of development time.

The emphasis on technological capabilities over recent years, and the need to acquire such capabilities to be competitive, means that non-digital companies have shown more interest in digital deals (defined as the acquisitions of digital products and services, new digital business models, and the digitization of the value chain).

According to a white paper by Deloitte, digital deals are becoming a fast route to new product markets and technology advancement for many industries. Such deals provide quick and complete access to otherwise unattainable technology in IoT, fintech, cleantech, healthtech, big data and cognitive analytics, robotics, wearables, AI, etc. In fact, according to research from Joerg Krings, advisor to PwC’s strategy consulting group, and J. Neely and Olaf Acker, leading Strategy& and PwC practitioners, companies in non-digital industries completed 48 percent more digital deals in 2015 than they did in 2011.

Image Source: PwC

The Challenges of Technology Deals

Technology deals are vastly different from traditional deals. Rob Fisher, Greg Nahass, and J. Neely, partners with Strategy& and PwC, reference “technology megadeals,” of which Facebook’s $22 million acquisition of the five-year-old startup What’s App in 2014 is a good example. These megadeals often feature “huge valuations, narrow focus, tiny revenues, and entrepreneurial management that may force an acquirer to toss out its playbook.” The tech sector is characterized in many cases by small companies with high valuations, and the decision to acquire, therefore, is a difficult one.

According to a Deloitte white paper, because competition may come from an unexpected source, acquiring firms should identify startups or companies with new or different business models and either acquire them or surpass them. Companies need a way to gauge the value creation potential of a deal, and firms need to know how best to integrate a new tech startup so that value is not lost. Companies now require a completely new skill in the context of mergers: the ability to identify the most promising digital targets from a shortlist that might number in the hundreds.

“Some technology acquisitions that looked good on paper have failed because the purchaser did not really understand what it was buying or its in-house staff did not know the right questions to ask when conducting due diligence.”

—Deloitte, 2011

Although the focus is often on the technology being acquired in a tech deal, a buyer of a startup must consider the revenue synergies to find a competitive valuation. Facebook paid $1 billion for Instagram in 2012, which had no revenue at the time. Did the revenue synergies really amount to that type of valuation?

Facebook recognized that what Instagram offered was integral to their product. Instagram could provide a great photo experience by optimizing the media and adding filters. In addition, the experience also catered to a younger demographic, and Instagram was a product built for mobile, an area in which Facebook was trying to strengthen its offering.

There were also brand synergies. By acquiring Instagram, Facebook not only nullified an emerging competitor, it also gained a valuable property that complements, not substitutes, Facebook Ads. The synergies that Facebook believed it could leverage by buying Instagram amounted to a $1 billion valuation.

Talent Acquisitions (Acquihires)

One type of technology-driven M&A is talent acquisitions, or “acquihires.” These deals seek to acquire human capital competitive advantages, not simply market share, supply chain control, or economies of scale.

“In 2016, GM purchased Sidecar, an app-based ridesharing service provider, acquiring not only the company’s software but also 20 employees—including Sidecar’s cofounder and chief technology officer—with digital skills and know-how.”

— Rainer Strack , Susanne Dyrchs , Ádám Kotsis , and Stéphanie Mingardon, BCG, 2017

Talent acquisitions are a special type of acquisition mainly seen in the tech industry and in developed tech hubs like Silicon Valley. Leading companies like Facebook and Google buy startups not because they want the projects but because they want the software engineers.

Digitally talented people are already so highly in demand that many large, traditional companies must reinvent themselves to attract these people. According to experts with BCG—Rainer Strack, senior partner; Susanne Dyrchs, project leader; Ádám Kotsis, expert principal, and Stéphanie Mingardon, senior partner—(quoting a Gartner study), 30 percent of tech jobs will be unfilled because of a lack of digital talent. The BCG experts find that the greatest technology challenge is not data security or the need to invest but rather a lack of qualified employees.

Victor Luckerson, reporter for Time, reports that over 221 startup founders joined Google between 2006 and 2014 because of acquisitions, and 110 founders joined Yahoo.

John F. Coyle, assistant professor of Law, and Gregg D. Polsky, professor of Law at the University of North Carolina, explored the acquihire phenomenon. They found that a company’s main motivations for this type of acquisition include obtaining the services of talented engineers and entrepreneurs at one time, hiring a well-functioning team rather than trying to create one from scratch, and using the talents of its new, experienced employee team to enter a new space quickly despite the buying company’s inexperience in that space.

Before considering an acquihire, it’s important to understand what digital skills the company needs, who is available on the market, where the desired talents can be found, and how to attract and retain them.

For more on human resources and talent management, read our guide on hiring for evolution.

Talent Acquisition Risks and Hurdles

Acquirers can mitigate the risk of acquiring by taking the time to fully understand the capabilities and goals of the people involved. Is there a good fit? What are the short- and long-term benefits? Those involved should also consider the pertinent skills, technology, and synergies. Are they unique? Will they add value under the new, post-acquihire conditions? How will the acquihire impact competitors? How will the new, acquired staff leverage the newly available resources and infrastructure? Is there an opportunity to acquire new patents?

According to Mark Suster, a partner at Upfront Ventures, a significant risk for companies looking to acquire startup talent is that the main team members of the acquihired company may leave the acquiring company after several years.

Metrics for Talent Acquisition or Acquihiring

“It has been reported that a general rule of thumb in Silicon Valley acquihires is $1 million per engineer.”

—John F. Coyle and Gregg D. Polsky, University of North Carolina, 2013

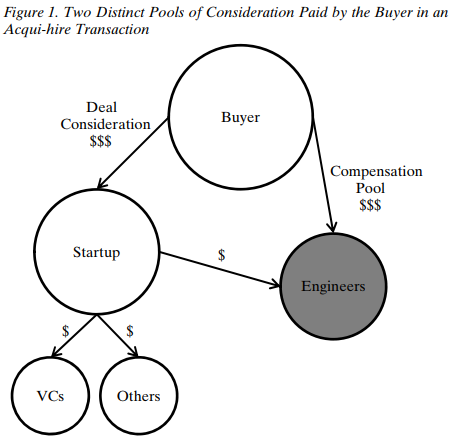

Coyle and Polsky, in their paper “Acqui-hiring,” note two distinct areas of consideration for buyers: the cost of the deal and the cost of compensation. The authors suggest three main metrics that companies in an acquihiring deal should evaluate:

- The number of employees that the buyer wishes to hire

- the value of those employees to the buyer, and

- the value (if any) of the startup’s intellectual property and other assets to the buyer.

Source: Coyle and Polsky, 2013

Another perspective is given by Jessica Verrilli, corporate development principal at Twitter. In an interview with Forbes, she said, “We always start by trying to understand what the team set out to build, what their passion is about. Often, they took a swing at it, maybe they didn’t hit it out of the park, but they have a lot of experience. We try to figure out if we’re trying to tackle that problem. Often the conversation ends there if their passion doesn’t match our product needs.”

The third article in this series, “Managing Tech Deals” Continues the theme of technology-driven M&As. It outlines what actions should occur before and after the deal such as due diligence and integration.

Managing Tech Deals

“The rigor and discipline we use in running our business is key to consistently executing our growth strategy. And we systematically applied the same discipline to our investments, including acquisitions.”

—Pierre Nanterme, Chairman and CEO of Accenture

Before the Deal

Leading up to an M&A deal, valuation is one of the main elements of preparation. But for technology deals where young startups may be involved, Joerg Krings, J. Neely, and Olaf Acker, advisors and practitioners with Strategy&, note that it’s not always so easy to define valuation because there may be no revenue or cash flow on which to base the valuation. Take the Facebook Instagram deal of 2012, for example. In this case, Instagram was a five-year-old startup at the time with no revenue, yet it was acquired by Facebook for $1 billion.

In the case of technology-driven transformation deals where companies acquire as part of a long-term strategy, the price paid might not make sense to investors. Therefore, according to Rob Fisher, Gregg Nahass, and J. Neely, partners with PwC, due diligence is crucial before the deal is made known to investors who may be bemused and less than happy with the high price.

Further adding to the complexity of tech deals is that the due diligence process should be different depending on the type of deal. For example, the scope of due diligence may be limited because the target to be acquired is small, or a billion-dollar company deal may require less due diligence than expected. Big companies may have less to hide than small companies because they have been thoroughly audited or simply because leaders want to keep up the momentum of their innovation work.

James Waletsky, writing for Crosslake, a software consulting firm, lists comprehensive considerations for tech merger due diligence.

Product strategy:

- Does the product strategy fit with the investment company’s growth objectives?

- What are the product strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT)?

- How does the company determine the product roadmap and what will add the most business value?

Product function and quality:

- Are there any problems with the product that may be expensive to fix?

- Does the product fulfill end user goals or is an expensive UI revamp necessary?

Architecture and code:

- Is there anything in the architecture that is an impediment to meeting growth objectives?

- Are there legacy components in the software that require replacement? What will this cost?

- Are there third-party or open source components that may be problematic from the legal or technical perspective?

- Is the code written in a maintainable way such that others can be productive in the code base quickly?

Processes, practices, and tools:

- Are there opportunities for efficiency gains and/or cost reduction?

- Will the existing practices scale appropriately with company growth?

- Are there existing skills gaps that inhibit efficient delivery?

People and organization:

- Are the right people in the right roles to meet investment objectives (particularly leaders)?

- Who is critical to the business and must be retained with the acquisition?

- Are there significant gaps in the organization that must be filled to meet investment objectives?

- Is the level of R&D spend appropriate for the company size? Are there opportunities for reduction?

IT/Operations/DevOps:

- Are there opportunities for cost reduction, such as a move from locally managed resources to the cloud? What is the cost in doing so?

- Is there a suitable business continuity plan in place, and if not, what risk is undertaken and what is required to implement one?

- Are the expenditures reasonable given company size?

- Are deployment practices efficient with minimal risk of human error?

Product support:

- What are the top support call generators that may be indicative of product problems?

- How many escalations make their way to the development team?

Professional services:

- Are implementation times long, potentially indicating lack of configurability/customization in the product?

- Are there opportunities for product enhancement to scale to a larger number of customers requiring less on the services side?

—Source: Waletzky, 2016

According to Waletsky, the risks involved in a tech deal may affect the conditions or price, but the cost of technical due diligence is negligible compared to the potential benefits or costs.

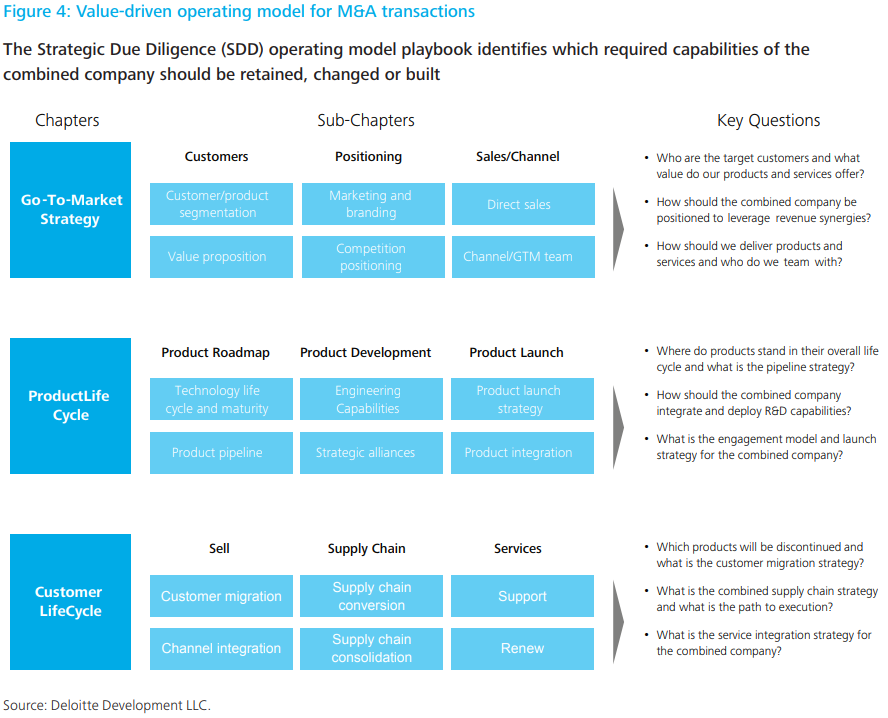

In a white paper, Deloitte has defined a strategic due diligence operation model that can be used for technology deals where a company is targeting companies with dissimilar business models. The model defines some main metrics and identifies which requisite capabilities of the combined company should be retained, changed, or built.

—Image Source: Deloitte

Further Reading: Examples of Due Diligence Process from the Startup World

Some good news for firms needing help with due diligence: venture capitalists have been doing this for a long time. The following are documented examples of due diligence from investors in early stage startups.

After the Deal

Finalizing a deal is half the battle. After the deal, the hard work of integration begins.

Successful integration may rely on the newly acquired management because the technology that is of value is most likely held by a small group of creative leaders. Experienced managers are needed to oversee smooth operations, particularly when a company is buying large operating units.

Relying on acquired management, however, can be a problem. Some of the senior team from an acquired company may decide to leave after the deal closes and look for other opportunities. Given this potential reality, the acquiring company needs to consider how much it will rely on these senior managers and for how long. According to Fisher, Nahass, and Neely, retaining people contractually is often just a short-term solution.

According to Adam Bluestein, writing for Inc., it’s important to hold on to the people who are integral in a smooth transition, such as technology managers and those with crucial knowledge of the acquired technology. The acquirer needs to keep the managers’ hearts in the game by understanding the environment where people are already thriving and reassuring them that the crucial stuff won’t change – or if it will, providing them with the tools and resources to cope. A change management strategy is vital and should be prepared early in the merger decision process to ensure that the associated costs are considered.

Integration Leadership—Don’t Let Cultural Problems Get in the Way

“When you merge cultures well, value is created. When you don’t, value is destroyed…. The game is won or lost on the field of cultural integration. Get that wrong and nothing else matters.”

—George Bradt, Chairman, PrimeGenesis

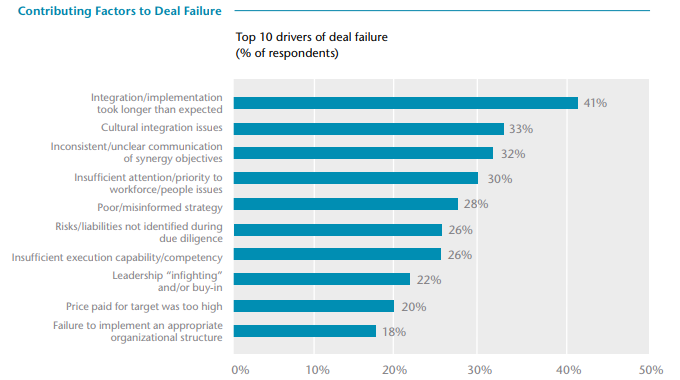

Cultural integration should be part of a change management strategy for mergers. AON found that cultural issues that occur when two entities merge are a main driver of deal failure.

—Image source: AON, 2011

A study by Bain & Company that polled executives who had managed a merger also found that the number one reason given for deal failure was “culture clash.” Team synergies are important and, according to George Bradt, chairman of PrimeGenesis, “Synergies must be created together by teams looking beyond themselves to new problems they can solve for others.”

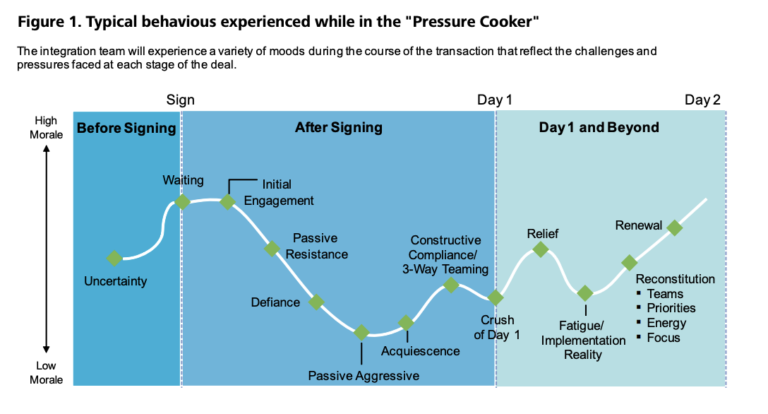

In the graphic below, Deloitte gives excellent insights into M&A from the perspective of those on the ground. The graphic shows how morale is affected from the time before the deal is signed through the post-merger period.

—Image source: Deloitte, 2007

The culture of an organization is largely set by its leadership. But what if that leadership is in transition?

Dale Stafford and Laura Miles, partners with Bain & Company, recommend cultural integration tools that can gauge the mindset and behaviors of employees and encourage better working processes. Managers and leaders can gain a better perspective of how integration is processing or where changes need to be made.

For example, according to Stafford and Miles, videos of employees working together and process flow maps show the different ways a task is undertaken and can guide a discussion of how it should be done in the future. Customer interviews can provide insights for employees into customer perceptions of each organization, and employee surveys can both collect important data and show employees that their opinion matters—but only if the results stimulate action from leaders.

Divestiture for Value Creation

“Treating divestitures as an afterthought is typical. And it’s a shame.”

—Gerald Adolph and Ken Favaro, former senior partners at Booz & Company

Divestment can create value for firms by selling assets that detract from core business functions.

In their HBR article, “Divest With Care,” Gerald Adolph and Ken Favaro, former senior partners with Booz & Company, note that divestiture is often conducted when a firm is restructuring and experiencing a problem. The portfolio examination and the decision to sell assets are made under duress and, consequently, the company is weakened because assets are most likely sold at a lower price than is necessary.

A better way to approach divestiture is through an ongoing, constant process over the long term, which gives a company time to find the right buyer, sell assets at a much better price, and build a higher-quality portfolio.

If done strategically, a divestiture strategy is another tool that companies can use to create value. According to Ernst & Young’s Corporate Divestment Survey for 2019, over 80 percent of companies plan to streamline their operations through their divestment plans over the next 12 months.

Moreover, divestiture can be even more beneficial when done in conjunction with acquisitions. Research by McKinsey’s Sean O’Connell, principal, Michael Park, principal, and Jannick Thomsen, associate principal, shows that companies that both acquire and divest create as much as a 1.5 to 4.7 percentage point higher shareholder return than companies that focus mainly on acquisitions.

Google’s divestiture of Motorola illustrates how a strategic divestiture can be a good move for a company.

Google and Motorola: A Lesson in Strategic Divestiture

In 2011, Google announced the acquisition of smartphone manufacturer Motorola for $12.5 billion. Less than three years later, Google sold Motorola to Lenovo for $3 billion—Google portrayed the deal as a success.

Google’s motive behind the deal was “to help supercharge the Android ecosystem by creating a stronger patent portfolio for Google and great smartphones for users,” according to CEO Larry Page. Rather than maintain the hardware arm’s multi-million dollar yearly operating loss, Google sold off pieces of Motorola while creating a patent portfolio that it is now licensed to Lenovo.

According to Jean Baptiste Su, VP and Principal Analyst at Atherton Research, Google came out ahead, receiving patents valued at $5.5 billion at a cost of around $1 billion.

Further, Google transformed Motorola in the process. The company released two highly rated budget phones during its time at Google: the Moto X and the Moto G. Through this move, Motorola became an attractive acquisition target and quality, budget phones spread the use of Android, a key value driver for Google.

The strategy, though, would not have been successful without careful and deliberate planning, which is increasingly difficult in this climate. How should firms approach divestiture in the fast-moving acquisition climate where technology is playing such a huge role? And what distinguishes a good deal from a bad deal?

Identifying Assets & Divestment

The 2018 Corporate Divestment Study from Ernst and Young suggests that firms should identify how technology is changing their business model. Firms should divest to improve their competitive edge, which means focusing on the core business and having enough liquidity to react to opportunities as they arise.

In 2020, COVID-19 has changed the landscape. The 2020 Corporate Divestment Study from Earnst and Young EY surveyed 25 global activist investors in January 2020, and again in April 2020. The data show that companies consider divestiture more urgent to create focus and simplicity. Over 90 percent of those surveyed recommend that a target company divest non-core or underperforming businesses, up from 64% previously. The timeframe should also be shorter. Before the crisis, 36% of activists suggested a timeframe of within six months for divestiture, but this number has increased to 84%. According to the report, “companies should prepare for investor discussions that focus on how they are responding to the crisis, aligning the portfolio to their core strategy, and other matters such as executive compensation alignment relative to company performance.” There must be a focus on “freeing up capital to build resilience and drive long-term value.”

Reviewing possible divestitures in conjunction with a normal portfolio review means that assets are assessed each year. A scoring system based on algorithms and industry criteria, for example, can rate an asset based on growth potential or to what extent the asset uses resources that might be better allocated to core activities. Low-scoring assets are candidates for divestiture. Managers who have an interest in the asset can present their rationale for keeping the asset, and organization leaders can make the final decision of whether to keep it.

Managers focus on finding a buyer but seldom look at a deal from the buyer’s point of view. Doing so can add clarity to what should be included in the sale in addition to the obvious productive assets.

Preparing for Divestment

Even if companies take a strategic approach to divestiture, problems can arise after deciding what to sell. O’Connell, Park, and Thomsen suggest the following steps when planning divestments:

Prepare for a buyer before there is a need for a buyer. Companies should prepare for possible divestitures before there is a need to sell. An asset could be worth more to one buyer than another because of potential synergies, so waiting to divest until it’s necessary to do so will not provide enough time to find the right deal.

Considering other potential buyers. Evaluating the value of a non-core business is difficult. Executives often overlook an asset’s potential value to others, so external perspectives help (for example, from bankers, potential owners, and industry CEOs).

Invest for mutual success. Deals that aren’t well-prepared can be costly for both the buyer and the seller, and the outcome of divestiture for both parties is linked. Firms, then, should prepare divestiture candidates for post-deal success just as much as they prepare for price negotiations by understanding the asset’s potential sources of value. Giving the new owners supporting documentation, strategy suggestions, or data on potential improvements can increase the likelihood of a successful transaction for both parties.

Commit resources for post-deal success. Ensure there is the right managerial talent and supporting knowledgeable staff. According to Fubini, Park, and Thomas, partners with McKinsey, managers tend to think about the separation process as secondary, assuming they can separate a business and worry about stranded costs later. It’s also important to consider the internal conflict that can occur between outgoing managers and those who are staying. Finally, ensure that management and the board don’t get so caught up in the sale that the core business is neglected and suffers.

—Source: O’Connell, Park, and Thomsen of McKinsey, 2015

Case Study on Cisco

Because the models for M&A leadership success vary greatly depending on the context and the personality of the leader, we present a summary case study on Cisco, a company that has mastered the art of acquisition. We also provide insightful quotes from business leaders who describe their own experience with mergers.

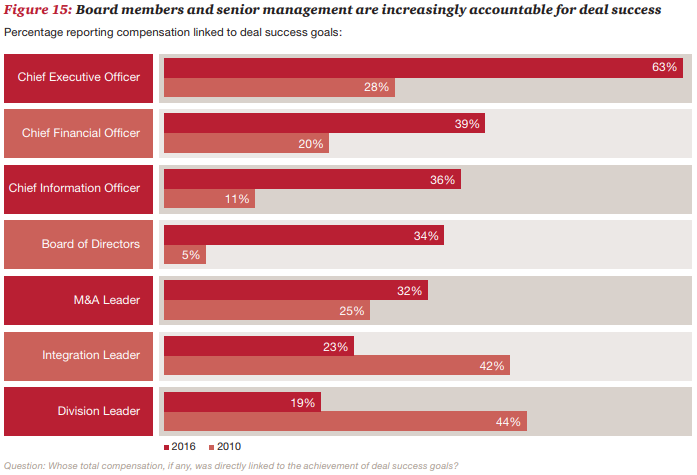

Leadership is paramount during times of upheaval, providing direction and strategy during mergers and determining personnel policies that can maintain morale. The CEO is front and center, but the accountability of all C-suite executives with respect to deal success has changed over time.

The graphic below, developed by PwC, shows the accountability of various managers and C-suite executives in merger activities. Since 2010, the influence of CEOs on deal success has more than doubled, and the influence of the CIO has tripled.

—Source: PwC, 2017

There is no one-size-fits-all approach when it comes to managing a merger; so many variables apply depending on the context, the culture, and the personalities involved. Rather than follow “how to”’ guides, it is more valuable to study the past experiences of others and learn from their successes and mistakes.

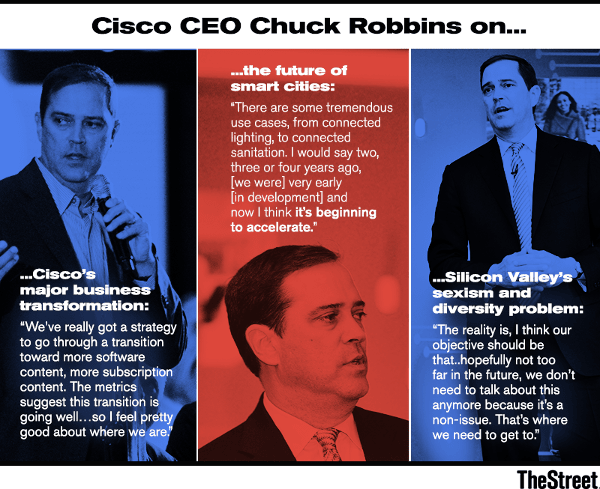

Cisco has mastered the art of acquisition having bought over 100 companies within 13 years. The following case study explains the company’s strategy and the rationale behind some of the deals. Cisco provides an excellent model for deal management for technological growth.

“We make acquisitions that get us into very new markets …. And we also make acquisitions in areas that are transitions within markets we already participate in. Meraki is the transition with cloud networking. Insieme Networks was about SDN in the data center. Cisco has a proven model for driving a lot of value in markets we understand that are undergoing transition, and that’s what we plan to do with Viptela.”

—Rob Salvagno, head of corporate development, Cisco.

Cisco is one of the leading companies in technology and a leader in M&A strategy. The company bought more than 100 companies between 1993 and 2016. Five of their biggest deals were OpenDNS ($635 million), Meraki ($1.2 billion), Sourcefire ($2.7 billion), NDS Group ($5 billion), Jasper Technologies ($1.4 billion), and Lancope ($452.5 million).

Cisco defines its growth strategy as one that identifies and drives market transition. The company separates acquisitions into three segments: market acceleration, market expansion, and new market entry.

The company focuses on integration by investing in dedicated integration resources across the company. For Cisco, integration is a process that starts with the entire acquisition strategy. The company seeks acquisitions based on a strong business case but also a shared business and technology vision.

“We invest $100 million to $200 million in startups a year. Situations like AppDynamics and Meraki show we can move at a pace that is really unequal by other people and that we have a playbook to make those successful that is also unrivaled. When we acquired Meraki four years ago [for $1.2 billion], it was at a $100 million bookings rate. Today it’s exceeding a $1 billion booking rate. We can anticipate where the market is going because of that lens we have as investors. We pioneered the spin-in model and did our first set of divestitures, and we are beginning to build that muscle up.”

—Rob Salvagno, head of corporate development, Cisco.

—Image Source: The Street, 2017

—Image Source: The Street, 2017

“A lot of what I’m focused on is how we drive the innovation ecosystem to complement Cisco’s traditional engineering motion, how we drive external engagement with startups, how we look at opportunities to augment what we’re doing inside the company through acquisitions, and how we develop next-generation partnerships at global scale, like we have with Ericsson and Apple.”

—Hilton Romanski, chief strategy officer, Cisco

“Our Integration Team is a unique project office that allows us to successfully integrate the acquisitions we make as well as run complex programs related to our next-gen partnerships. As you know, we make between eight and 12 acquisitions a year, so having a talented team in place to help support M&A is crucial. Having a dedicated team in place to help us plan for, manage, execute, and then look back on our deals is a strategic differentiator for Cisco.”

—Hilton Romanski, chief strategy officer, Cisco

What are the reasons behind some of Cisco’s acquisitions?

The acquisition of Observable Networks

“The acquisition of Observable Networks supports Cisco’s strategic transition toward software-centric solutions that deliver predictable recurring revenue. Together, Cisco and Observable Networks will extend the Cisco Stealthwatch solution into the cloud with highly scalable behavior analytics and comprehensive visibility. The acquisition also extends Stealthwatch to the Mid-Market customer segment.”

—Cisco, 2017

The acquisition of MindMeld

“MindMeld believes that a truly human-like conversational experience requires highly customized and domain-specific trained language models. By focusing MindMeld’s capabilities on Cisco’s specific collaboration domains, we believe we will enable a user experience that will be differentiated from anything that exists in the collaboration space today.”

—Cisco, 2017

The acquihire of an Advanced Analytics team from Saggezza

“By adding a team of analytics experts, Cisco will augment our current analytics capabilities so we can improve insights into network performance and automation, accelerate Cisco DNA development efforts, and enhance our cloud and SaaS analytics offerings. The acquisition is a reflection of our strong belief that analytics will play a critical role in the building of next-generation networks designed for an era of cloud, IoT, and pervasive security threats.”

—Cisco Advanced Analytics Team from Saggezza, 2017

“This acquisition is aligned to Cisco’s strategic goals to develop innovative big data analytics and cloud technologies while also cultivating top talent.”

—Cisco Advanced Analytics Team from Saggezza, 2017

The acquisition of AppDynamics

“Cisco and AppDynamics’s capabilities are very complementary. Cisco delivers comprehensive data collection and insights in the datacenter, network, and security domains. While AppDynamics bring the industry-leading solutions for application, end user, and business transaction insights together, Cisco and AppDynamics will break the silos of application, infrastructure, and security domains to help organizations evolve from managing IT performance to managing digital business performance and business transactions. As part of Cisco, AppDynamics will complement current Cisco product initiatives to provide end-to-end IT intelligence platforms that offer customers holistic visibility, correlation, and insights across IT domains—from the code to the end user and everywhere in between.”

—Cisco, 2017

“The acquisition of AppDynamics is part of Cisco’s broader strategy to drive growth for the company, our customers, and our partners.”

—Cisco, 2017

Insights From M&a Strategy Leaders

Cisco is a pioneer in M&A, but there are countless other leaders and experts. This section is composed of direct quotes from top executives who are handling the M&A activities of some of the biggest companies in the world.

Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Facebook

Mark Zuckerberg gave rare insight into how he approaches acquisitions during public testimony in a Dallas courtroom, and his responses were reported by Alex Heath, writer for Business Insider.

On building long-time relationships before acquisitions

“I’ve been building relationships, at least in Instagram and the WhatsApp cases, for years with the founders and the people that are involved in these companies … when it became time or when we thought it was the right time to move, we felt like we had a good amount of context and had good relationships so that we could move quickly, which was competitively important and why a lot of these acquisitions, I think, came to us instead of our competitors and ended up being very good acquisitions over time that a lot of competitors wished they had gotten instead.”

—Mark Zuckerberg, CEO, Facebook, Business Insider, 2018

On having a shared vision

“The most important thing was aligning and getting excited about a shared vision and about how we’re going to work together. Or, if they built the hardware and we built the experiences, how that could be better than either of us working separately.”

—Mark Zuckerberg, CEO, Facebook, Business Insider, 2018

Peggy Johnson, EVP of Business Development at Microsoft

In an interview, Peggy Johnson, EVP of business development at Microsoft, gives insights into Microsoft’s M&A strategy. She discusses the type of companies and the deals they pursue, how the M&A team functions in Microsoft, and the areas they target.

On looking at one main indicator

“Deals are always a bit lumpy. We look at: Is it solving a problem for us? And if it does, we move to acquisition.”

—Peggy Johnson, EVP of business development, Microsoft

On M&A team organization

“M&A at Microsoft is a team sport for the senior leadership group. They’re all involved in it, and we all play different roles. My role is the first centralized business development role at Microsoft. The team previously had been embedded in the product groups …. Now we can sit across all the major groups of the companies, and we have much more flexibility.”

—Peggy Johnson, EVP of business development, Microsoft

On valuation

“Valuations are always much-debated. I try to center on what is the value to us. Is it solving a problem for us? If it is, we find a way to proceed. If the valuation has been overhyped on something and it doesn’t make sense, we won’t. It’s very simple for me. I tend not to worry too much about the valuation. It’s really what the value is to us.”

—Peggy Johnson, EVP of business development, Microsoft

On ROI

“We have to balance strategic opportunities versus ROI. We ask the team to show us the path to commercialization and path to ROI. We are very disciplined and rigorous in our approach and super focused on monitoring the investment. We do it all within my team – we don’t rely on the product groups to track the investments.”

—Peggy Johnson, EVP of business development, Microsoft

John Somorjai, EVP of Corporate Development and Salesforce Ventures

In an interview with Fortune magazine, John Somorjai, EVP of corporate development and Salesforce Ventures gives insights on Salesforce’s M&A strategy, their areas of focus, how their strategy is driven by customer needs, and how they approach valuations.

On accessing the best technology

“AI, mobility, and big data are driving a lot of the profound changes you’re seeing in businesses overall. We found we needed to accelerate our efforts to make sure we were accessing the best technology we could deliver to our customers quickly and also bring in some really great talent, especially in the AI space.”

—John Somorjai, EVP of Corporate Development and Salesforce Ventures, 2017

On M&A approach

“We generally take the same approach each year. Because we’re product-focused and product-driven, we’re reactive to the environment. When we see products or developments or large companies that are solving a problem in a new way, that drives M&A interest.”

—John Somorjai, EVP of Corporate Development and Salesforce Ventures, 2017

Don Harrison, Head of Corporate Development, Google

In an interview with Fortune, Don Harrison who heads up corporate development at Google, gives insights on Google’s M&A strategy, the company’s priorities, its focus on AI, and the approach to divestitures.

On valuation metrics

“It’s very hard to apply valuation metrics to AI. These acquisitions are driven by key talent — really smart people. It’s an area I’m focused on and our team is focused on. The valuations are part and parcel of the promise of the technology. We pay attention to it but don’t necessarily worry about it.”

—Don Harrison, corporate development, Google

On the most important elements for deal success

“M&A will never be 100 percent successful, and we learn from every deal we do. And so not to pick on any specific deal, but I’ve learned, based on relative success of deals we’ve done in the past, to make sure the key leaders at the company share a vision with the founder, that the strategy drives the M&A, as opposed to the M&A driving the strategy, and that we have good support mechanisms for these companies after they come in.”

—Don Harrison, corporate development, Google

On divestiture

“I think Niantic [creator of the popular Pokémon Go game] is our most famous divestiture. We have done divestitures, and I’m a fan of us thinking about that actively. Google is still very much in growth mode. When I look at Sundar’s and Alphabet’s strategy, I see broadening the vision. We should continue to make good bets across a variety of areas and recognize that some of those aren’t going to succeed, and divestiture becomes a good home.”

—Don Harrison, corporate development, Google

Robert Weiler, VP of Oracle’s Global Business Units (GBU)

In an interview with Fortune, EVP of Oracle’s Global Business Unit, Robert Weiler, gives insights into Oracle’s M&A strategy, how their Global Business Unit works, and what they look for in an acquisition.

On small deals

“But while Oracle is no stranger to making big purchases at opportune times, such as its $10.3 billion acquisition of PeopleSoft in 2004 or its $8.5 billion acquisition of BEA Systems in 2008, the bulk of its deal flow will most likely remain modest in its size and narrow in its scope. Such small deals usually draw yawns from financiers (and news editors), but it is all part of Oracle’s overall business strategy to dominate and control the most profitable industry verticals in the business software (read: cloud computing) world, all without drawing attention to itself or its affiliates.”

—Robert Weiler, EVP Global Business Units, Oracle

On M&A strategy and GBU structure

“The strategy, which Oracle co-founder and executive chairman Larry Ellison devised years ago, involves first acquiring companies that make software considered a “must-have” for a particular industry. The acquired companies are then placed into semi-autonomous business groups called Global Business Units that are industry-specific (e.g., financial services or health sciences) and have their own organizational structure (each has its own general manager, development, sales, marketing, consulting, and M&A strategy). The GBU structure now encompasses seven business units made up of 33 acquired companies with a total deal value of around $15 billion. Oracle will expand into any industry vertical it thinks it can come to dominate and can snap up a company in the blink of an eye.”

—Robert Weiler, EVP Global Business Units, Oracle

On integrating the acquired team

“Larry’s view was that you lose domain expertise in big organizations because it scatters and naturally dilutes. You come back two years after an acquisition and you can’t find the company, the nucleus that made the company great. So, he said for industry applications, “I am going to keep that nucleus.” As such, when we acquire a company, the development team and sales people are still working on the same thing. Occasionally, we’ll change some things within a vertical, but they’re all around the same passion and solution.”

—Robert Weiler, EVP Global Business Units, Oracle

Apple

Bloomberg gives an overview of Apple’s M&A strategy, the type of companies it buys, and the composition of its deals team.

On Apple’s deals team

“Apple’s deals team is composed of about a dozen people under former Goldman Sachs banker Adrian Perica, and most acquisitions take place at the behest of the company’s engineers. Product managers usually meet every month with Perica’s team members to identify targets with attractive technology or talented engineers, according to a person familiar with the process.”

—Alex Webb and Alex Sherman, Bloomberg, 2017

Hopefully, this guide has expanded your knowledge and answered questions on M&A and divestiture, particularly technology-driven deals in today’s dynamic business environment. We value your opinion and feedback and welcome any comments, suggestions, and additions to this material.

HowDo Can Help You

HowDo has been on both sides of the table and is happy to help you with your M&A. We have deep experience in:

- Competitive analysis

- Emerging technology sector strategies

- Due diligence of product, technology and team,

- Deal negotiation

- Post-purchase integration of product, technology and team

- Culture mapping and transitioning of team

Contact us today to learn more.