Research and Development

You will look at the ways that market leaders are conducting Research and Development (R&D), examine case studies, and explore actions for today’s forward-thinking firms.

In this training, you will

- Explore the state of modern research and development (R&D).

- Learn how Amazon and Google’s approaches R&D.

- Learn metrics for R&D.

- Explore best practices for R&D.

Skills that will be explored

About the Guide:

Discovering a breakthrough product makes for transformational innovation; a novel concept can disrupt an industry in one fell swoop and catapult a firm to market leadership. It is the dream of innovators.

Frustratingly, transformational innovation is also elusive. According to Jay Terwilliger, writer for Creative Realities, Inc., an innovation consulting firm, “transformational innovation is exceedingly rare. Think about it: how many truly new-to-the-world ideas happen in a year? In a lifetime? Not many!”

The scarcity of breakthroughs is largely because few occur organically. Breakthroughs occur with hard work, focus, and often long-term effort to explore a vision, solve a problem, or tweak an existing prototype, and that’s all before the product is successfully brought to market. So, what is it that keeps firms investing heavily in R&D and pursuing ever-distant, world-changing concepts?

Perhaps the more realistic purpose of R&D investment is to sustain a competitive market position in an environment where advances are coming thick and fast. R&D investment builds the moats, through IP and operational efficiencies, that can secure a firm’s future amidst the seemingly infinite barrage of competition from corporates and startups alike. That is what R&D means to firms and why it is so important to them. Fall behind and fall out of the market.

Research and development (R&D) has existed since the first corporation. Defined by Investopedia as “the investigative activities a business conducts to improve existing products and procedures or to lead to the development of new products and procedure.”

Some of the world’s most recognizable innovations are products of R&D labs. In the past, AT&T’s Bell Labs gave us the transistor and the cellular telephone. Today, we see R&D products in the form of Amazon Echo, Google’s autonomous car unit, and digital health wearables that measure heart vitals, temperature, and can track when someone falls. The breakthroughs are irrefutable — but what is less difficult to quantify, is how best to pursue R&D. What strategies work? How much should a firm invest in R&D? What factors lead to breakthroughs or transformation innovation?

The following two articles attempt to answer the questions that today’s CEOs and entrepreneurs have concerning the value of R&D, best practices to follow, and how to develop a focused plan that builds creativity and an R&D portfolio while technology is rapidly advancing around them.

The State of Modern R&D

“The enterprise that does not innovate ages and declines. And in a period of rapid change such as the present, the decline will be fast.”

— Peter Drucker, Legendary business author and management consultant

The appetite for R&D investment is on the rise spurred by technology advancements such as artificial intelligence, AR and VR, robotics, and 3D printing. All of these technologies and more are paving the way for new products that are changing the way we live and work.

This appetite is reflected by huge R&D corporate budgets. Specialist R&D tax advisers Swanson Reed reported that, in 2015, business R&D spending reached $356 billion in the United States, an increase from the previous year of close to 5 percent. Swanson Reed also reported that companies are also investing more of their own funds in R&D, particularly manufacturing companies, which accounted for over 60 percent of domestic R&D spending.

This torrent of R&D activity, somewhat based on the belief of many that R&D is the way to market leadership, belies the fact that no scientific correlation has been found between R&D expenditure and company performance.

According to Tendayi Viki, Managing Partner at Benneli Jacobs, a strategy and innovation consultancy firm, the belief that R&D spending is somehow connected to increased innovation, revenue growth and profits is just a presumption.

PwC’s Strategy& has published the top 1,000 most innovative companies in its annual report for the past 12 years or more. Interestingly, each year, the top 10 most innovative companies are rarely the top 10 spenders on R&D.

So, why are companies investing so heavily in a strategy that has no empirical connection to profits?

Fundamentally, companies spend on R&D to stay ahead of the curve. While sales and operations keep companies afloat, R&D is among the tools that companies must leverage to evolve and prepare for the future. Unlike some of the other tools in the growth and innovation arsenal focused on discovering and fast-following opportunities, R&D is a long-term strategy that creates original moats supported by intellectual property and unique efficiencies. While spending on R&D may not bring the instant lucrative breakthrough, it keeps a company on a level playing field with its competitors as technology and industry practices advance (in addition to providing tax benefits.)

How Big Tech Does R&D

While corporations are spending more than ever on R&D, at the same time, R&D productivity on a national level is on the decline. Further, The United States has dropped out of the top 10 in Bloomberg’s Innovation Index.

While R&D is struggling on a macro-level, the leaders in the modern economy — “ Big Tech” (Amazon, Google, Microsoft, Facebook, etc) — all have fruitful R&D programs. In the following section, we dive into examples of Big Tech R&D strategy.

Choosing an R&D strategy requires following a model, preferably one based on quantifiable data. One problem that Knott’s RQ highlights is the difficulty inherent in determining the impact of R&D.

R&D is difficult to benchmark among firms because R&D practices and strategies are unique to individual firms. For example, Amazon’s practice of expensing R&D hides the firm’s economic earnings. According to Valens Research, for Amazon, “GAAP guidelines that require R&D costs to either be expensed or capitalized from acquisitions as in-process, or written off later leads to a low-quality earnings number and an unreliable balance sheet.”

Therefore, comparing the results of R&D across different companies and industries to find patterns, as Knott did, is troublesome. For example, tech companies spend more on R&D than any other companies in the United States (23 percent in 2017, according to PwC). In contrast, consumer packaged goods (CPG) companies are spending a fraction of that (3 percent in 2017, according to PwC), and 60 to 80 percent of their budgets go towards renovation and maintenance of existing products.

Source: PwC Innovation 1000, 2017

Zoom in on tech companies and the picture becomes even murkier. As a percentage of revenue, firms such as Apple spend very little on R&D, 3 percent, while Facebook spends 21 percent, according to Alice Truong, reporter for Quartz.

Source: Truong, 2014

Comparisons of industries and firms are problematic because there are so many variables.

This lack of relationship doesn’t mean R&D shouldn’t be pursued – Amazon, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft all have high (and increasing) R&D expenditures and are also considered some of the most innovative in the world. Although R&D is a highly individualized process and trends cannot be easily measured on a macro-level, we can look to these big tech firms as a valuable source of examples of what good R&D looks like.

R&D Case Studies

Headlines exemplify the race to the next breakthrough transformational that is ongoing among the market leaders. For example:

“Google continues its explosive spending on R&D,” Chris O’Brian, VentureBeat

“Amazon Is Spending Insane Amounts of Money on Research So That It Keeps Crushing Rivals,” Lindsay Rittenhouse, The Street

“Apple R&D Spend Exceeds $3 Billion for the First Time, up $410 Million from September,” Mikey Campbell, Appleinsider

“Alibaba is Doubling its R&D Spend to $5 billion — But that’s Less Than a Third of What Amazon Spends,” Rani Molla, Recode

Here’s a closer look at two of the most interesting R&D leaders, Amazon and Google, and their approaches to R&D.

Amazon: R&D as a Culture

Amazon’s most visible efforts are found in Lab126, an R&D subsidiary based in Sunnyvale, California. This is the branch responsible for all of the hardware products tied to Amazon — the Kindle, Echo, and the [ashamed] Fire Phone. The lab continues to push out devices, launching the Echo Show, Echo Spot, and redesigning the Fire TV and original Echo — all within a matter of months.

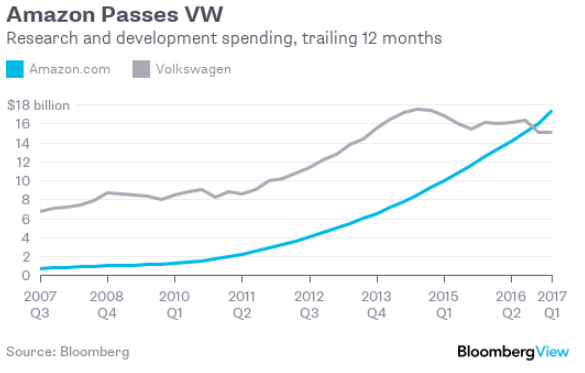

According to Dan Gallagher, reporter for The Wall Street Journal, Amazon spent over $5.5 billion in the second quarter of 2017, which was a year-over-year increase of over 40 percent, and the firm shows no signs of slowing its R&D expenditures.

Amazon’s profitability has benefited from its growing cloud business, which has provided some buffer against the R&D spending that does not provide breakthrough products. But Amazon persists in R&D even in markets where it is already beating its rivals.

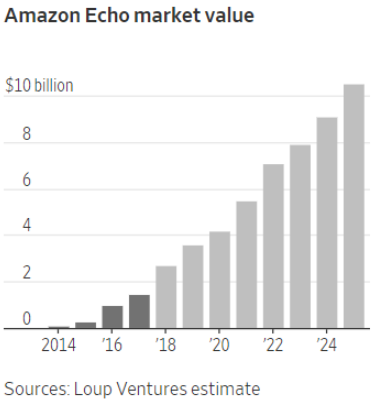

Amazon’s Echo dominates the voice-activated speaker market yet the company has issued a newer version that is priced 45 percent less than its predecessor, a move expected to increase the market value of Echo five-fold by 2026. And, referring to the Alexa platform, Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos said: “expect us to double down.”

To better understand the origin of Amazon’s R&D strategy, we can look at Bezos’ 2010 Letter to Shareholders. Bezos explains why Amazon aggressively invests in technology, and it goes beyond Lab126:

“All the effort we put into technology might not matter that much if we kept technology off to the side in some sort of R&D department, but we don’t take that approach. Technology infuses all of our teams, all of our processes, our decision-making, and our approach to innovation in each of our businesses. It is deeply integrated into everything we do.” Bezos adds, “these techniques are not idly pursued – they lead directly to free cash flow.”

This quote explains the importance of R&D activities while at the same time highlighting aspects of Amazon’s culture: innovation and growth are built into every segment of the company, not just R&D.

Amazon’s R&D strategy suggests many best practices. Here are two:

- Use technology throughout an organization not just as part of partitioned R&D activities.

- Recognize core competencies and maximize them.

Google X: Searching for Radical Breakthroughs

R&D, rather than siloed off to a separate corporate arm or department with a separate budget, is often tied throughout a company’s operations, as is evident in Bezos’ letter to shareholders. At the same time, R&D can also be responsible for many of these companies most ambitious (and sometimes bizarre) projects that are not part of a firm’s core competencies.

Google has a sandbox meant solely for these types of projects — “X.” X, aptly subtitled, “The Moonshot Factory,” focuses on radical projects that are 10 times better than any existing solution. Why? According to Astro Teller, director of Google X, a 10 times improvement is often easier than a 10 percent improvement.

Teller explains that when looking for a 10 percent improvement, a company is tied to existing technologies and solutions, but when shooting for 10 times, anything goes. Moonshots are at the intersection between a huge problem, a radical solution, and a breakthrough technology.

The most visible effort from Google X is its autonomous car project, spun out as an Alphabet Subsidiary called Waymo. The Waymo moonshot is framed as follows:

Problem: Close to 1.25 million people die on roads every year globally, and 94 percent of those accidents are caused by human error.

Radical Solution: What if cars could drive people safely from point A to point B at the push of a button — without needing a human to take over driving at any time?

Breakthrough Technology: Vehicles could have built-in sensors to detect pedestrians, cyclists, vehicles, road work and more from a distance of up to two football fields away in all directions. Smart software could predict the behavior of objects and road users to help the vehicle navigate the vehicle safely through everyday traffic.

— Source: Waymo, 2017

Today, Waymo is the frontrunner in the autonomous car space. Lucinda Shen, reporter for Fortune, writes that analysts from Morgan Stanley have estimated the firm’s value at or near $70 billion dollars. Waymo struck a partnership in 2017 with Lyft, which has the second biggest volume in U.S. ride service. Further, Shen reports that Waymo and Honda are close to finalizing a deal to build automated delivery vehicles, which is a significant commercialization push from a giant that generates around 90 percent of its revenue from advertising. But this success doesn’t come without struggles.

Google X kills projects — a lot of them. For every Waymo or Verily (Google X’s life science spinoff), there are countless projects that don’t make the cut. “We killed over 100 investigations last year alone,” Teller states in a 2017 Ted talk.

The organization moves quickly, fails a lot, and iterates based on feedback. Teller describes the thought process behind the killing of their buoyant cargo ship project:

“However cheap they would be in volume, though, we found out it was likely to cost close to $200 million for the R&D and materials to design and construct the first one. Since X is structured around tight feedback loops of making mistakes, learning, and new designs, $200 million is way too expensive for us to get the first data point on whether we’re on the right track.”

— Astro Teller

This cost-benefit analysis must run through every decision, from the mundane to the risky. Both organizations, Google and Amazon, exemplify a mastery over the R&D portfolio, allocating resources to both incremental and radical advancements.

Google’s R&D strategy also suggests best practices that the lay company can apply:

- Balance risk and potential breakthrough goals with investor and stakeholder tolerance.

- Develop a cut-throat portfolio selection strategy.

Metrics and Best Practices for R&d Optimization

“Chief executives struggle to make the case to the Street that their managerial actions can be relied on to yield a stream of successful new offerings…The pursuit of the new feels haphazard and episodic.”

— Bansi Nagji and Geoff Tuff, partners at Monitor Group

Ninety-nine percent of mature companies fail when entering new markets, which makes bold R&D ventures both high risk and costly. Long-term investment in R&D can yield gains over a prolonged time horizon, but that can be a hard sell to investors and board members who seek short-term results. However, CEOs and businesses can develop an R&D strategy that straddles the need for long-term investment and growth with governance, financial, and competitive pressures.

The way that a portfolio is managed reflects a company’s organizational culture and infrastructure. If a company doesn’t already have a culture that accepts risk or an infrastructure that shields labs from day-to-day operations, then robust, data-driven assessments (ROI, value assessments) will be the only way to convince stakeholders to invest. But, this is short-sighted.

For more on culture, see our guide on building a culture of innovation with examples from Microsoft, Netflix, Facebook and more.

Bansi Nagji and Geoff Tuff are partners at Monitor Group and leaders of the firm’s global innovation practice. They have researched best practices for R&D portfolio management considering the pressures of market expectations, investors, and global competition.

Nagji and Tuff discuss three types of R&D, or innovation, that they have incorporated into an Innovation Ambition Matrix: core innovation, which is based on optimizing existing products; adjacent innovation, which expands existing business and products; and transformative innovation, which aims to develop breakthrough products.

The authors developed the Innovation Ambition Matrix to help companies in their decisions to allocate funds to R&D and growth initiatives, and they explain it in detail in their article in the Harvard Business Review.

Nagji and Tuff explain that for some projects, estimating returns to develop an R&D portfolio is easy. Traditional financial metrics such as net present value and ROI are applicable and straightforward when evaluating R&D aligned with the core business. These calculations assume variables such as adoption rates and price points of new products or ideas, which is entirely feasible for core products.

However, where transformation efforts are concerned, making such assumptions is impractical. Some products are abstract, some products build platform stickiness and, in some cases, to quote the late Steve Jobs, “People don’t know what they want until you show it to them.” Estimating transformational ROI and attempting data-drive assessments, in this context, is pointless. Companies need to think differently.

The Innovation Ambition Matrix

Source: Nagji and Tuff, 2012

The matrix helps managers to assess ongoing R&D initiatives, the number of initiatives and the level of investment. It provides a way to shape the overall ambition for the company’s innovation, whether it be short or long-term small projects that complement existing products, or high-risk efforts that might offer a breakthrough or a bigger payoff.

But there’s an additional problem in addition to the difficulties in valuing transformational R&D strategies.Nagji and Tuff found that, because chief executives often do not have a strong grasp of the myriad initiatives that might already be underway in their organizations, R&D can be haphazard and episodic.

According to Nagji and Tuff, “the companies that have a strong track record of creative endeavors articulate a clear R&D ambition, balance core and transformational ventures, and have the infrastructure, tools, and capabilities to manage and integrate initiatives.”

Determining R&D Focus

Beyond the core, adjacent, and transformational lens introduced above, firms must decide on where to focus their R&D efforts in relation to their product offerings. For the majority of companies, the focus has shifted towards software. From Strategy&’s, “Software as a Catalyst” report:

“Most of the world’s major innovators are in the midst of the same transformational journey. R&D is shifting more and more toward developing software and services. Software increasingly carries the burden of enabling product differentiation and adaptability, and enhancing customer experiences and outcomes.

This transition is for a good reason — it’s the same tactic that has skyrocketed tech giants ahead of the competition. According to Ben Thompson of Stratechery, “while digital infrastructure obviously needs to be maintained, by-and-large the investment reaps dividends far longer than the purchase of any physical good.”

— Strategy&

Thompson goes on to provide examples of the strides made due to tech giants’ R&D:

It was expensive to develop mainframes, but IBM could reuse the expertise to build them and most importantly the software needed to run them; every new mainframe was more profitable than the last.

It was expensive to develop Windows, but Microsoft could reuse the software on all computers; every new computer sold was pure profit.

It was expensive to build Google, but search can be extended to anyone with an Internet connection; every new user was an opportunity to show more ads.

It was expensive to develop iOS, but the software can be used on billions of iPhones, every one of which generates tremendous profit.

It was expensive to build Facebook, but the network can scale to two billion people and counting, all of which can be shown ads.

Aside from a general preference for software, metrics can help guide firms efforts and spending when creating a research and development portfolio.

— Ben Thompson, Amazon Go and the Future, 2018

Where Companies Fail in Selecting an Optimal R&D Portfolio

R&D, like any investment, should maximize returns over time. All too often, governance, stakeholder, and consumer pressures mean that short-term developments are prioritized over radical change that requires a longer time horizon. A study by Rachelle Sampson and Yuan Shi of the University of Maryland found a correlation between failure to invest in the long term and a decrease in a firm’s innovativeness.

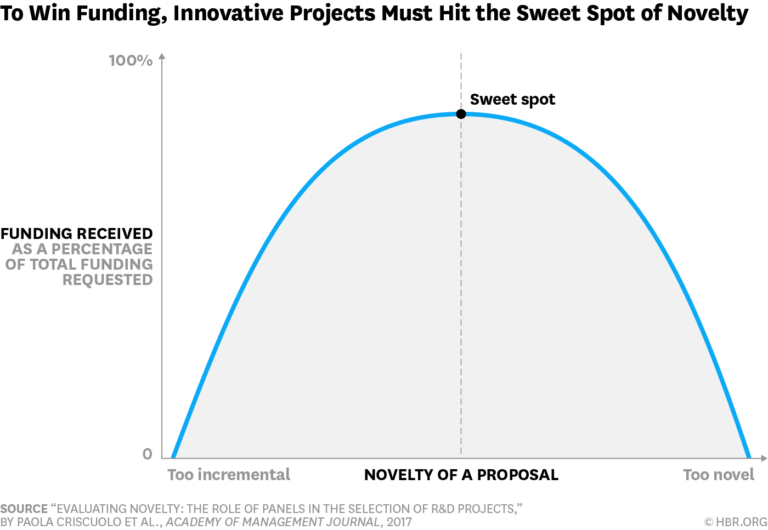

But the issue isn’t as simple as telling executives to focus more on the future. There are many other factors that come into play when allocating funding to projects. A study by researchers Paola Criscuolo, Linus Dahlander, Thorsten Grohsjean, and Ammon Salter published in the Academy of Management journal found that many R&D funding decisions were undermined by simple human bias:

“The Biases That Keep Good R&D Projects from Getting Funded (…) R&D selection is not always based on objective estimates of a project’s costs and returns. We found that funding decisions in this organization were influenced by how novel a project seemed. Proposals that were deemed either too novel or not novel enough got little or no funding.”

— Criscuolo, Dahlander, Grohsjean and Salter

The illustration above developed by Criscuolo, Dahlander, Grohsjean, and Salter illustrates how R&D selection is not always conducted scientifically. How can this problem be overcome, and a best practice instituted for portfolio selection? Metrics can serve as the guide.

Metrics for R&D

R&D Portfolios

A portfolio for R&D should reflect a company’s position regarding risk and reward. According to Nagji and Tuff, that means building a portfolio that produces the highest overall return and that meets its appetite for risk.

In Managing Your Innovation Portfolio, Bansi Nagji and Geoff Tuff state that a combination of noneconomic and internal metrics can best assess transformational efforts in their early stages. For example, one achievement of an R&D initiative is that a team learns by exploring and experimenting.

“For example, what if the only hurdle an initiative must clear to receive continued investment is that the company is likely to learn (not earn) from it? That is how Google has assessed transformational innovation from the start,” state Nagji and Tuff.

This concept of valuing organizational learning can be a tough sell, but it’s an important one. The most innovative companies are all known for their tolerance of failure and their belief in building a learning organization. This is central to their cultures that fuel growth and innovation.

Metrics to measure learning are, therefore, crucial because when ROI is not a persuasive metric where investors are concerned – and it is not where transformational R&D is concerned – much of a company’s value is realized in the learning that is achieved and the knowledge and talent amassed in employees based on their professional experience both inside and outside the organization.

A more quantifiable, traditional measure is the number of patents.

Measuring Patents

The number of patents is one measure of R&D efficacy that has persisted for years. On the surface, this makes sense. Many researchers within R&D departments come from academic backgrounds and published papers are signals of success. However, this measure is the equivalent of a blunt instrument when assessing a firm’s innovativeness.

Patents are subject to a number of confounding variables. For instance, if the firm partners with a university, there is a higher propensity to patent. If the firm conducts international business, there is a higher propensity to patent. Further, tech companies are moving towards open-source software development, resulting in a lower propensity to patent. These factors hinder patents’ value as a measure of communicating value to stakeholders or the greater market.

These limitations have led experts to creating novel metrics to better address the complexities of R&D success.

Modern Metrics for R&D

According to Anne Marie Knott, professor in Business at Washington University’s Olin Business School in St. Louis and author of the book “How Innovation Really Works,” “despite all the experts dedicated to helping companies innovate, the money companies spend on R&D is producing fewer and fewer results. In fact, my research shows the returns to companies’ R&D spending have declined 65 percent over the past three decades.”

To arrive at her conclusions, Knott used a metric that she developed to measure R&D productivity – the output that firms get in return for innovation inputs – which she calls research quotient, or RQ. This metric is a useful one for managers trying to secure R&D budgets from decision makers and investors. RQ calculates the percentage increase in revenue from a 1 percent increase in R&D spending across the organization (for the theory of RQ, see “Estimating Firms’ Research Quotient (RQ)”.)

The decline that Knott sees in the RQ of companies mirrors the overall decline in GDP growth in the United States for the past 30 years.

Knott suggests three theories that might explain the declining trend in returns from R&D spending. The first is that R&D work is more difficult in the current age because the best and most obvious ideas are quickly discovered and the remaining ideas are less novel or groundbreaking. The second theory is that there are diminishing returns to investment in research labor – more researchers decrease the number of innovations per worker due to duplicated efforts.

But Knott does have another explanation, which is that companies may have become worse at R&D.

Knott researched the financial data of all publicly traded U.S. firms for the past 40 years and found patterns related to industry technological advancements that reflect already evident disruptions – for example, the replacement of typewriters by computers. Knott’s conclusion from her in-depth research is that companies are experiencing less growth from R&D efforts because they are worse at innovating, not because innovation has gotten harder.

But it’s not all doom and gloom. What Knott identified using RQ is that companies aren’t necessarily fated when an industry declines or is disrupted; they often find opportunities elsewhere by diversifying.

Knott claims that “if the top 20 firms traded on U.S. exchanges had optimized their 2010 R&D spending using the RQ method, the collective increase in market cap would have been an astonishing $1 trillion.”

Part of that optimization uses RQ to leverage the potential longer-term benefits. According to Knott, “RQ also allows companies to link changes in R&D strategy, practices, and processes more closely to profitability and value.”

Allocating Resources to Core, Adjacent, and Transformational Initiatives

Nagji and Tuff, referenced above, offer solutions on better optimizing R&D portfolios. The team conducted research on the industrial, technology, and consumer goods sectors that showed a pattern whereby the allocation of resources across core, adjacent, and transformational initiatives correlated with significantly better performance that was reflected in a firm’s share price.

According to Nagji and Tuff, “companies that allocated about 70 percent of their innovation activity to core initiatives, 20 percent to adjacent ones, and 10 percent to transformational ones outperformed their peers, typically realizing a P/E premium of 10 percent to 20 percent.”

While each company will look for a different balance depending on their risk profile, the authors stated that Google strives for a 70-20-10 balance and estimates that the 10 percent allocated to transformational efforts are responsible for the company’s new offerings.

Nagji and Tuff state that a company that seeks to catch up with industry leaders might choose a more risky, transformational portfolio. A company that is already dominant may decide to reduce its risk and concentrate on core initiatives, not transformational ones.

M&A and Acquiring as a New Form of R&D

The trend in M&A of acquiring high-tech startups has become a popular strategy for supplementing or mimicing traditional R&D.

According to the Foundation, the number of technology-based startups in the U.S. economy grew almost 50 percent in the last ten years. Moreover, VC-backed startups grew employment and sales 40 percent faster than non-VC-backed startups on

A panel of venture startup founders including Garrett discussed corporate innovation and investment with Paresh Dave of the LA Times. According to Matt Garratt of Salesforce, it’s not just tech companies that are involved. Of the total number of tech acquisitions in 2016, Garratt says “around half were from non-tech buyers.”

The panelists noted that corporates who do invest and acquire tech startups are unfamiliar with the process and concepts such as “deal flow, diversifying bets, and portfolio company growth.”

We’ve built content detailing acquihires and technology acquisitions. Learn more about how M&A is being used to drive growth in our article “Why Pursue an M&A Strategy? Explore the Motivations Behind Deals and Best Practices to Help Them Succeed”

Best Practices for R&D

Based on Nahji and Tuff’s research and a case study analysis of Amazon and Google outlined in the previous article, “Research and Development – Who Does it Well and How,” we summarize some best practices of these market leaders.

- Articulate a clear R&D ambition (Nagji and Tuff, 2012).

- Balance core and transformational ventures (Nagji and Tuff, 2012).

- Use technology throughout an organization, not just as part of partitioned R&D activities (Bezos, 1997).

- Recognize core competencies and maximize them (Bezos, 1997).

- Balance risk and potential breakthrough goals with investor and stakeholder tolerance (Nagji and Tuff, 2012).

- Develop a cut-throat portfolio selection strategy (Google X, 2016).

This dive into the R&D landscape has highlighted some best practices that companies can use toward a better strategy for their R&D efforts. Whether the decision is to pursue transformational innovation and the next breakthrough or to focus on broad learning through acquiring or strategic M&As, we hope we’ve offered some valuable data and insights. Below are additional resources that can supplement our R&D compendium.